I looked through First Horizon Bank’s (FHN) 10K last week. They were in the news because Toronto Dominion (TD) canceled their merger agreement due to uncertainty about when they might receive regulatory approval. FHN’s stock slumped to below $10. The merger price, agreed in February of last year, was $25.

FHN CEO Bryan Jordan told CNBC that he had never been able to ascertain from TD the precise nature of the regulatory impediment that TD was facing. Nonetheless TD had second thoughts and regarded the $200 million break-up fee as better business than paying $13.45BN for a bank whose market cap is now less than half that.

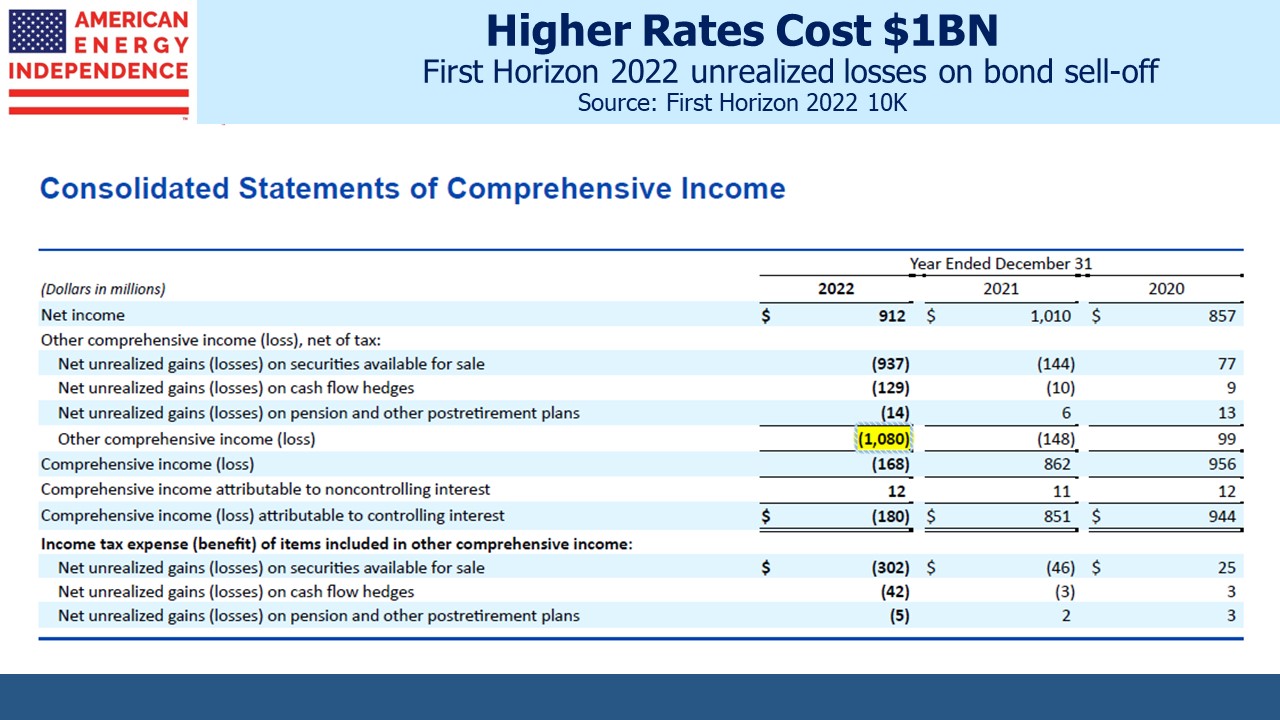

FHN reported $1,159 million in pre-tax income last year, down modestly from 2021’s figure of $1,284 million. This excludes unrealized losses on their securities portfolio and hedges of $1,080 million, reported under Other Comprehensive Income. Including them would have wiped out the whole year’s profit. Perhaps this convinced TD to walk away.

