Poland has stopped producing fertilizer. Natural gas is a key input into the production of nitrogen-based fertilizers such as urea and Urea Ammonium Nitrate (UAN). The European energy crisis has rendered their manufacture uncommercial because of high natural gas prices, which are likely to persist for at least another year or so. Poland produces 6 million tons annually. Elsewhere in eastern Europe another 3 million tons of capacity is idle. In aggregate, 20% of Europe’s fertilizer production is shut down.

That fertilizer production will still be needed. Last year Russia was the world’s biggest exporter of fertilizer, with a 15% market share. That should presumably drop with sanctions, although countries like India (#3 importer) will probably value feeding their population more highly. The US was #5 exporter with a 5% market share.

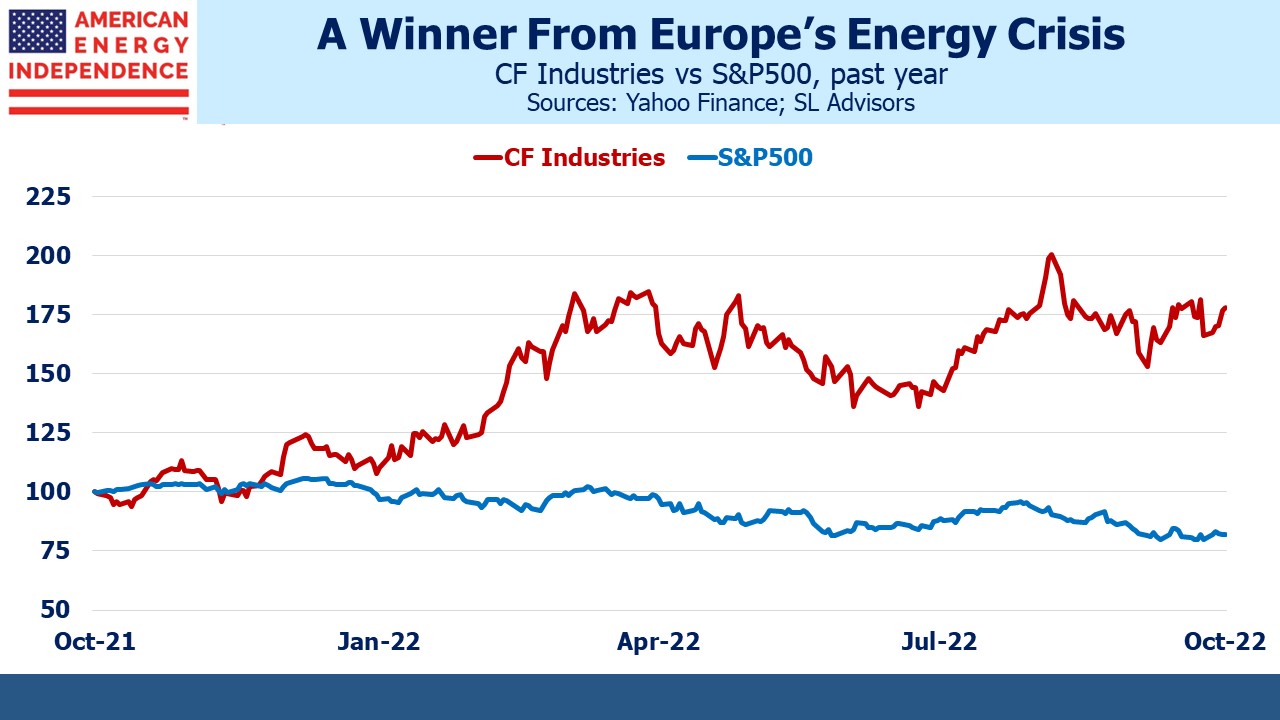

CF Industries has been a beneficiary of America’s comparative advantage in energy availability.

Zinc production throughout the EU has ben curtailed or stopped completely. Dutch company Nyrstar, the world’s biggest producer of zinc, has stopped output. 50% of primary aluminum production has ceased. Goldman Sachs estimates that 40% of Europe’s industry, “is at risk of permanent rationalization.”

Arcelor Mittal, Europe’s largest steelmaker, is idling blast furnaces in Germany. Alocoa has cut a third of its aluminum production in Norway. Hakle, a German makes of toilet rolls, is insolvent.

