Inflation is probably the biggest known risk facing equity markets today. Last week’s CPI report was expected to be high and still exceeded expectations. The 4.2% year-on-year increase in the All Urban Consumers index (CPI-U) was boosted by comparisons with a year ago. The Fed, and many economists, have warned of the transitory base effects as weak readings from the start of lockdowns drop out. The CPI-U less food and energy is running at 3% p.a., although as is often pointed out eating and driving are not optional even if their costs are volatile. Most striking was the 0.9% monthly jump in CPI-U ex food and energy. Used cars and trucks were up 10% and contributed a third.

The Fed expects inflation to temporarily increase before supply constraints ease, moderating price hikes. Investors aren’t so sure, given the Fed’s stated willingness to tolerate higher inflation until they’re sure we’ve reached full employment. Under such circumstances, the term structure of interest rates should reflect a premium above the Fed’s guidance. The FOMC projects an unchanged policy rate through at least 2023, whereas eurodollar futures are priced for tightening at the start of 2023 and 0.75% by year’s end.

We’ve noted before the FOMC’s poor forecasting record, even of their own policy rate (see Bond Market Looks Past Fed). Markets are skeptical about the Fed’s resolve to maintain expansionary policies in the face of rising inflation. It’s analogous to when a central bank defends a currency peg. Credibility counts for much, and the 0.75% gap between market rates and FOMC projections measures the degree of investors’ disbelief.

Price hikes are visible everywhere. Many corporations report price pressures. Warren Buffett noted that suppliers were increasing costs to them which were being passed on and accepted by customers of Berkshire’s many operating businesses. Hiring is hard. The non-farm payroll report fell well short of the one million jobs expected, but rising hourly earnings suggest more labor tightness than the 6.1% unemployment rate implies. There’s reason to suspect that job growth was constrained by insufficient availability of qualified people.

Criticizing the Fed is a time-honored self-indulgence but not very profitable. More useful is to figure out how to act on it. Partial debt monetization synchronized with excessive fiscal stimulus is so obviously designed to cause inflation that investors should align themselves with the government’s actions, not their benign inflation forecast.

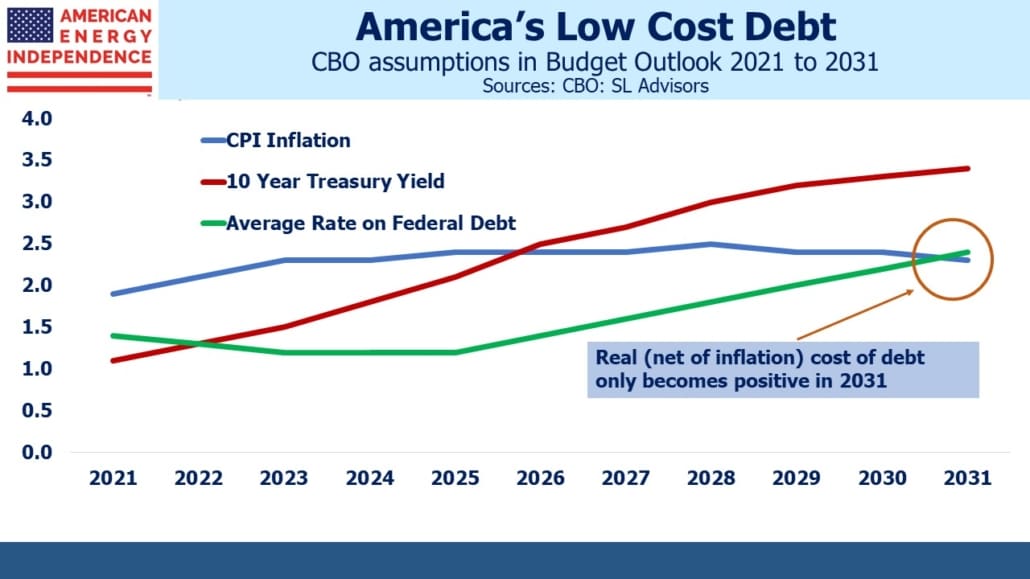

Total Federal debt is $28TN. Its cost of financing will increasingly drive America’s fiscal outlook. Many will be surprised to learn that the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) expects net interest expense as a % of GDP to fall over the next few years – a consequence of higher yielding securities maturing and being replaced. The average rate on government debt will fall from 2.1% last year to 1.2% in 2023 before climbing back up to 2.2% by 2030.