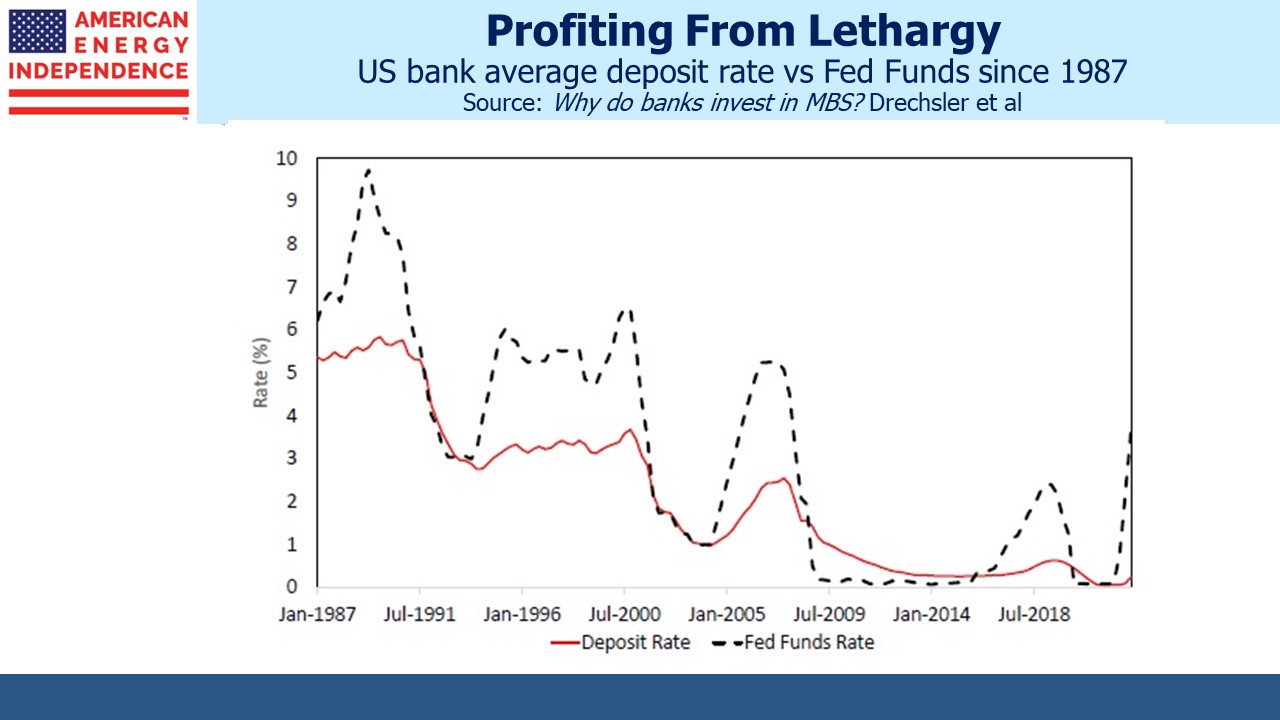

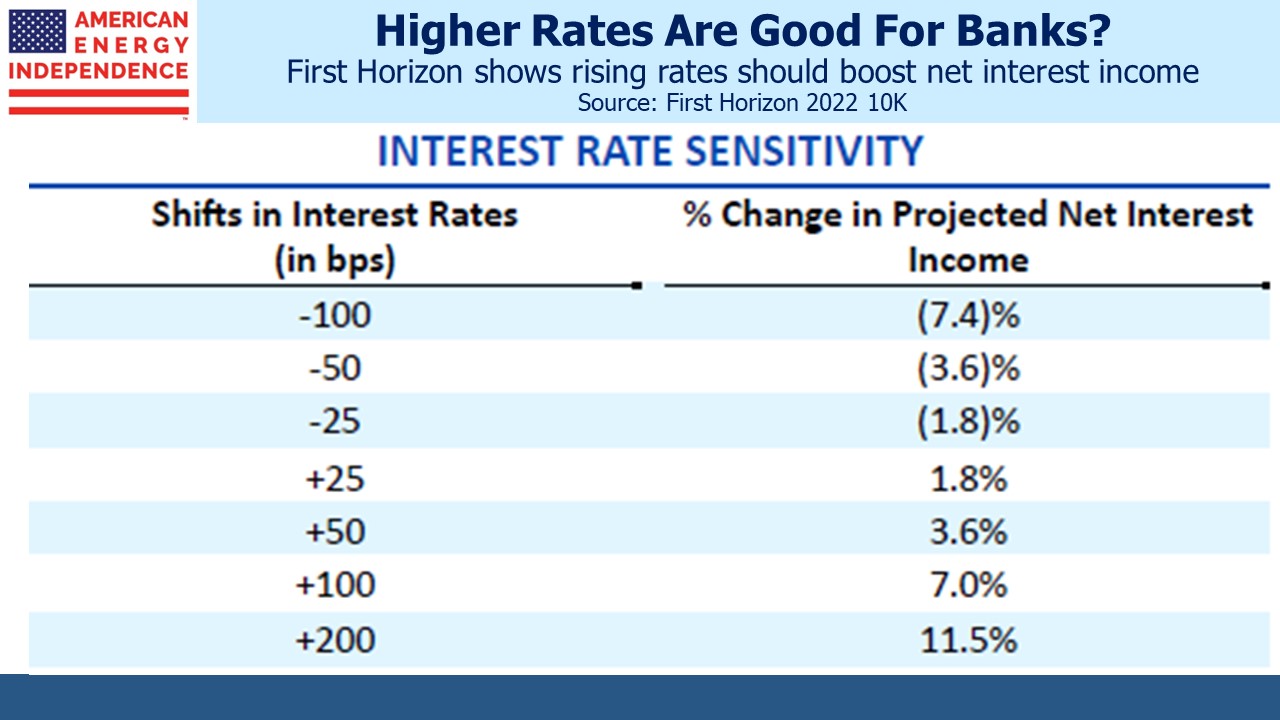

When interest rates depress the value of bonds, banks don’t have to record unrealized losses as long as they have the intention and ability to hold them until maturity. Defenders of this approach argue that higher rates benefit the liability side of a bank’s balance sheet because deposit rates typically rise less than Fed Funds. Revaluing the assets and not the liabilities would present an inaccurate picture. However, it assumes the deposits won’t leave. Banks rely on history to assess the stickiness of their deposit base. Sometimes, as with Silicon Valley and First Republic, they’re wrong.

Deposits are sticky because savers are lazy or unsure how to access better rates using treasury bills. Banks are relying on this historic behavior repeating to fund their underwater bonds with uncompetitive deposit rates.

It costs money to provide banking services, and fees are highly unpopular. So in effect the fees are bundled into the service. Banks don’t pay much interest. That’s the fee.

