Bob Rubin was US Treasury Secretary from 1995-99 under Bill Clinton. Early in his tenure, the US$ came under severe downward pressure. Market pundits kept calling for the Treasury to provide US$ support, to stem the slide. This evoked memories of 1987, when a growing trade deficit caused persistent US$ weakness which pushed up bond yields and eventually led to the October stock market crash.

Relying on his almost three-decade career at Goldman Sachs which culminated in co-chairman, Rubin waited, allowing the US$ to continue falling. He recognized that even the US Treasury couldn’t stand in the way of the FX markets. He waited until the US$ sell-off paused, and then retraced for a couple of days, in the kind of move analysts call a “healthy correction.” Just as the small bounce is the US$ was testing the conviction of shorts, the Treasury launched a coordinated intervention with Japan, Germany, and Switzerland. The consequent trading losses inflicted on FX speculators took a while to heal, and traders were more cautious about shorting the US$ afterwards.

Today’s Federal Reserve does not possess such a deft hand. Perhaps it’s because the FOMC has to agree on policy, constraining them to decisions at their meetings rather than allowing chair Powell to act opportunistically. In any event, the Fed is missing the opportunity to begin an elegant exit from its $120BN monthly bond buying program. Surely the ten-year treasury note yielding 1.3% is proof of sufficient demand elsewhere and that the continued debt monetization is no longer needed.

If Bob Rubin was Fed chair, his planned exit from the Fed’s bond buying would be timed for when the market no longer needs it. Given a choice between tapering now, when yields are falling, or later when continued economic strength is driving yields higher, the former is clearly less disruptive.

But that’s not the FOMC’s game plan. Their strategy is to exit when they see full employment and 2% inflation expectations (or higher). We are to expect ample and timely communication, but they will nonetheless most likely be reducing their buying into a falling market. There’s probably no easy way to scale back over $1.4TN in annual bond buying, but the FOMC’s plan looks decidedly market-insensitive.

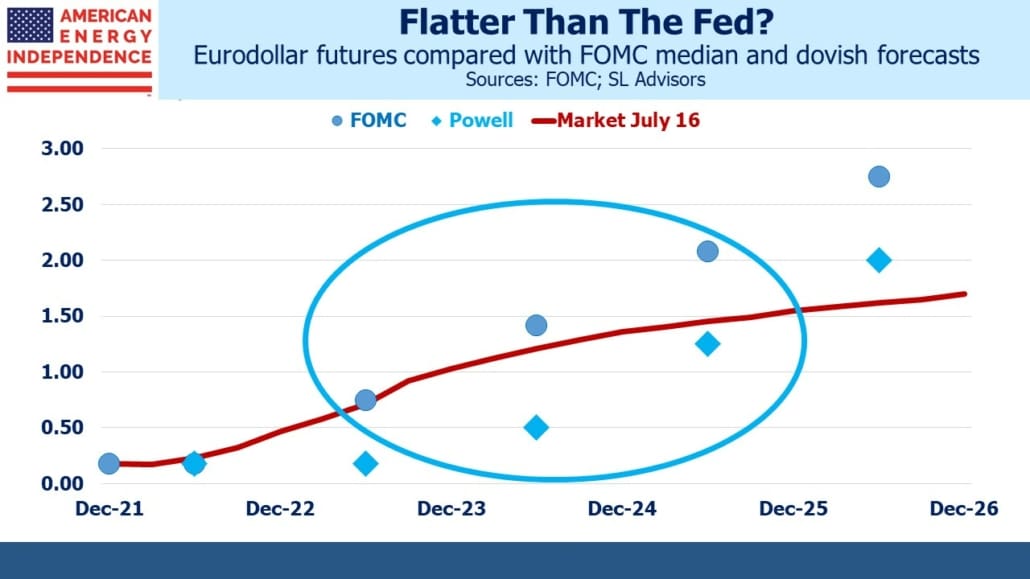

Eurodollar futures are priced for 0.75% of tightening by the end of 2023. The most dovish of the blue dots on the Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) expects policy to still be unchanged by then. Although the median is higher, the FOMC’s composition will likely become even more dovish over the next year (see Trading Futures With The Fed).

Jay Powell has promised that, if required,“… we will use our tools to guide inflation back down.” This is the bare minimum commitment of any Fed chair, and he’d clearly rather not have to. Powell is all-in on the belief that the inflation rise will be transient.

It may be, in which case the 1% yield on December 2023 eurodollar futures is too high. But if the FOMC is wrong, and inflation expectations become anchored well above 2% as a reasonable reaction to rising prices, the Fed will likely have to move more than just once a year, which is what’s now implied by the 52bps spread between Dec ‘23 and Dec’25 eurodollars.

It’s hard to envisage the type of economic environment by then that would justify the slothful monetary tightening currently priced into the market. It would likely require a persistent shortfall in employment, inflation back below 2% and little or no new fiscal stimulus, an unimaginable degree of Congressional restraint.

The SEP blue dots suggest a tightening pace of twice that.

The yield curve it too flat. It’s currently possible to bet with the Fed’s forecast of a very slow normalization of monetary conditions in a trade that should also work if it turns out they’re moving too slowly. It’s a way of betting with the Fed while having insurance in case circumstances move against them. The trade is to go long Dec ‘23 eurodollar futures and short Dec ‘25 futures, at a spread of 52 bps.

Inflation concerns are coming up regularly in conversations with investors. Wells Fargo recently calculated that 60% of the pipeline sector’s EBITDA is subject to tariff escalators linked to PPI, which is likely to exceed 5% this year. For liquids and NGL pipelines that could add up to a more than 3% increase in cashflows in 2022 – a benefit that requires no incremental capex, and is not just a one-time gain as it’ll become embedded into the tariff structure. We believe midstream energy infrastructure offers one of the most attractive ways to invest for inflation protection.

Finally, we liked a WSJ op-ed (see The Climate-Change Agenda Goes Out With a Bang) that noted the increasing pushback from voters around the world against the agenda of environmental extremists because of cost. Swiss voters have rejected an increased fuel tax; Britain’s cabinet is split over previously announced plans to ban gas-fired home heating; a proposed French diesel tax in 2018 helped create the “yellow jackets” protests. From Joe Biden on down, political leaders have downplayed the cost of the energy transition, instead of explaining that if something’s worth doing it’s worth paying for. Hopefully this will introduce a little more realism into policy debates.

We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that seeks to track its performance.

The post Market Underprices Rate Hike Risks appeared first on SL-Advisors.