CIFC Viewpoint

There has been much written recently concerning the topic of CLOs. Many of these writings are bearish with some even predicting financial Armageddon. Some articles possess certain truths while many are uninformed and do not. Some compare CLOs to the much-demonized Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO), which bear some responsibility for the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) – spoiler alert: CLOs are not CDOs. Countless articles contain inadequate perspective, flawed assumptions and/ or, employ selective facts or are written by those who have limited life or financial markets experience. A myriad of these articles include massive numbers that are designed to elicit a reaction. As Brian Chappatta recently observed in a Bloomberg opinion piece on the CLO bogeyman, “Never trust absolute dollar figures, no matter how large they may seem.”1 Emotion and opinion are ubiquitous, while facts and analysis are scarce.

Don’t blame the pundits, journalists or the “experts”. It is human nature to seek the accolades, tributes and treasure associated with identifying catastrophe. However, the “experts” are notoriously lousy at predictions of doom. As I regularly remind clients: If I could predict the future, I would be self-employed. It is also an unfortunate reality that it is unfashionable these days to be anything other than bearish on many topics. Readers beware and remember the words attributed to Mark Twain: “If you don’t read the newspaper you are uninformed, if you do read the newspaper you are misinformed.”

What is a Bank?

In a probable attempt to impress or obfuscate when explaining CLOs, many “experts” will use acronyms, figures, generalizations and/or terminology that can make the eyes water with boredom and the brain spin with confusion. Perceived complexity is a breeding ground for unfamiliarity bias and predictions of disaster. To simplify the matter, let’s begin with a basic commercial framework of lending to provide some perspective.

Most of us are familiar with Bank of America, Citibank, JPMorgan and other large banks. What do banks do for a living? In simple terms, what is the business model of banking and how does a bank create their balance sheet and derive their income?

To fund their operations, banks frequently issue debt and equity securities in the capital markets. Investors will participate in the offerings that best fit their investment risk, return and liquidity objectives. Banks also enjoy large amounts of deposits, some of which are insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Depositor capital is a very short dated obligation given the ability of savers to access their money at any given time. Notwithstanding, the banks utilize this capital to carry out their business, particularly term-lending to businesses and consumers. At the end of the day, banks lend long and borrow short. Banks earn a spread from deploying their shorter dated capital into longer dated lending activities. This is how banks earn income. This approach mostly eliminates interest rate risk but exposes a bank to liquidity risk. Obviously, capital and lending are the lifeblood of an economy, so this activity is vital.

To support their lending activities, banks have very involved processes and infrastructure to underwrite credit and monitor risk. Credit risk is another component of the banking model and can be defined as the sum of defaults multiplied by losses. The product of this calculation is known as “credit costs” and is a common way to think about the risk/reward equation when lending money. This is the “risky” part of making loans and another component of the spread renumeration that banks receive for making them. Banks and various financial institutions are all exposed to these probable losses. For the unversed, it is important to know that defaults are not losses and that part of the banking model is to minimize these likely costs.

In summary, a bank borrows money, lends that money, generates income and incurs credit costs against this revenue. The bank then takes its “net” income and pays depositors, creditors and employees. The remainder is what shareholders earn, commonly referred to as Return on Equity. This may be an oversimplified explanation; nonetheless, it is the essence of the banking business model.

What is a CLO?

Like a bank, a CLO is an actively managed entity that issues debt and equity securities into the capital markets and then deploys that capital into a pool of senior secured loans. The debt and equity investors in CLO securities are not dissimilar from bank debt and equity investors. They too are making investment decisions based on their risk, return and liquidity needs. Investors in CLOs can invest in the very top of its capital stack by buying AAA rated bonds all the way down to the unrated equity of a CLO as losses from defaults are not distributed equally, just like in the real world. From a commercial standpoint the CLO manager, like a bank, borrows money, lends that money, generates income and incurs credit costs. The CLO manager then takes the “net” income and pays its creditors and employees. The remainder is distributed to their equity investors and is also known as Return on Equity. Hence, if you are acquainted with the fundamentals of the banking business model, you are already familiar with the basic business model of CLOs. In fact, a CLO can be viewed as a bank that does not accept deposits and has a defined start and end date.

