In Gretchen Bakke’s interesting book ‘The Grid,’ she states that; “The grid is not just something we built, but something that grew with America, changes as our values changed, and gained its form as we developed as a nation. It is a machine, an infrastructure, a cultural artifact, a set of business practices, and an ecology. Its tendrils touch us all.” Andre Anderson, the CIO of Energy Trading at The Strategic Funds, has spent over a decade working in diverse roles across the power industry, which provides Andre with an edge as an investor in the space. As Anderson puts it, “When facing uncertainty – be it weather or technology driven change, it helps to come prepared and with an understanding of the ‘plumbing’ of the system you are looking to navigate, that way you can consistently harness opportunities as they begin to form on the horizon.”

Below we share an overview of some of the dynamics at play in these markets and offer some of Anderson’s unique perspective in order for investors to better understand the potential risks and opportunities.

Electricity is an unorthodox commodity. Technically, of course, electricity is a fungible economic unit. One megawatt can be replaced with another megawatt – it doesn’t matter whether the electricity in question is generated from a nuclear plant, from a solar panel, or natural gas. Like most commodities, electricity is traded in markets and in just about any quantity.

Electricity, however, is not like all other commodities. “Electricity is the only commodity you can’t store,” says Anderson. Coal, natural gas, oil, solar panels, wind farms, nuclear plants – these are all just means to an end, a way to store the capacity to generate electricity whenever it is needed, whether to power a hospital’s emergency equipment or to ensure I can tweet my brilliant thoughts to the universe on-demand. In a literal sense, all energy commodities are an attempt to store lightning in a bottle. “We live in the flicker” – as long as the old electric grid keeps rolling.

Not only is it impossible to store electricity – but modern life screeches to a halt if electricity is not immediately available whenever an individual household wants to flip a light switch, or the Port of Los Angeles heeds President Biden’s pleas to operate 24/7 to resolve supply chain woes (a topic for another time). Indeed, the constantly reliable availability of electricity has become a marker of a society’s relative civilization, and in that sense, electricity shares characteristics in common with water. Water has little to no value in exchange – that is, until water becomes scarce, at which point, there is no price a desperate human won’t pay to acquire it.

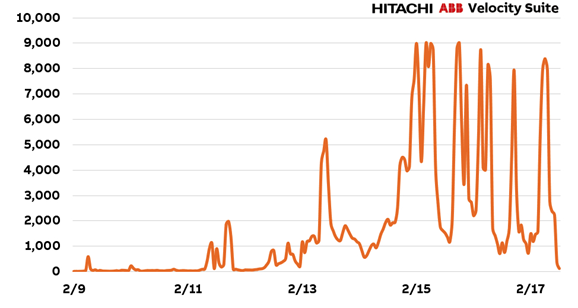

The same is true of electricity – it is taken for granted until it isn’t available anymore, at which point, prices tend to surge at rates defying the logic of even the most volatile commodity markets. COVID-19 has exacerbated this dependency. Anderson notes that the normal “9-5 office job has been replaced with the work from culture, resulting in a shift of electricity consumption from wholesale to more residential, creating new congestion and demand patterns.” Case in point: During a winter storm in Texas this last February, the cost of electricity surged from $.09 per kilowatt hour to $9.00 – and only stopped there because Texas’s Public Utility Commission prevented the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) from going any higher.

ERCOT real-time average hourly electricity prices, Feb. 9-17, 2021, $/MWh

Source: Hitachi ABB Power Grids, https://www.powermag.com/great-winter-storm-of-2021-will-live-in-grid-history/

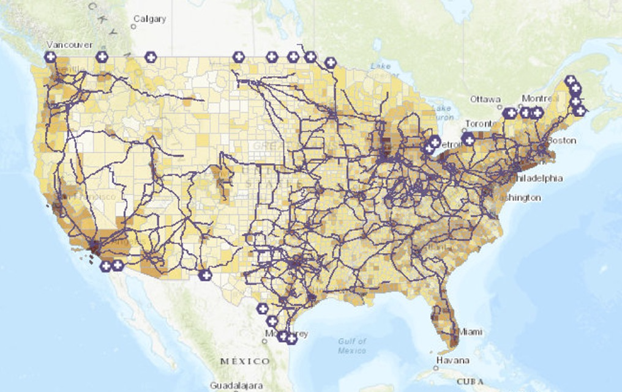

In addition, the electricity market in the U.S. is much more fragmented compared to most other markets. Much, though not all, of the U.S. power grid are covered by Independent System Operators (ISO), some of which, like ERCOT, only cover a single state, while others, like the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO), cover an entire region. Just last week, the Southeast Energy Exchange Market received clearance from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission for a new proposed trading platform. The job of ISOs is to operate the transmission system independently and encourage competition for electricity generation among wholesale market participants. Each ISO has different rules and regulations, however, making them difficult to navigate and erecting a high barrier of entry to most investors.

