Since we launched our commodities multiverse series back in July (click here if you are new to TSF and want to start at the beginning), we have largely focused on discrete commodities. For example, how the geopolitics of nickel supply will be critical to the future of clean-energy technologies and lithium-ion batteries, or the underlying reasons behind the recent price spike in natural gas prices (and what that says about the future of hydrocarbons as an investment class in the future). This week, however, we will take a step back and tackle a much larger topic, one about which much digital ink has been spilled: data.

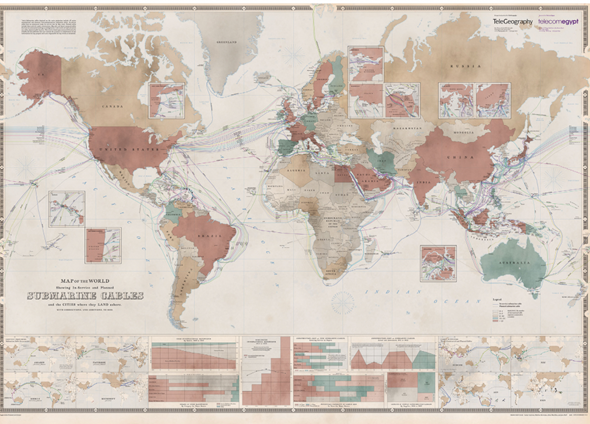

We aren’t the first to herald the importance of data, of course. Such stalwarts as The Economist declared as far back as 2017 that “the world’s most valuable resource is no longer oil, but data.” That’s a pithy headline, to be sure, and there is some truth to it, but the macro-reality, as always, is more complicated than a headline – it’s even more complicated than 1,000 words can hope to sum up here. To understand the importance of data, and how to express that importance in terms of investments, let’s start with something that is simultaneously simpler and more complex: A map. This is just not any old map, however. The image below shows the plumbing of the modern economy – the underseas cables that create the digital environment that allow you, dear reader, to consume this content wherever in the world you are sitting.

TeleGeography 2020 Submarine Cable Map

Source: Jayne Miller, “The 2020 Cable Map Has Landed,” TeleGeography Blog, June 16, 2020, https://blog.telegeography.com/2020-submarine-cable-map.

Life as we know it would not have been possible without three Industrial Revolutions. These revolutions, which should be thought of as ongoing processes rather than discrete and mutually distinct eras, occurred at varying times over the last three centuries (and continue to evolve today). Each transformed the way humans live and think and work. The First Industrial Revolution, which occurred from roughly 1760-1840, owed largely to the advent of steam power, and the accompanying increases in the capacity and productivity of mechanical production. The Second Industrial Revolution, which occurred from roughly 1870-1914, was powered by electricity and the internal combustion engine, allowing the production of economies of scale and a range of new technological innovations. The Third Industrial Revolution, often referred to as the Digital Revolution, began in earnest in the 1960s, enabled by the invention of semiconductors, ushering in a new age of connectivity.

Note that “data” was a part of all these revolutions. Data, after all, is just a fancy word for information. A British textile manufacturer in 1780 was producing “data” when he or she recorded in a logbook by hand how much cotton was being imported and how much clothing was, in turn, being produced from that cotton. Indeed, each successive Industrial Revolution was driven by the ability for manufacturers, corporations, and states to gather still more data, and to use that information to make economic life more efficient. As supply chains globalized, and goods and services began traversing multiple borders, copious amounts of information were generated, logged and monitored by increasingly powerful computers and mobile devices. In each of these revolutions, however, more data was a byproduct of other advances. Data itself was not primarily revolutionary in its own right; rather, the expansion of data was a symptom of other fundamental changes within the global economy.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution is upon us. It has been since 2011, when the phrase “Industry 4.0” was coined at the Hannover Messe trade fair in Germany. (If you haven’t read

The Fourth Industrial Revolution published by Klaus Schwab in 2017, now would be a good time to familiarize yourself before the world passes you by.) The Fourth Industrial Revolution is going to be a revolution powered by data. That is where the oil metaphor is accurate – in the same way that hydrocarbons, often pumped to different locations via pipeline, helped power everything from tanks to cars to electric grids in the 20th century – data is going to power many aspects of the 21st century economy, pumped to different locations via subsea cables (and perhaps via satellite, though that is still in its infancy – satellites carry less than 5 percent of voice and data traffic globally).