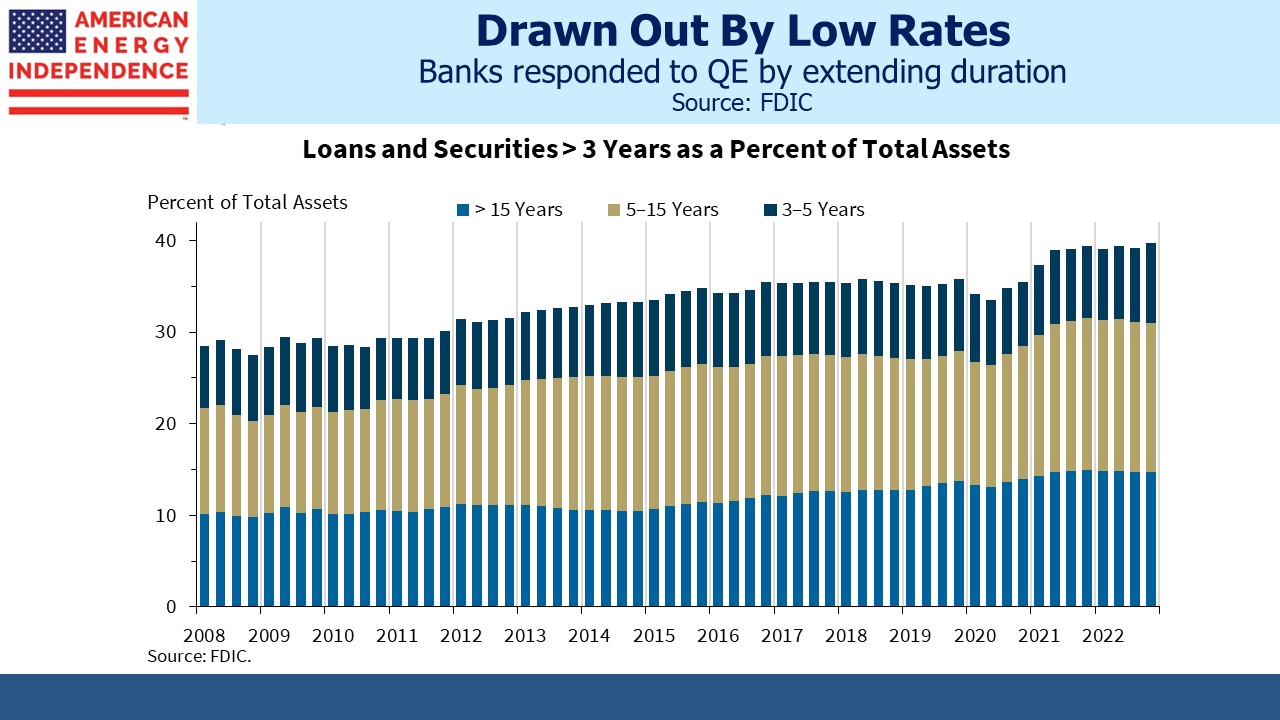

Most of us weren’t watching while banks steadily loaded up on interest rate risk following the 2008 Great Financial Crisis (GFC). Quantitative Easing (QE) was intended to stimulate demand for capital by suppressing rates. But what’s good for borrowers can be bad for lenders. Many banks responded to low rates by increasing fixed rate commercial loans and mortgages. QE was supposed to encourage borrowing, but it also encouraged more long-term lending from banks.

FHN is a portfolio of underwater bonds and loans whose funding relies on uninformed depositors willing to leave money with them at low rates. Banks have always paid uncompetitive rates on savings. It’s part of the business model. It’s why banks traditionally do well when rates go up. FHN’s 10K shows that their Net Interest Margin (NIM) improves with higher rates. In 1Q23 earnings released on Thursday NIM deteriorated in spite of continued Fed tightening. And last year higher rates cost FHN over $1BN.

Like most banks, FHN assumes their deposits are unlikely to leave for higher rates elsewhere. But is that about to change? Silicon Valley caused people to ask two questions: (1) Is my money safe? (2) What interest is it earning?

The Fed has played a significant role in this. Because of QE investors and banks have faced unattractively low rates for years. The Fed was slow to recognize the risk of inflation. As a result, they raised rates faster than many expected. And they didn’t consider the impact on the banking system, which they regulate, of higher rates.

The Fed added to the pressure on regional banks by raising rates last week, further highlighting the uncompetitive rates paid on deposits. An increase in the FDIC cap above $250K would slow the outflow, but what banks really need is lower short term rates. Heavy reliance on large uninsured deposits isn’t every bank’s problem. But holdings of low fixed rate securities and loans are widespread.

America has over 4,000 banks. The figure has been declining for decades. We had twice that number in 1999. This abundance is a uniquely American construct, a legacy of state banking regulations which used to impede expansion. Often the small bank strategy was to be acquired by a bigger one. Today that’s only happening as a distressed sale. We’re learning that there aren’t 4,000 competent chief risk officers employed in the banking system.

