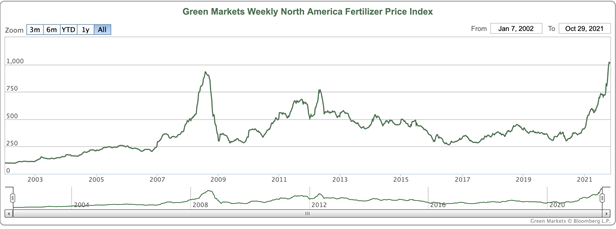

Last year around this time, fertilizer prices were approaching their lowest levels in a decade. Fast forward 12 months, and fertilizer prices are now at decade highs, increasing to levels last seen in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Distressingly, unlike some of the other pandemic-driven hiccups in commodity markets like lumber and uranium, which saw prices spike sharply before resolving to more rational levels, there are concerns that fertilizer prices are being driven by potential supply shortages. In other words: this isn’t just a quick little COVID-19 reopening bubble, but rather a price spike driven by fundamentals that are “unlikely to correct quickly.”

Source: https://fertilizerpricing.com/priceindex/

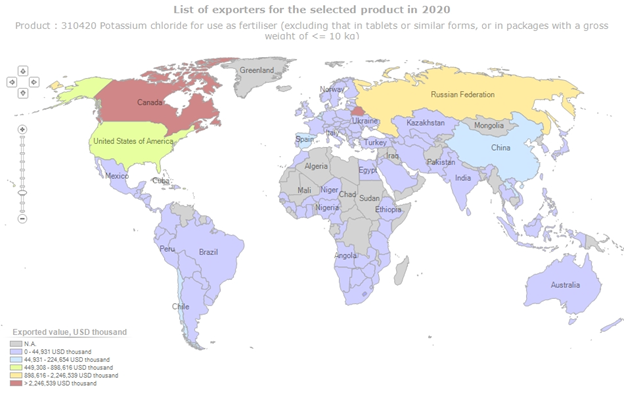

The Green Markets Weekly North America Fertilizer Price Index (above) tells the tale. The index is composed of three fertilizer benchmark prices: U.S. Gulf Coast Urea, U.S. Cornbelt Potash, and NOLA Barge DAP. The fertilizer price hike, however, is not primarily a U.S. problem. This is a global issue, with the potential for massive geopolitical consequences. At the end of September, China banned the export of phosphates until at least June 2022. That’s a big deal, seeing as China’s is the world’s top exporter of phosphate. According to Statistics Canada’s Farm Input Price Index, fertilizer costs for Canadian farmers are at their highest since Q2 2015, spiking almost 20 percent in the last two months. In Brazil, which was the world’s largest exporter of soybeans and third largest exporter of maize in 2020, President Jair Bolsonaro is warning of fertilizer shortfalls next year.

