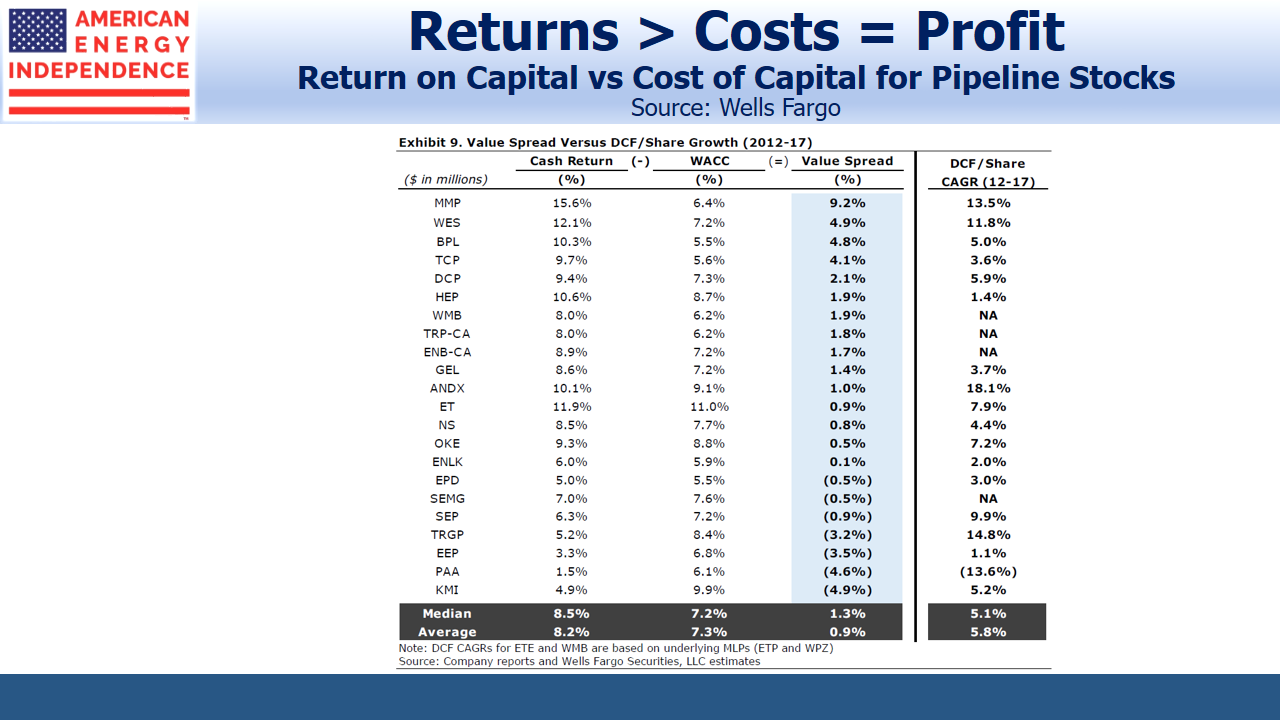

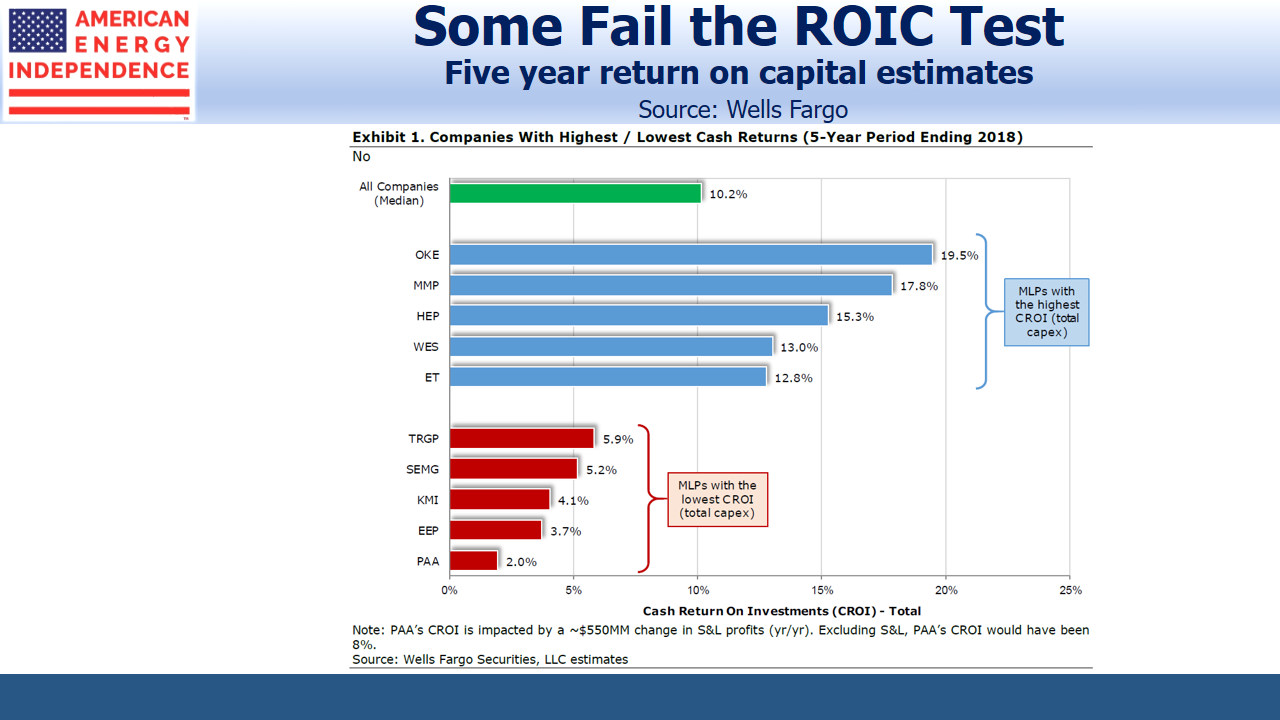

Last week’s blog (see Plain Talk, Fuzzy Math) showed how Plains All American (PAA) miscalculates its cost of equity capital. Equity is the key component in a company’s Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). In the presentation from their investor day, it was too low. We received several comments from readers and investors on the topic. The energy industry has been plagued with executives who value growth in assets over achieving an appropriate Return On Invested Capital (ROIC). Profits come from ensuring that a company’s assets earn a return higher than the cost of financing them, or that ROIC > WACC.

In one meeting with PAA, we asked if they’d considered selling themselves, since there’s a case that the company’s worth more in another’s hands. “Not yet ready to retire” was the answer. Financial discipline comes in many forms.

In too many cases, a CEO’s pay is directly linked to a company’s size. Per share operating metrics and capital efficiency ought to dominate. Management teams often strive for growth, which can conflict with an owner’s desire to earn a good return. Identifying companies where interests are more clearly aligned with investors is worthwhile.

Calculating ROIC for energy infrastructure businesses is tricky. Projects are funded over several years, and project-based returns are generally not disclosed. Therefore, some judgment is required. Wells Fargo made a serious attempt at calculating company-specific ROIC figures last year. A couple of companies (Enterprise Products and Plains) preferred their own methodology over that used by Wells Fargo, and their objections were duly noted in the research report. We explained in last week’s blog why we disagreed with PAA’s approach.