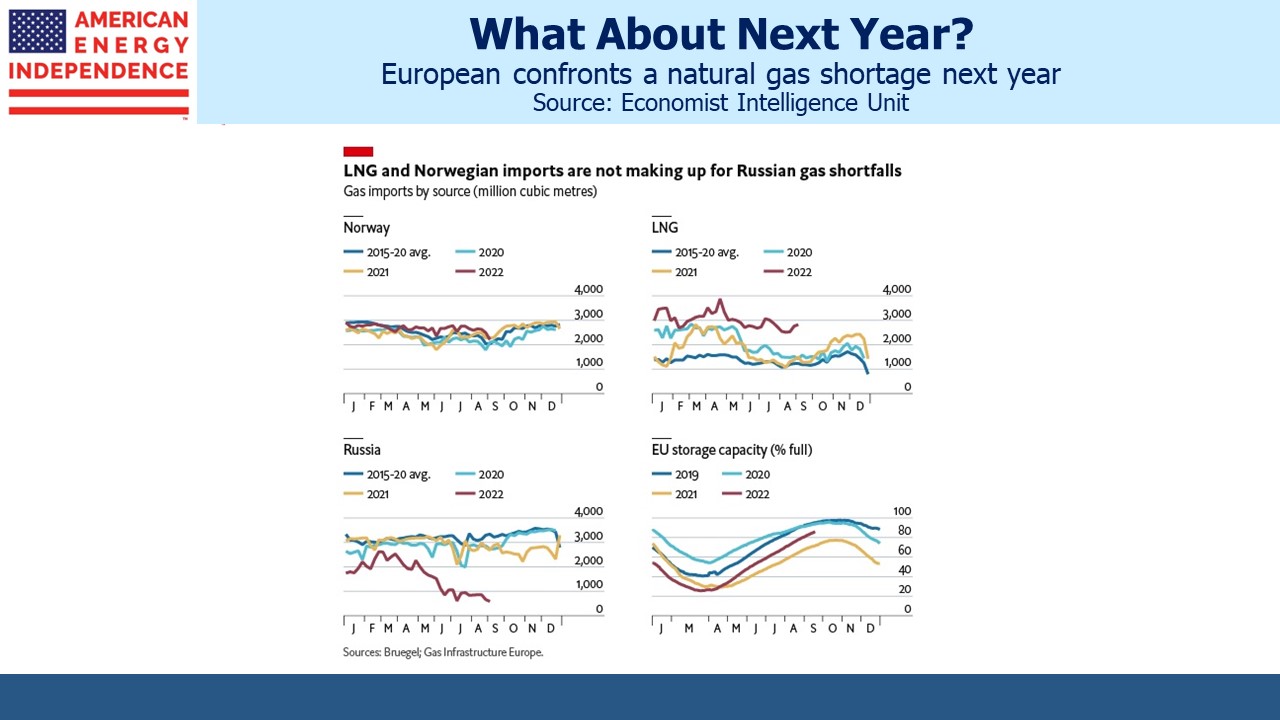

European winter storage levels of natural gas are on pace to be normal, thanks to conservation and increased shipments of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). But analysts warn that replenishing stocks next year will require 20% more natural gas than usual. This will present a potentially bigger challenge, since the partial supplies received from Russia in 2022 won’t be repeated in 2023.

This is why the EU is scrambling to add LNG import capacity. Germany has leased its fifth Floating Storage and Regassification Unit (FSRU). These vessels convert LNG from the chilled form in which it’s transported back into a usable state. They can be deployed relatively quickly, but have less capacity than a land-based, permanent LNG import facility. These can take three years or more to build. Italy hopes to build one by next year, with the government bypassing the normal permitting process, provoking fierce opposition from the local community.

The approach of EU policymakers to the energy crisis continues to regard it as a brief diversion on the way to a 55% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (versus 1990). As a result, they have been reluctant to sign the 20-year LNG supply agreements that are common in the industry. Asian buyers have not hesitated, spurred on by the recognition that they face a new competitor.

Morgan Stanley calculates that agreements totaling over 60 Million Metric Tonnes per annum (MTpa) have been signed since Russia’s invasion in February. European buyers represent just 11 MTpa of this. The Dutch gasfield in Groningen is still scheduled to close by 2024, even though analysts believe it could provide up to half the gas Russia used to supply.

European manufacturers will respond to the energy crisis by overhauling their operations to use less energy. The region’s shift to renewables will receive a further boost from improved relative pricing. But manufacturing will also leave for other parts of the world where energy is cheaper and policies more supportive.

Svein Tore Holsether, chief executive of Norwegian fertilizer giant Yara International ASA, likes the “lower energy prices or green incentives currently offered in the U.S.”

Dutch chemicals firm OCI recently announced plans to expand its ammonia plant in Texas. They plan to use “blue” hydrogen, which is derived from natural gas. They further intend to capture the CO2 emitted in the process, claiming tax credits in the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

No Republican voted for the IRA in either the House or Senate, where VP Kamala Harris had to vote to ensure its passage. It’s ironic that many corporations believe the 45Q tax credits for carbon capture and sequestration are enough to pursue new business initiatives. This includes several midstream companies, generally a group that votes Republican (see Earnings and Pending Legislation Good For Pipelines).

The US stands to benefit from Europe’s energy crisis. It’s likely that manufacturing will receive a boost in parts of the country that offer easy access to energy and a pro-business climate. New England, whose energy policies look decidedly European, is unlikely to be a sought-after destination. Opposition to natural gas pipelines means they regularly import LNG at global rates, now enduring further competition from new European buyers (see Incoherent Energy Policies).

But many other parts of the US including southern states are set to benefit. This should add to demand for domestic natural gas. It shows that energy policy can make a difference.

The post Energy Policies Will Drive Business From Europe appeared first on SL-Advisors.