Today, why would you deposit cash at First Horizon or indeed any bank beyond the amount you need to keep in a checking account? Fees are disguised as paltry rates on deposits. Banks have insulted our intelligence in this way for years. Rapid Fed tightening is illuminating it.

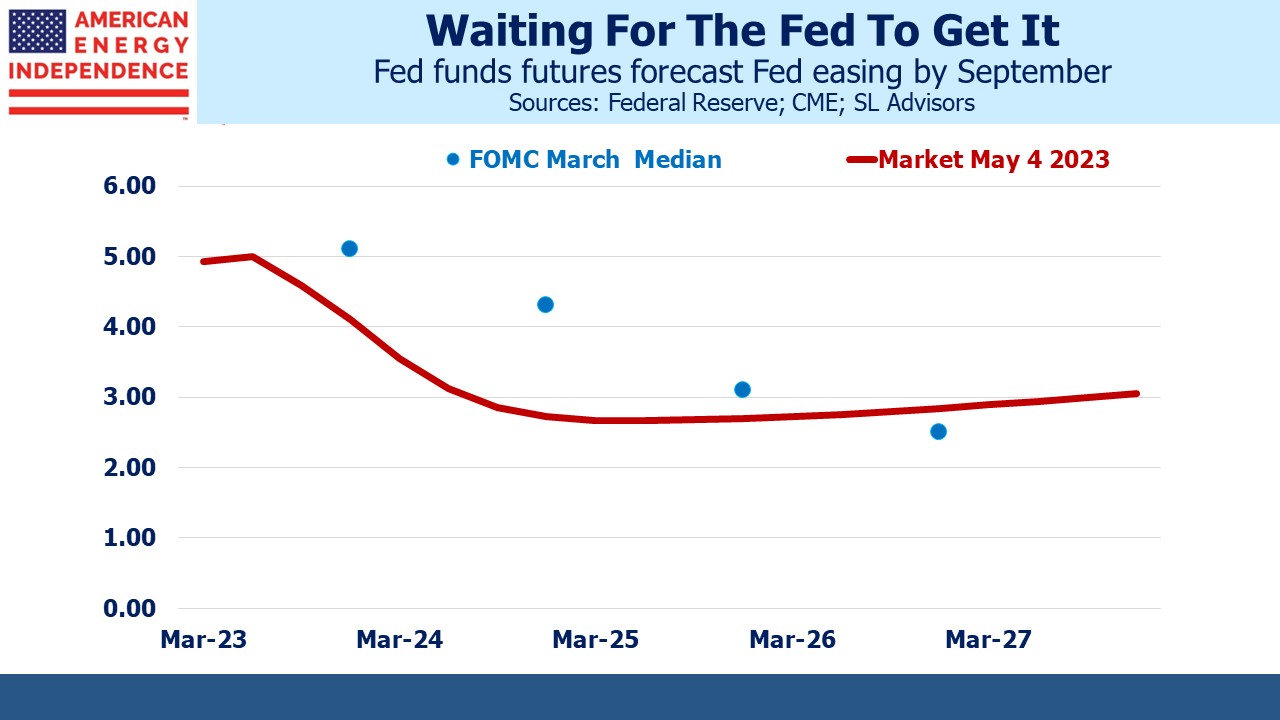

The market is priced for the Fed to provide banking relief in the form of lower rates, this year. The FOMC is in denial – slow as usual to comprehend what’s happening. The regional banking crisis won’t end until the Fed gets it. In the meantime, loan growth at all but the biggest institutions will be constrained by the risk of a rapid loss of deposits and recourse to wholesale funding in the Fed Funds market. Few banks can profitably fund their assets at 5%.

This is why you should bet on 4% inflation instead of 2%. It’s the path of least resistance.

The post Why Keep Money At A Bank? appeared first on SL-Advisors.