Fiscal conservatives will identify much of concern in this. Ten-year market-based inflation expectations are above 2.5%, a level the CBO doesn’t expect even in a single year. In March the CBO forecast the ten-year treasury will average 1.1% this year, whereas it’s already averaged 1.4% over the first four months or so.

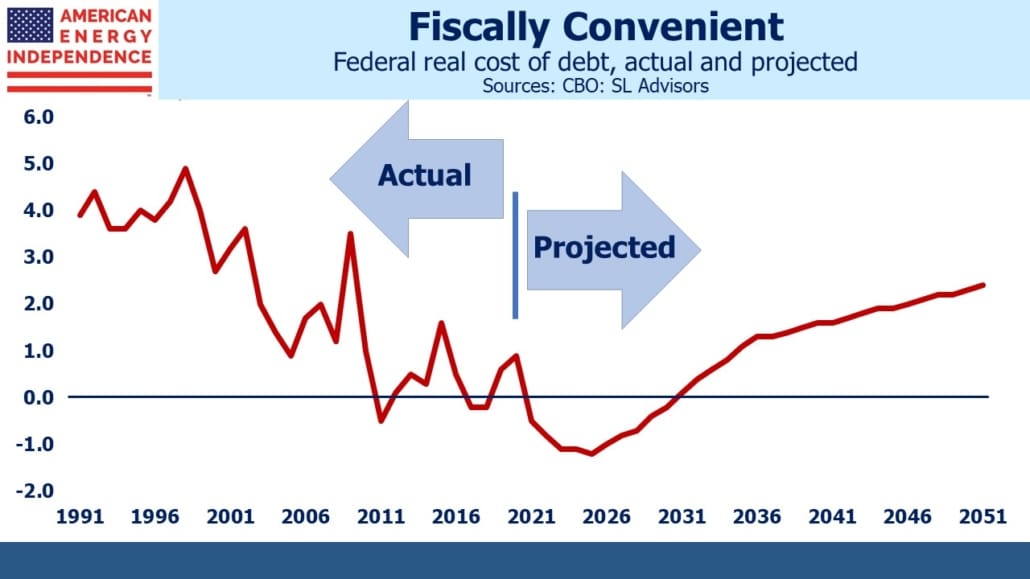

Moreover, the CBO forecasts that the Federal government’s real cost of debt, defined here as the average rate less CPI-U inflation, is about to go negative and remain there for the next decade. U.S. Debt:GDP is forecast to reach 107% by 2031, the highest in the nation’s history. Is it reasonable to expect that the U.S. will borrow at negative real rates with such a fiscal outlook?

As sobering as these charts are, the MMT crowd (see Modern Monetary Theory Goes Mainstream) will press to exploit the underutilized borrowing capacity negative real rates imply.

This is why the Fed’s continued bond buying is poorly advised. The risks to America’s fiscal outlook are skewed in one direction. It’s likely that the CBO’s projection of negative borrowing costs for the next decade will require continued growth in the Fed’s balance sheet. The Fed may be right that inflation will return to 2% next year, but they face asymmetric risks.

Prudent management should have prompted them to dial back as soon as it became clear that the stimulus checks were being distributed coincident with the vaccine. They should have withdrawn when there was no political pressure to continue. If fiscal profligacy drives rates higher, MMT proponents (i.e. progressive Democrats) in Congress will be quick to pressure the Fed back in.

But the Fed didn’t — and America’s fiscal outlook increasingly relies on negative real rates to fund its debt, which means higher inflation, more debt monetization, or both. As Washington pursues additional spending on infrastructure and welfare, further increases in borrowing are the path of least resistance.

Markets are adjusting to the new normal. Pipelines are cheap and one of the few sectors to offer inflation protection.

We are invested in all the components of the American Energy Independence Index via the ETF that seeks to track its performance.

The post Inflation – Back By Popular Demand appeared first on SL-Advisors.