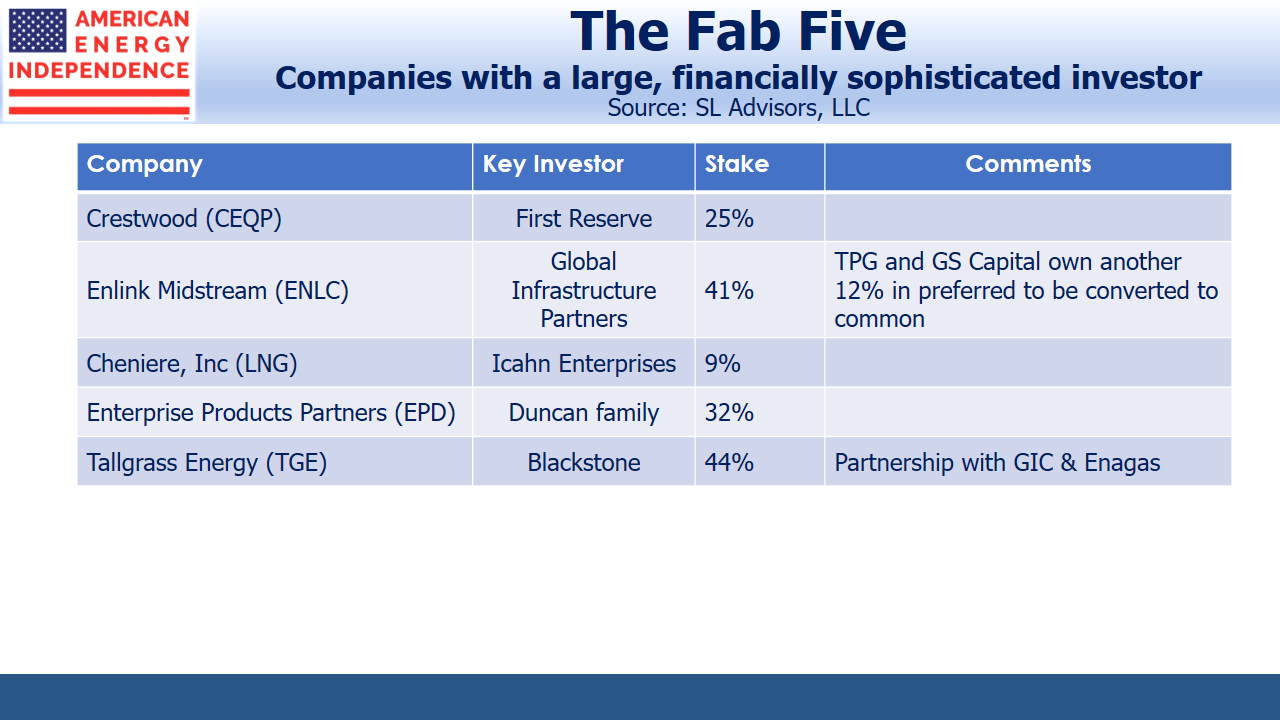

One solution to poor capital allocation decisions is to favor public companies with a significant private equity investor. At first this might seem odd. Private Equity (PE) has delivered mediocre results for investors (see a recent WSJ article, Private-Equity Firms Are Raising Bigger and Bigger Funds. They Often Don’t Deliver). The problem for PE investors is the ubiquitous “2 and 20” fee structure, which is a big drag on returns and has created some fabulous fortunes. However, most PE managers are financially more astute than the typical pipeline company finance department. The best apply rigorous financial analysis, and investing alongside them can be an attractive proposition.

Having a PE partner doesn’t guarantee good judgment, but it does assure that when such decisions are being made, there will be a voice demanding a profitable spread between ROIC versus WACC. Private equity is all about capital efficiency and achieving an attractive IRR. Many energy companies could benefit from greater financial discipline. A few already have such a partner, reflecting the more optimistic outlook PE investors have of the sector compared with public market valuations.

Blackstone and its affiliates own 44% of Tallgrass Energy (TGE). Investors in TGE are in effect co-investing alongside Blackstone, without having to pay Blackstone a fee. It’s appealing to all TGE holders to know that capital allocation decisions require Blackstone’s support.

Crestwood (CEQP) is a similar situation, with their private equity partner First Reserve, who own 25% of CEQP and has also invested in JVs with CEQP on mutually beneficial terms.

Activists can also play a constructive role. In 2016 Carl Icahn pushed Cheniere’s (LNG) CEO Charif Souki out of the company. That’s one solution to the principal-agent problem. Souki is a colorful character (see Coals to Newcastle), but Icahn disagreed with LNG’s investments in oil companies, which were not linked to their core business of exporting liquefied natural gas. In an interview with CNBC, Icahn explained why, and also vented his frustration with Souki’s compensation. The subsequent improved capital allocation and focus on executing their core business plan has seen LNG stock rise from $39 at the time of Icahn’s intervention to $66 today, without paying a dividend.

Enterprise Products Partners (EPD) has a well-regarded reputation for prudent management. Growth projects are funded internally. The Duncan family owns a third of the company and controls EPD, helping align shareholder interests with managements.

