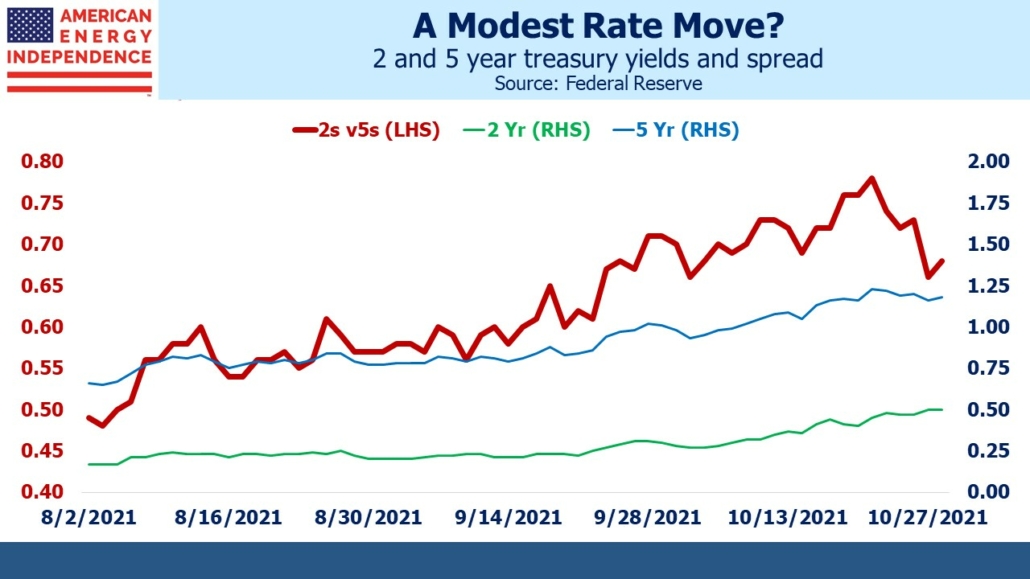

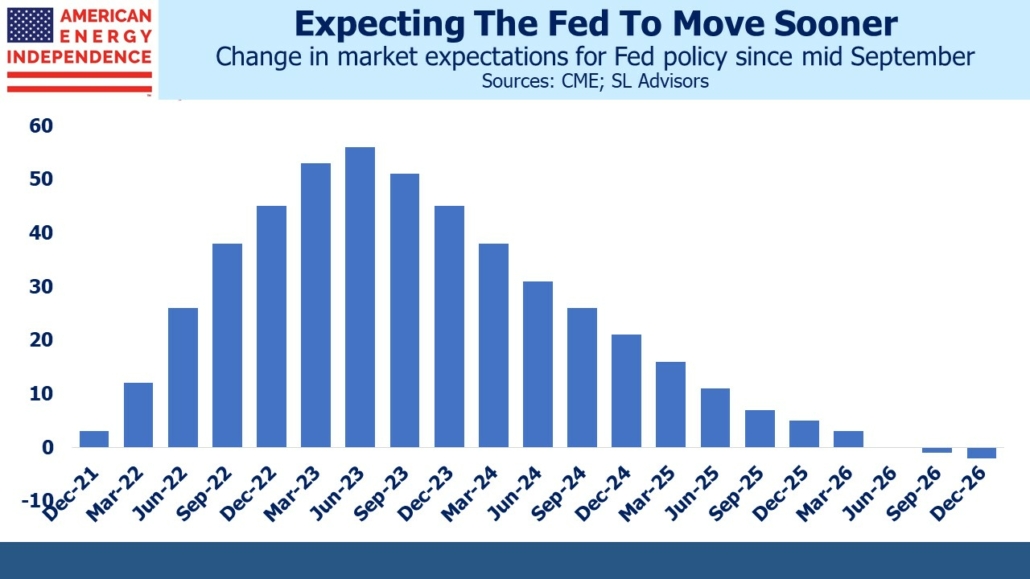

A significant interest rate move has taken place in recent days that has received scant coverage from mainstream financial media. The market has priced in a more aggressive pace of Fed tightening over the next couple of years, while simultaneously moderating the outlook beyond that. This flattening of the yield curve has been reflected in the spread between two and five year treasury securities, which reversed a steepening trend. The change in yields appears unremarkable. Eurodollar futures incorporate the same rate expectations but with greater precision, because they reflect market expectations of Fed monetary policy in three month increments.