Electric Power Markets, National Overview

Source: https://www.ferc.gov/electric-power-markets

The U.S. electric grid is a complicated network of substations, transformers, and powerlines that link energy producers to consumers. The U.S. electric grid is a modern marvel – but it has also fallen into disrepair. Joshua Rhodes, a postdoctoral research at the University of Texas at Austin, has estimated it would take trillions of dollars just to maintain the current system. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, much of the U.S. electricity grid is aging, with as much as 70 percent of transmission and distribution systems “well into the second half of their lifespans.” This is a patchwork network of hundreds of thousands of transmission lines, as well as local distribution lines that operate in varied federal, state, tribal, and local regulatory jurisdictions.

U.S. Electricity Lines and Population Density

Source: https://www.eia.gov/state/maps.php

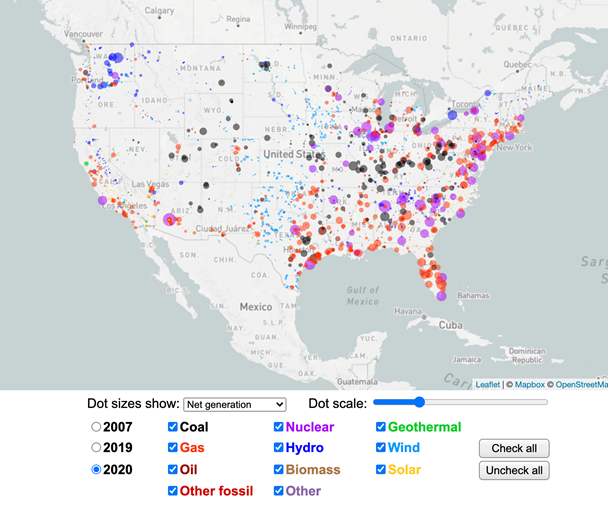

Furthermore, local and regional considerations affect power generation and transmission in each area. Aside from the varied age of electricity infrastructure across the U.S., different regions depend on different energy sources. The Midwest, for instance, has developed its wind generation capacity, while the Pacific Northwest depends significantly on hydropower for its electricity generation. No two markets are alike and approaching each electricity market in the U.S. requires a totally different set of data inputs, and as a result, a totally different strategy. Electricity may be fungible, but different electricity markets in the U.S. can share very little in common, as demonstrated by the map below from Weber State University.

Power plants by type

https://physics.weber.edu/schroeder/energy/PowerPlantsMap.html

Energy trading comes with a host of negative connotations due largely to Enron, which pioneered modern energy trading. Anderson notes, “Enron gave the industry a bad reputation because they were illegally turning power plants on and off to game the system, New rules and regulations make that nearly impossible. Overall, I strongly believe power trading is a benefit to all parties if done fairly and equally. Competition drives down price.”

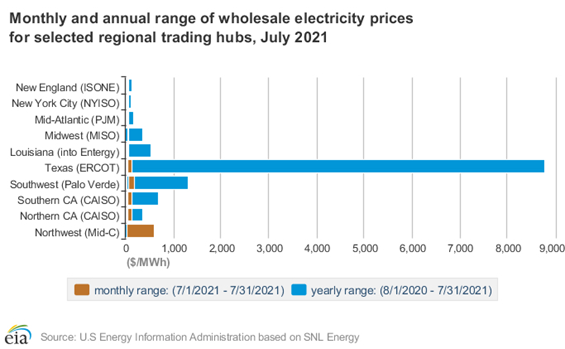

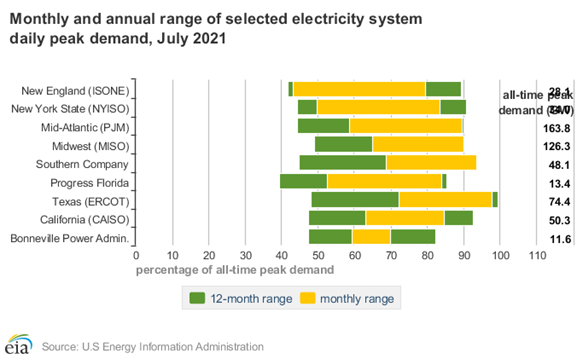

As Hurricane Ida just recently demonstrated, external risks like unpredictable major storms, heatwaves, or cold snaps can exert a massive influence on the electric grid. Furthermore, this is the sort of market where there is the potential for massively different performance – both positive and negative – based on any number of factors, some of which are far outside of a trader’s ability to control, or even know. A few charts below demonstrate the volatile nature of wholesale electricity prices and underscore both the risks and rewards associated with electricity as a commodity.

Like most types of investing, success when it comes to energy trading is about the methodical and yes at times boring work of understanding what is really going on in the market. For each regional market, it involves building a model portfolio, comparing performance at annual and monthly levels, maintaining situational awareness over anything that could possibly create a bottleneck for prices or a sudden surge in demand (as well as a range of technical indicators) and daily vigilance over day-ahead and real-time markets. The learning curve when it comes to electricity is steeper than with most markets, but that is because electricity is the indispensable bedrock of modern life, always taken for granted until supply is threatened, the ephemeral commodity to whose beat all energy commodity markets eventually march one way or another.