Global Infrastructure Partners recently invested in Enlink Midstream (ENLC), and currently owns 41%. Texas Pacific Group and Goldman together own 12% in preferred securities which are convertible into common equity. It’s too early to judge the impact of their ownership, but encouragingly ENLC’s CEO Mike Garberding was previously the CFO. We think it’s highly likely that capital discipline will become apparent at ENLC.

Significant equity ownership by management doesn’t always lead to good decisions. Rich Kinder continued to add to his already significant holding in Kinder Morgan (KMI), even as it lost two thirds of its value from 2015-16. KMI investors could have benefitted from an influential outsider. Energy Transfer (ET) is also heavily owned by management, but trades at a steep valuation discount because CEO Kelcy Warren has shown a willingness to exploit his investors if he can (see Will Energy Transfer Act with Integrity?).

Prior to their simplification, the significant insider ownership at Plains may have led the GP to place too much leverage at the MLP level, leading to unsustainable dividends at the MLP before consolidation. In some cases, management teams whose interests weren’t aligned with investors under the old GP-MLP model have not yet altered their behavior to acknowledge the alignment of interests that simplification brings.

The addition of PE investors makes creating value for all stockholders a higher priority. This requires disciplined capital allocation. While Rich Kinder, Kelcy Warren, and the insiders at Plains still own significant stakes, they are holdovers from a different model of wealth creation. Under their old structure, the GP directed the MLP’s activities while receiving preferential economics through Incentive Distribution Rights (IDRs). Growing the MLP increased IDRs even if it diluted returns for MLP investors.

Kinder’s simplification was almost five years ago, and yet their continued use of DCF and EBITDA in evaluating their Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) business betrays that they still haven’t updated their thinking. Depleting assets such as these reduce the return earned by equity holders, while the GP and his IDRs are largely immune. As a simplified, single entity KMI still hasn’t shown that it understands its long term ROIC for the EOR business.

Plains is using flawed math for capital allocation decisions. And, Kelcy may be back on the hunt for acquisitions to continue building his pipeline empire at ET.

The energy sector has been roundly criticized for overinvesting. Investors who favor companies where the rigor of PE analysis is applied to future projects could find that better capital allocation decisions follow. In our portfolios, we are biased towards companies likely to choose their investments wisely.

We invest in CEQP, ENCL, EPD, ET, LNG, KMI, TGE, PAA via Plains GP Holdings.

The post Pipelines Get Adult Supervision…Private Equity appeared first on SL-Advisors.