“Let us set as our national goal, in the spirit of Apollo, with the determination of the Manhattan Project, that by the end of this decade we will have developed the potential to meet our own energy needs without depending on any foreign energy sources.”

Over 47 years ago, President Nixon set out this vision. Securing oil supplies from a region of the world that often seems hostile to the U.S. has driven foreign policy ever since.

Four years later, President Carter warned in a speech to the nation that, “We can’t substantially increase our domestic production, so we would need to import twice as much oil as we do now. Supplies will be uncertain. The cost will keep going up. Six years ago, we paid $3.7 billion for imported oil. Last year we spent $37 billion — nearly ten times as much — and this year we may spend over $45 billion.”

Last week, following Iran’s deliberate miss of U.S. forces in Iraq, President Trump said, “…our economy is stronger than ever before and America has achieved energy independence (emphasis added). These historic accomplishments changed our strategic priorities…We are now the number-one producer of oil and natural gas anywhere in the world. We are independent, and we do not need Middle East oil.”

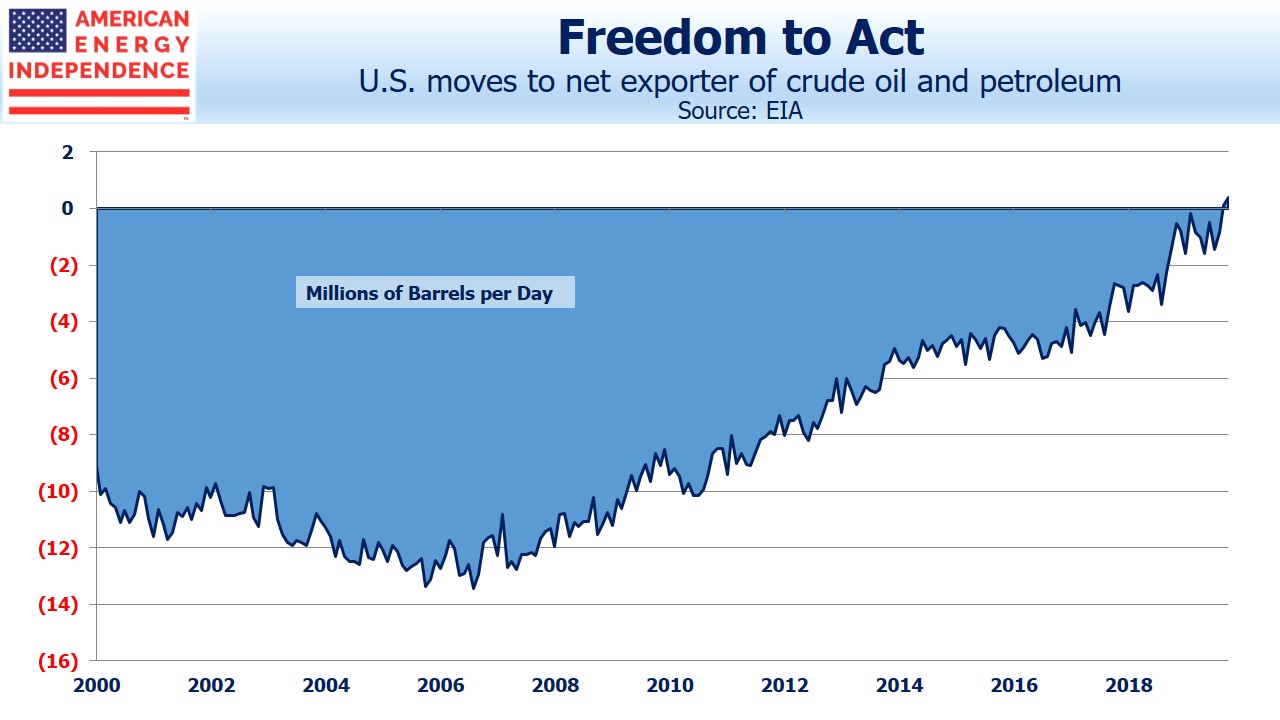

In November, the U.S. was a net exporter of crude oil and petroleum products for the first time in decades, a development made possible by the Shale Revolution. Increased freedom of action is one of the many benefits, as Iran is finding out.

Some have noted that the figures don’t show that the U.S. is a net oil exporter, which is true (see America Is Not Yet A Net Crude Oil Exporter). Domestic production is currently 12.9 Million Barrels per Day (MMB/D), and consumption of refined products is around 20 MMB/D. The difference is made up by 5 MMB/D of Natural Gas Liquids (NGLs), of which 3 MMB/D is consumed domestically, much of it as inputs into the petrochemical industry; 1.0 MMB/D of ethanol; and 1.1 MMB/D of net refinery processing gains. Net imports of crude oil make up the difference.