Over just a few weeks, projected tightening of rates has been brought forward by at least a year. Ten year treasury yields have risen just a few basis point on the month, whereas eurodollar futures two years out have jumped 0.50%.

As a result, the trajectory of Fed policy has shifted even farther from guidance set out by the FOMC and many analysts.

For over a decade the Fed has sought to be more transparent about their decision making. This has included publishing minutes, holding regular press conferences and releasing projection materials on their economic outlook. The Fed’s projections have not always been accurate. The “dot plot” which sets out what FOMC members individually expect for short term rates has in the past been revised to match those reflected in the yield curve.

The Fed’s “neutral” rate is the level of Fed Funds at which they’re not seeking to provide stimulus or restraint. For many years it was 1-2% above long term bond yields, even though they should theoretically be similar (see Bond Investors Agree With the Fed…For Now). The two finally converged in 2018, mostly via the Fed consistently revising their figure down. The discrepancy returned after Covid and still exists today to a lesser degree.

The central bank’s past failure to correctly forecast its own actions is a source of amusement for those who pore over such minutia. Fed chair Jay Powell has said in the past that forecasters have much to be humble about, an observation most applicable to the FOMC.

So it’s not the first time the market and FOMC have disagreed. Based on history you’d have to favor the collective wisdom of millions of investors over the Fed, even though the latter makes the decisions. Nonetheless, futures prices now anticipate short term rates 0.65% higher by the end of next year. As recently as late September, nine of 18 FOMC members thought monetary policy would still be unchanged at that time.

The Fed continues to buy $120BN of bonds per month. Next week they’re expected to announce tapering, and past comments have suggested a measured reduction of $15BN per month which would take until June 2022 to complete. They won’t tighten while they’re still buying bonds, which would mean no sooner than 2H22. Market forecasts of earlier tightening rely on faster tapering or a series of rapid moves as soon as July.

Either scenario is at odds with an FOMC whose public comments maintain inflation is transitory and that the employment situation still needs improvement. Interest rate futures are priced for Jay Powell to express less confidence in the “transitory” narrative around inflation.

Wednesday’s press conference following the FOMC’s two-day meeting should resolve the discrepancy for now. If Jay Powell confirms market forecasts, that will represent a concession that earlier confidence on moderating inflation was misplaced. If he sticks with his theme, at least some of the recent curve flattening will reverse.

Recent data has been mixed. US 3Q GDP rose just 2%, held back by the delta virus in some states and continued supply difficulties. Apple’s earnings on Thursday were a case in point. But the Employment Cost Index rose 1.3% over the prior quarter, up 3.7% over the past year. Healthy wage growth suggests strong employment

Total employment of 147 million remains five million below pre-covid levels, a metric Powell has often cited as evidence that the employment component of their mandate remains unfulfilled. Nonetheless, record high job openings noted in last Sunday’s blog post (see Life Without The Bond Vigilantes) suggests demand for workers is being frustrated by a skills or location mismatch.

Rising energy prices are a predictable part of the energy transition (see Is The Energy Transition Inflationary?), even if progressives whose policies have constrained oil and gas supply won’t claim credit. Tighter monetary policy isn’t much help for consumers paying more to fill up their cars and heat their homes. The COP26 climate change meeting is well timed to grapple with the challenges unrealistic climate extremist energy policies have created.

The real issue is that consumption is running well ahead of trend, because the fiscal and monetary response to Covid was disproportionate. That could justify tighter policy, but isn’t a reason that’s received much attention.

A few central banks have already begun to withdraw stimulus. Canada abruptly stopped their bond buying last week. The UK’s Bank of England has said they may consider raising rates. Short term rates in Brazil have reached 7%.

Last week the European Central Bank (ECB) maintained their large bond buying program, and ECB President Lagarde said markets were incorrectly pricing in a tightening next year. Traders were non-plussed, and yields rose further. The Fed and the ECB are the two heavyweights not yet willing to abandon the transitory narrative.

Some commentators suggest that stubbornly elevated inflation may force central bankers to concede to the market’s forecast of higher rates, sooner. But the bond market has lost its ability to cower policymakers into submission. Persistently low bond yields and record high stock prices suggest that the Fed has plenty of time to continue their single-minded pursuit of maximum employment.

Next week’s Fed press conference and the conclusion of COP26 will provide important guidance for investors in bonds and energy.

The post How Will Fed Chair Powell Respond To The Market? appeared first on SL-Advisors.