From a sourcing perspective, there is a nuance. CLO managers gather their loans like bond managers gather bonds, purchasing them in the new issue or secondary market from commercial or investment banks who arrange these financings on behalf of corporate issuers. There are other key differences between banks and CLOs as well. One important distinction is match funding. Whereas a bank lends long and borrows short, a CLO lends long AND borrows long. The CLO business model, unlike the bank business model, is not exposed to liquidity risk. You don’t read about that in the newspapers…

Snapshot of Senior Secured Loan Issuers3

With respect to the day to day business of a CLO manager, the activities look very similar to those of commercial banks in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, before the banks began to get regulated out of the lending business. In fact, many CLO managers are staffed with ex-bankers who have decades of credit and lending experience. CLOs also have underwriting and risk management processes and infrastructure that look like banks.

Why Do CLOs Exist?

There are many reasons why CLOs exist. Though, a core origin is a direct result of regulatory changes over the past two decades. Regulators do not want banks using depositor capital to make risky loans and, importantly, they do not want to step in to rescue the big banks again, particularly after the experiences of the GFC. This makes sense when you think about the perverse incentives that FDIC insurance could provide an unscrupulous bank lending officer. Yet capital and lending, being the lifeblood of any economy, need to flow to create jobs and economic growth.

Regulators realize this reality.

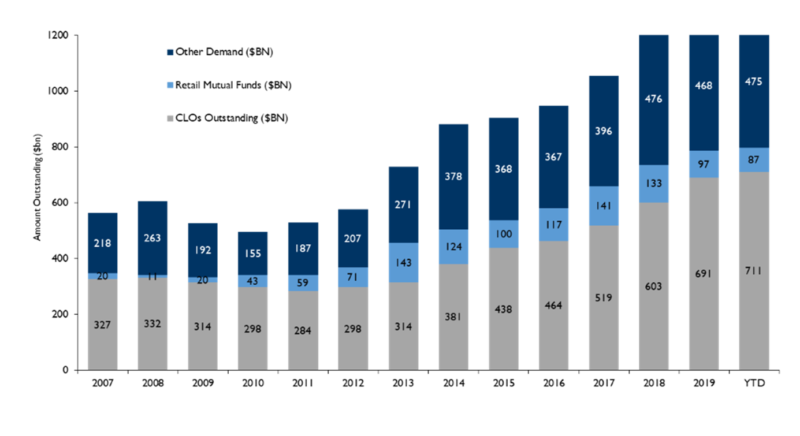

Today, most of the capital being provided in the $1.2 trillion senior secured corporate loan market is from non-banks who invest via CLOs, separately managed accounts, institutional and retail mutual funds and even directly.4 These investors include pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, endowments & foundations, insurance companies, family offices and retail investors, among others. Banks remain large originators of loans but are the minority of the end investor base today given the current regulatory and commercial environment. This is by design. Non-bank investors have lower capital costs, unburdened balance sheets, de minimis brick and mortar infrastructure expenses and, there is a view, they are more adept at pricing and managing credit risk. Furthermore, CLOS are not conflicted by the desire to win other banking business away from lending money.

Loan Holder Base Breakdown4

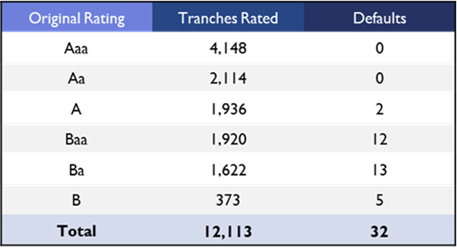

As the banks have been regulated out of the lending business, they have evolved to become large investors in the highest rated investment grade CLO securities. This correspondingly makes sense given the “lend long and borrow short” model, need for rate insensitive income and familiarity with lending operations. Moreover, AAA rated CLO securities are structured to insulate investors from severe default scenarios. In fact, of the 6,000+ Aaa and Aa CLO tranches trackeby Moody’s since 1993, not one has ever defaulted.5 This is one of the data points regularly overlooked by the “experts”…

