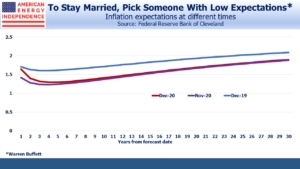

The biggest question for long term investors is why bond yields remain so low. The Equity Risk Premium (see Stocks Are Still A Better Bet Than Bonds) has favored equities for most of the time since the 2008 financial crisis. Inflation expectations remain well-anchored and are noticeably lower than a year ago. Investors don’t expect it will even rise to the Fed’s 2% target within the next three decades, despite the Fed’s professed objective to overshoot this.

Should inflation, and therefore interest rates, move surprisingly higher, a key support for the bull market would be knocked away.

Betting on higher inflation, or even worrying about it, has been a wasted effort for as long as any of us can remember. My own career began in 1980, around the time inflation peaked. Bond yields have been falling ever since. Jim Grant’s Interest Rate Observer has been warning of resurgent inflation for this entire period. That he retains so many subscribers shows how erudite prose beats accurate forecasts.

The most likely outcome remains low inflation. However, it’s safe to say that few investors are prepared for a surprise. Should it happen, the resulting market response is likely to be traumatic.

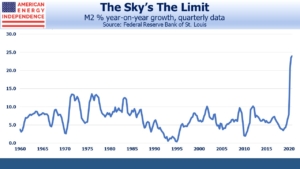

There are reasons to worry. M2 is rising faster than at any time in the past 50 years, exceeding even the inflationary late 70’s and early 80’s. The link between money supply and inflation appears to have broken, and any analysis of current conditions must consider that Covid has affected everything. Nonetheless, 24% year-on-year growth means something.

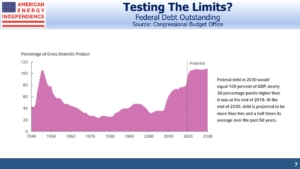

The Federal deficit, invariably nowadays the subject of hand–wringing but inaction, is forecast to be $3.3TN this year, at 16% of GDP the highest since 1945. The Congressional Budget Office expects total debt outstanding to reach 109% of GDP by 2030, exceeding the 1945 peak at the end of World War II. Unlike then, it is expected to remain at elevated levels.

Fiscal discipline has gone because there are few votes to be had in it. Past and present fiscal profligacy has caused little visible damage, as measured by the bond market. The burden of proof increasingly lies with the advocates of prudence.

Believers in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) should be pleased. MMT holds that countries with a fiat currency, the prevailing global standard nowadays, can never go bankrupt. This is because the government can always issue itself money to pay any bill. Therefore, deficits don’t matter, as explained by Stephanie Kelton in The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy (you can read our review here). Or at least, deficits don’t matter until excessive government spending leads the economy to exceed its productive capacity, which is inflationary.

MMT remains at the fringes of political discourse, embraced by the same progressive Democrats who love the Green New Deal (see The Bovine Green Dream). It’s not conventional economic policy.

And yet, the deficit trend suggests that we are embarking on a great MMT experiment. $1TN is now a round lot for stimulus spending, rebuilding our creaking infrastructure, forgiving student debt or combating climate change. Proposing less betrays a lack of urgency. Derisively low bond yields deny fiscal conservatives their most potent weapon. MMT advocates must retain a disciplined silence, in case the rest of us comprehend that we are unwittingly doing their bidding.

Years of costless Federal profligacy have caused voters to become so disinterested in budget discipline that inflation is the only remaining constraint. We will continue testing the limits until we get a different result. MMT has become our fiscal policy. Higher inflation is assured, eventually. We don’t know when, but until then fiscal hawks will remain defenseless, disarmed of empirical arguments.

Therefore, every investor needs to consider how their portfolio will cope with higher inflation. Though the timing of such is unclear, it is inevitable. Gold and Bitcoin suggest that some see warning signs ahead.

The point of investing is to preserve purchasing power. For years, simply earning positive returns was almost sufficient. Companies with pricing power offer some protection. If inflation is 5%, Coca-Cola will pass that through to customers, like so many companies with a strong brand and barriers to entry.

Real assets are another good choice. The rising cost of pipeline inputs (steel, concrete, labor) will increase the value of what’s already built. The next few years will in any case see few new pipelines. President Biden and relentless legal challenges from environmental extremists will add value to existing assets that have become hard to replicate.

This is why planned spending on new pipelines is continuing its downtrend. Investors are welcoming the resulting boost to free cash flow, which has spurred a series of buyback announcements (see Pipeline Buybacks To Shift Fund Flows).

Oil is a global commodity whose recent price rise is partly to compensate for a weakening US dollar. Natural gas is similar, although relatively high transportation costs allow greater regional price disparities. And much of the North American pipeline network operates with tariffs that include inflation adjustments.

Inflation remains dormant, but America is probing for the conditions which will change that. MMT proponents are getting their wish. Pipelines offer protection for every portfolio.

We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that seeks to track its performance.

The post Deficit Spending May Yet Cause Inflation appeared first on SL-Advisors.