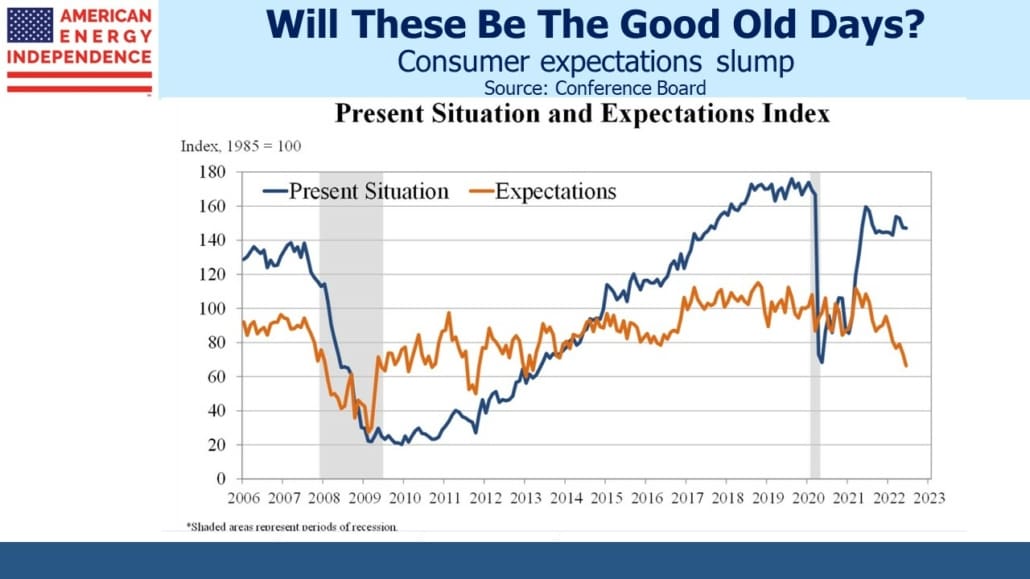

It’s an odd recession when the economy adds 372K jobs and the unemployment rate stays at 3.6%. We seem to be talking ourselves into one. Consumer expectations are the lowest in almost a decade. High prices for energy and food are the culprit. Few are seeing their incomes keep pace with 8% inflation, so real incomes have taken a significant hit this year.

So it’s curious that the measure of how households report their present situation is well above the average since 2006. The gap between today and how people feel about the future is historically wide. A sense of foreboding is creating the type of negative outlook only seen in recessions. Collectively, we saw a brighter future at all times during the pandemic than we do today. Maybe that reflected a recognition that something so bad had to end.

A few weeks ago on Josh Brown’s show The Compound and Friends I drew skepticism when I suggested that we might look back on today as the good old days. Inflation is a problem, but jobs are plentiful. The Conference Board survey data suggests that many respondents feel the same way.

Wall Street is warning that recession odds are increasing. Citigroup puts the odds at 30% within 18 months. Former NY Fed president Bill Dudley thinks the Fed will inevitably cause one in their inflation crusade. He’s betting they’ll follow up one mistake with another. Fed chair Jay Powell says avoiding a downturn largely depends on factors outside the Fed’s control, which is a way of preparing for that second mistake.

With stocks down 20% and bonds down 10%, the classic 60/40 portfolio is down 16% YTD. Regular readers know we have shunned bonds for the entire existence of SL Advisors (see my 2013 book Bonds Are Not Forever; The Crisis Facing Fixed Income Investors). Shoddy thinking is the only explanation for why return-seeking investors still own any bonds. We have often illustrated that a barbell of stocks and cash offers a better risk/return across most scenarios (see The Continued Sorry Math Of Bonds).