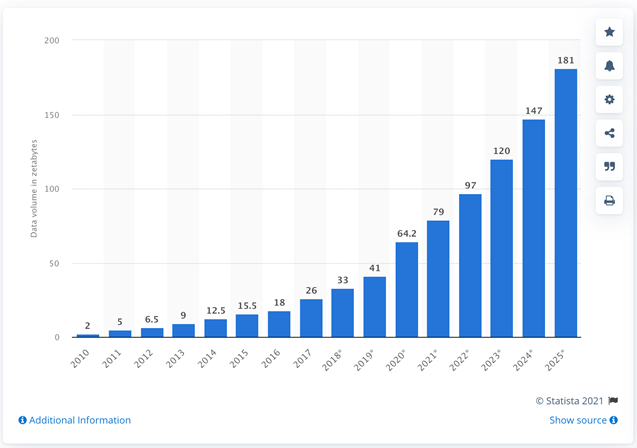

Volume of data/information created, captured, copied, and consumed worldwide from 2010 to 2025(in zettabytes)

Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/871513/worldwide-data-created/

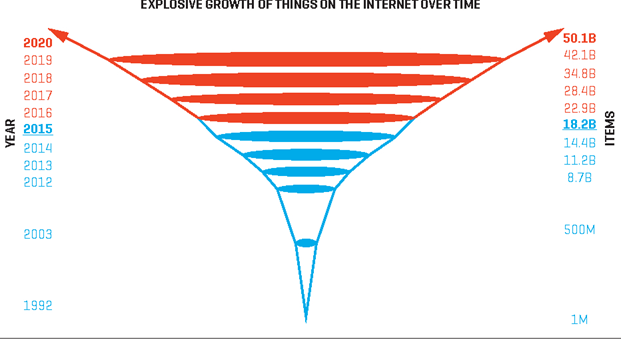

Just look at the chart above. Humans are creating exponentially more data with each successive year. The chart above is measured in zettabytes, which is equivalent to the 1021 bytes. Gone are the days when downloading a few songs or videos, with file sizes in the tens of megabytes, off the internet might exhaust your computer’s memory. Indeed, according to the International Data Corporation, “The amount of data created over the next three years will be more than the data created over the past 30 years, and the world will create more than three times the data over the next five years than it did in the previous five.” Furthermore, the consumer share of this global “datasphere” will hover around 50 percent over the next five years, at which point it will slowly begin to cede share to the enterprise datasphere. Crucially, this is being driven by the “Internet of Things” (IoT), an unnecessarily intimidating term that just means as more devices get connected to global networks, infinitely more data will be produced. From the ap on your phone that lets you change the air conditioning temperature while you are away from home, to self-driving cars, to factories where each piece of equipment is connected to a network and tracked closely (still more data), data is going to increase. Not only that, but the data itself will be driving the economy. Self-driving cars, for instance, will produce data in real time, and will need to be connected to networks with low latency (i.e. without delay) and that are constantly available.

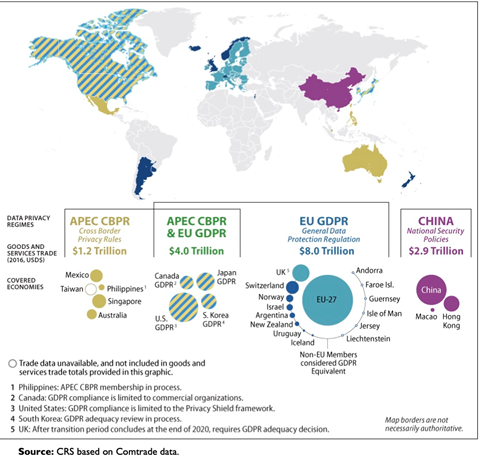

The promise of the internet and the heady, idealistic day of the 1990s imagined a world that would be connected via a single network (the internet). In practice, however, even in the 1990s, some countries had different ideas. China’s so-called “Great Firewall” was for many decades just an inconvenience, one you could get around with a good virtual private network (VPN). Now, however, as governments wake up to the fact that data isn’t just being generated by the economy but is becoming the economy, they are engaging in digital protectionism. This ranges from building their own internets (like Russia and China), to protocols designed to protect the sovereignty of their citizens’ data, to investing in/commandeering the submarine cables that connect everything. As far back as 2012, a U.S. Army War College report warned that “destruction of submarine cables can cripple the world economy including the global financial market and/or Department of Defense.” That vulnerability has only been heightened in recent year as data has proliferated at exponential rates.

Goods and Services Trade under Differing Data Privacy Regimes

Source: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45584

Let’s stop for a deep breath. It is hard enough to wrap one’s mind around the pace of change that is happening around us. It can feel intimidating – like you might need an advanced degree in computer science to under things like zettabytes, the “Metaverse,” and the underlying plumbing behind everything from the internet to 5G. It may feel even more daunting to begin to figure out from an investment perspective how to understand, react, and prepare for these revolutionary (the word is not an exaggeration) changes occurring within the global economy. The macro-approach, however, is not daunted by the scope of the change occurring. Like any phenomenon, once you can break the event down into its fundamental parts, you can begin to understand how different key sectors stand to either profit or suffer from change. In the case of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, we’d start a mental map with three key fundamental parts: semiconductors, cloud servers, and undersea cables.