U.S. CLOs Defaults by Original Rating (1993 – 2019)5

Could this change in the future? Possibly but most probably this is an unlikely outcome. If this improbable scenario were to occur, the problems in the world would be sweeping and inordinate and most other asset classes would look like dust. It should also not be lost on the “experts” that banks do extensive due diligence on the CLO managers in which they invest and that CLOs today are better capitalized and have less leverage than in pre-GFC days. Details…

One additional observation. Many “experts”, incorrectly, continue to accept as truth that CLOs, which invest in loans to companies through rigorous underwriting methods, are the cousins of CDOs, which were primarily invested in subprime mortgage loans. “Experts” should recognize that a CLO is designed to complete a thorough credit underwriting process associated with every investment made, just like a bank. Each borrower is identifiable and analyzed with complete transparency surrounding its financial condition. CLO portfolios are independently constructed, actively risk managed and subject to forced diversification through their indentures and thus avoid concentration risk. This is unlike a CDO, which generally amalgamates debt, for which little is known or could be known about the individual entity, whether they are a truly qualitied borrower, lied on their application or their ongoing quality. Additionally, the companies in which CLOs invest provide financial updates and are held to certain standards unlike a subprime mortgage borrower for which only a snapshot of credit health was taken upon the creation of the loan. Details (again)…

There are many other considerations that influence the management of CLOs including diversification requirements, limitations on CCC-rated risk and other lower quality assets, overcollateralization conditions, a slew of risk tests necessitated by the rating agencies and structures that provide for the delevering of the entity when and if risk does deteriorate. Ultimately, CLOs commercially look, lend and act like the banks of yore. CLOs likewise serve a vital function in the economy.

Conclusion

Our purpose in writing this piece was to provide perspective and hopefully we were successful in this endeavor. There are numerous other supplementary points that we can leave for the future, including a multi-decade history and evolution of the loan market, CLO indentures, the role of rating agencies and regulators and a thorough overview of the motivations of CLO investors. In the interim, we hope this introduction has brought some clarity and balance to the Armageddon debate.

- Source: Bloomberg, “CLOs Are Not CDOs, Not Even During a Pandemic”. 16 June 2020

- For illustrative purposes only

- The logos used in this presentation are the property of their respective owners. These images have been copied from publicly available sources on the internet and prior permission was not received from the owners or otherwise. Use of these logos is for illustrative purposes only.

- Source J.P. Morgan data as of June 30, 2020.

- Source: Moody’s Investors Service, data as of December 31, 2019.

Important Information:

The information contained herein (the “Information”) is being furnished solely for informational purposes for use by you in preliminary discussions with CIFC. In particular, the Information is not, and is not intended to be, an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to purchase, any securities or any other interest in CIFC or in any fund, account or other investment product or assets managed by CIFC or to offer any services. Any such offering and sale would be made only on the basis of certain transaction documents and, as the case may be, a final offering circular and related governing and subscription documents (together, “Transaction Documents”) pertaining to such offering and sale and is qualified in all respects and in its entirety by any such final Transaction Documents. In the event of a conflict between this Information and the Transaction Documents, the Transaction Documents prevail.

The Information is preliminary, subject to change at any time and is not, and should not be assumed to be, complete or to constitute all the information necessary to adequately make an investment decision. We have no obligation to update any or all of the Information or to advise you of any changes, and no representation is made as to the accuracy or completeness of the Information set forth herein. The distribution of this communication and any files transmitted with it in certain jurisdictions may be restricted by law.

The Information is provided to you on the understanding that, as a sophisticated institutional investor, you will understand and accept its inherent limitations, will not rely on it in making any decision to invest with CIFC or in any fund, account or other investment product managed by CIFC, and will use it only for the purpose of preliminary discussions with CIFC. In making any investment decision, you should conduct, and must rely on, your own investigation and analysis of the data and descriptions set forth in the Information, including the merits and risks involved.

Any reproduction or distribution of this Information, in whole or in part, or the disclosure of the contents hereof, without the prior written consent of CIFC, is prohibited. By retaining the Information, you acknowledge and represent to CIFC that you have read, understood and accept the terms of this Information. You hereby agree to return to CIFC or destroy this Information promptly upon request.

For information regarding our privacy policy and procedures, please visit http://www.cifc.com/privacy-statement/.