The pervasive negativity among consumers, reflected in the weak stock market, is a resounding lack of confidence that the Fed will operate with a deft hand. From this blogger’s perspective over 40+ years, today’s FOMC moves as a group without strong leadership. Powell strikes me as a chair who identifies the consensus rather than creating it the way Greenspan or Volcker did. This means they’ll be slow to shift views, because the group will need to get there together. We saw this with the FOMC’s belated recognition of surging inflation. It’s certainly premature to expect an ease of the tightening cycle, but widespread pessimism reflects a concern that a slothful FOMC shift in consensus will lead to an excessive rate cycle peak.

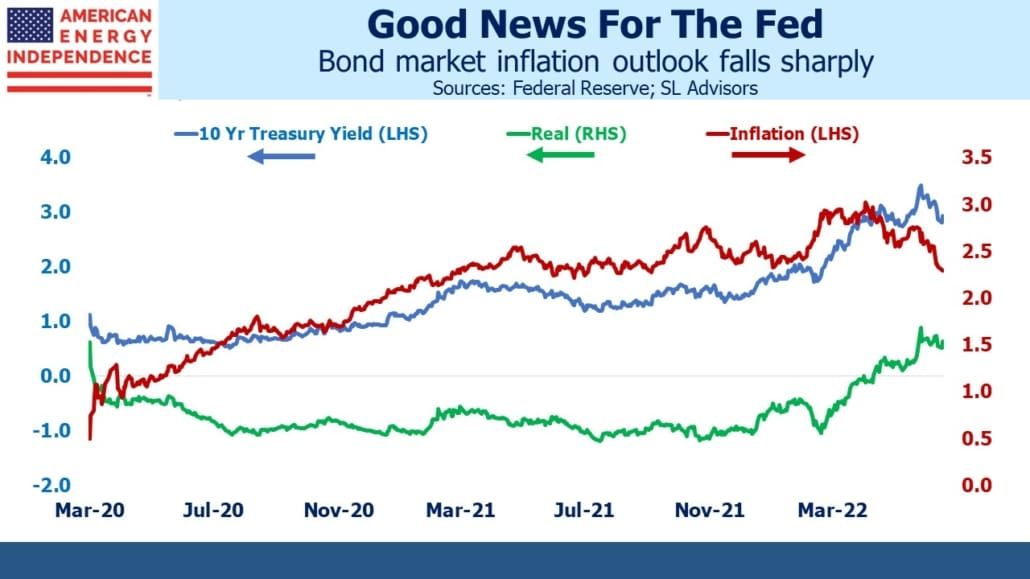

Inflation expectations as measured by the treasury market have fallen sharply in recent weeks. Ten year CPI inflation is priced at 2.3%. Since it’ll be well above that level for at least the next year, the market is priced for the remaining nine years to average at a level very comfortable for the FOMC.

It’s true government bond yields have been distorted for years by non-economic buying by central banks and others with inflexible mandates such as pension funds. This has kept yields lower than they would be otherwise, but presumably such buying pressure works on TIPs as well. If anything, Quantitative Easing had a bigger impact on TIPs than nominal treasuries which, by further depressing real yields would cause implied inflation to be higher. That the Fed is still tightening is a rejection of market-based measures of future inflation. Perhaps they’ve concluded that their activity and that of others have rendered the bond market an ineffective measure of investor expectations.

In recent weeks the market has recalibrated the expected path of monetary policy higher. Meanwhile, signs of a slowing economy are increasing. Most dramatically, crude oil has slumped with December Brent futures falling $20 from their level in early June. GDP projections are being revised down. Bottom-up Factset earnings forecasts are being trimmed, for this year and next.

Goldman Sachs believes the oil market has overshot, with the price drop implying a 1.1% drop in global GDP 2H22-2023. They point out that the current oil deficit remains unresolved. Energy markets have dropped on expectations of lower future demand while current demand is unchanged. Aviation demand continues to recover strongly, spurred by a rebound in international travel. They estimate June demand for crude oil was up 2% year-on-year excluding Asia.

For now it seems investors are more afraid of the future than would seem justified by the present.

Please see important Legal Disclosures.

The post These Are The Good Old Days appeared first on SL-Advisors.