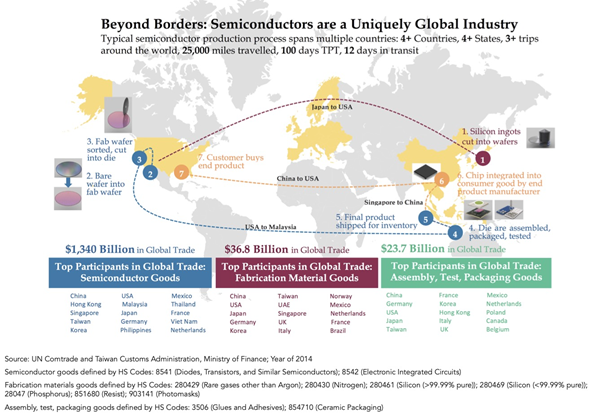

Source: https://www.semiconductors.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/SIA-Beyond-Borders-Report-FINAL-June-7.pdf

Perhaps no industry benefited more from globalization than semiconductors. Today’s most advanced computer chips are a product of a global and complex supply chain, each node optimized for maximum efficiency and productivity of a small subset of the overall manufacturing process. The map below illustrates this well. The semiconductor industry is now in a state of flux, as different nations desire independence within the supply chain. Taiwan, which is by far the global leader in the global semiconductor foundry market at 53 percent of the total, also happens to be one of the most geopolitically contentious areas in the world. The U.S., Japan, the EU, and China are all scrambling to rebuild their semiconductor supply chains, as smaller and more advanced chips are crucial to the data economy, which is always looking to go faster, smaller, and more efficient.

Cables’ Public-Private Ownership Breakdown (December 2020 Snapshot)

Source: Data from TeleGeography’s Submarine cable Map, visualized by Justin Sherman at The Atlantic Council https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/cyber-defense-across-the-ocean-floor-the-geopolitics-of-submarine-cable-security/

We began this post with a map of undersea cables – the “pipelines” of the data economy, if you’ll forgive the crude metaphor. (Pun intended.) The thing to note here is that there is a global scramble to secure access to these cables. States are increasing their ownership over cables so that they do not have to reply on private companies. Currently, the global market for submarine optical fiber cables is estimated at US$13.3 Billion and “is projected to reach a revised size of US$30.8 Billion by 2026, growing at a CAGR of 14.3%.” Countries like China are rushing to build or acquire their own submarine cables, while major U.S. tech companies are preparing for a more competitive world by investing in this strategic infrastructure, without which they cannot provider their cloud-based services.

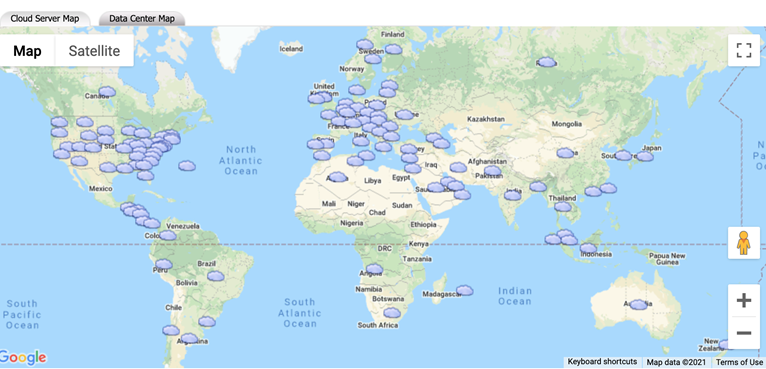

Source: https://www.datacentermap.com/cloud.html

Which of course leads us to cloud centers and data centers themselves (the map above is restricted to just the former). Even the cloud is dependent on physical infrastructure, in the form of data centers and critical infrastructure (like maritime cables), often transmitting massive amounts of data based on operations in multiple countries. This is an entire sector in and of itself and includes everything from security (both physical and digital) to all the subcomponents that are involved in building data and cloud centers at scale. As data flows grow, the need for more bandwidth and for more storage capacity will increase along with it. U.S. companies like Google, Amazon, and Microsoft dominate this space, but as with semiconductors, other countries (especially China but also the EU) are looking at ways to support their own cloud champions so they are not dependent on the whims of U.S. politics.

This is hardly an exhaustive take, nor is meant to be. It is simply a way of shaking out the cobwebs. Arguably, the last few centuries of technological development have been unmatched in human history. The revolutionary industrial and technological processes that have led to the incredible changes in how we think, work, eat, and live are not static, nor have they run out of steam. Hard as it may be to believe, the last few decades have been the latter stages of the Digital Revolution – a honing of and perfection of revolutionary technologies. Now a new revolution is beginning, and while its impact will be felt across almost every market conceivable, there are two things to keep in mind: 1) This is the dawn of the data revolution, and 2) Semiconductors, underseas cables, and cloud/data centers are at the heart of these changes. In that sense, data is not just a commodity – it is fast becoming the circulatory system of the entire economy, and a range of new industrial commodities will be crucial to its circulation. Investors should take note and make sure they are positioned to harness this deep and rich investment universe. Leaps in innovation that reached across key global industries has persistently created the most wealth.