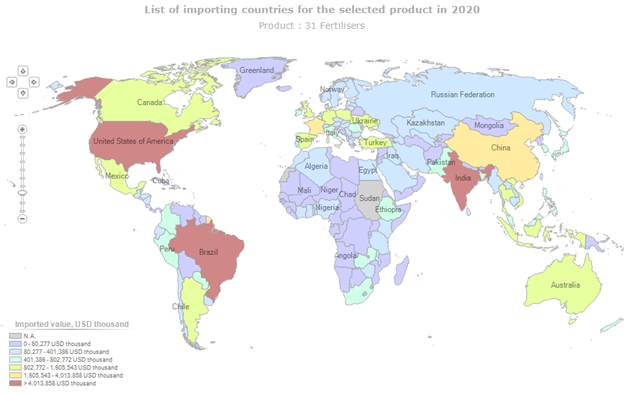

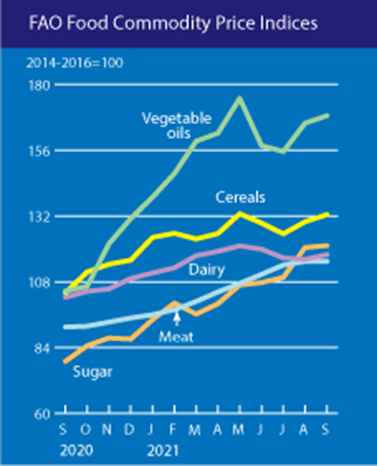

Map of global imports of fertilizer by country

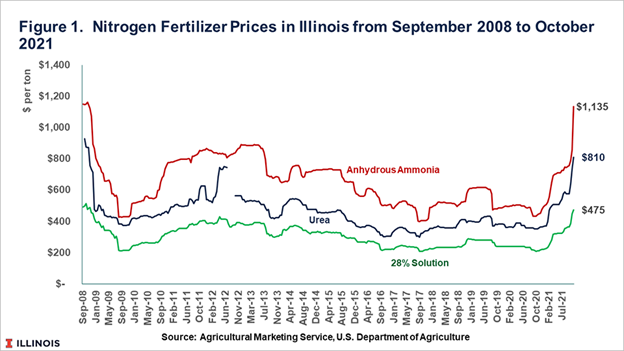

“Fertilizer,” of course, is not a single commodity. All fertilizers come in different strengths and blends, but in general, the three major nutrients are nitrogen, phosphate, and potash. Nutrient requirements vary by crop. Corn, for instance, is a nitrogen intensive crop. High prices of nitrogen-heavy fertilizers, for example, may cause farmers to rethink what they will plant next season. Those with sufficient capital and courage may wager that higher corn prices will compensate for upfront costs – indeed, global maize prices are up 38 percent year-on-year according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). If too many farmers ditch corn for soy, however, it is possible that a market imbalance could lead to lower soybean prices and even high corn prices.

Analyzing the supply chains for fertilizer production is not well-suited for those with coronary issues. Morocco, for instance, holds 72 percent of all phosphate-rock reserves in the world. Much of those reserves are in the Western Sahara, which wants independence from Morocco and has recently threatened attacks against Moroccan security forces if it isn’t granted authority to hold a self-determination vote. Algeria supports Western Saharan independence – and just halted natural gas exports to Spain via Morocco this weekend. (Spain gets half of its natural gas from Algeria, in case you were wondering.) Or take potash – whose second largest exporter in 2020 was Belarus. Yes, the same Belarus governed by dictator Alexander Lukashenko, who thinks COVID can be cured with vodka and tractors.

So why is all this happening now? As always, a combination of factors is the culprit. For one thing, Hurricane Ida shut down anhydrous ammonia plants in Louisiana. At the global level, however, the single biggest driver of higher fertilizer prices has been the spike in global natural gas prices. Natural gas is critical for the production for ammonia, and in Europe, for example, ammonia prices are four to give times higher than normal. That adds up considering ammonia makes up 80 percent of the cost to produce nitrogen-fertilizer. We briefly touched on this in our own piece on the spike in natural gas prices back in September. Add in higher corn prices (leading to more corn planting and therefore more demand for nitrogen fertilizers) and the general state of global supply chains, and the picture becomes clearer.

The question, of course, is where fertilizer prices go from here. The CEO of Archer-Daniels-Midland Company said he wasn’t concerned about fertilizer supply issues yet, but rather that fertilizers will continue “to be available for farmers only at higher prices.” That tracks with FAO projections, which indicate sufficient overall supply of nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium for fertilizer use up to 2022. Then again, the FAO also says its forecasts to not account for “raw material limitations, logistical problems, unscheduled shut downs, and natural calamities,” or in other words, for everything that has happened in global fertilizer markets in the last 12 months. Meanwhile, China’s impulse toward protectionism over fertilizer exports could easily lead to a domino effect of other export bans, which could drive prices still higher.

Times of crisis are also windows of opportunity. A crisis like the spike in fertilizer prices can lead to the adoption or prioritization of research or application of cutting-edge research, like plants bred to need less fertilizer. New technologies that can reduce the environmental effects of modern fertilizer production, or that can maintain (and even increase) crop yields will no doubt be in high demand in the years to come. The controlled release of fertilizers has already shown “very encouraging results” in this regard. The fertilizer price crisis could also spur adoption of wireless technologies, which can monitor field conditions in real time and use that data to economize on fertilizer usage. These will be critical areas of innovation to watch in the 2020s, and like so many things, the COVID-19 supply chain disruption may be accelerate the rate of discovery and adoption.

Source: https://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/foodpricesindex/en/

In the meantime, however, farmers around the world face hard decisions. The “good” news for farmers it that higher input prices for farming will translate into higher food prices. Many farmers have also already profited handsomely from 2021’s higher food prices, so the sticker-shock on fertilizer prices may be slightly easier to metabolize. Of course, that is dependent on favorable weather conditions among other uncontrollable variables, like global fertilizer supply, which as discussed above is far from certain. In addition, high food prices come with problems of their own. The so-called Arab Spring in 2010 and the subsequent rise of the Islamic State and the European migration crisis all started with a drought in Syria’s primary agricultural regions. Sky-high food prices in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis led to major global geopolitical dislocations, which in turn can lead to higher energy prices or cut off significant export markets.

What happens in fertilizer markets, in other words, won’t stay in fertilizer markets. This is ground-zero of the global economy, and cracks in the foundation will reverberate throughout the global economy in the form of risks and opportunities for those appropriately positioned.