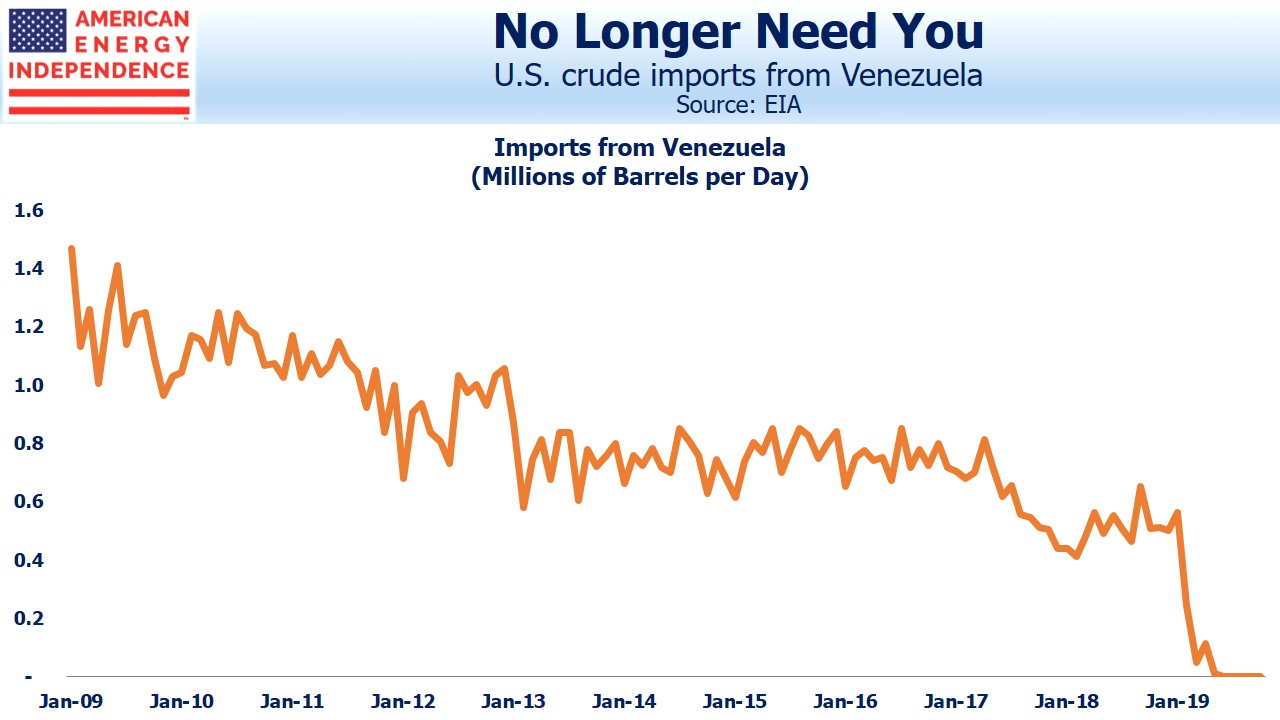

Crude oil comes in hundreds of grades, and it’s often reported that U.S. refineries are better equipped to process the heavy crude that Venezuela and Canada produce, with limited capacity to handle the light crudes that come from the Permian in west Texas. So we trade with other countries to achieve the desired mix of blends.

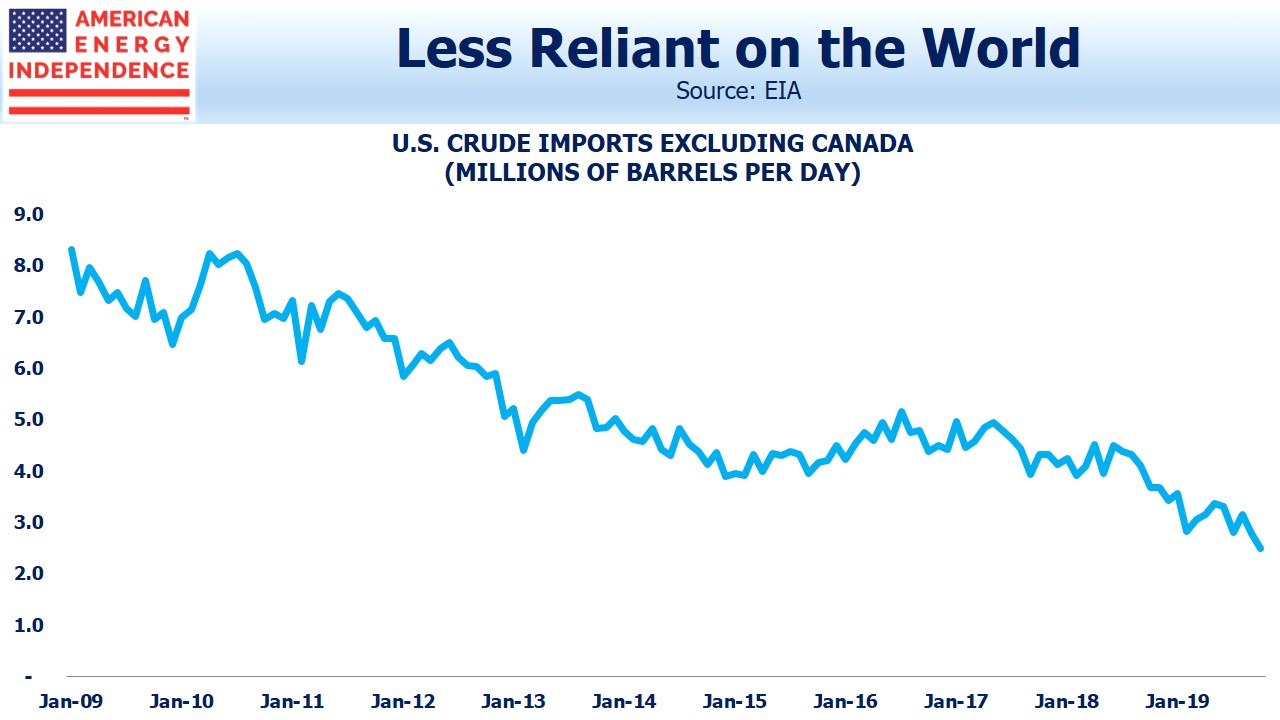

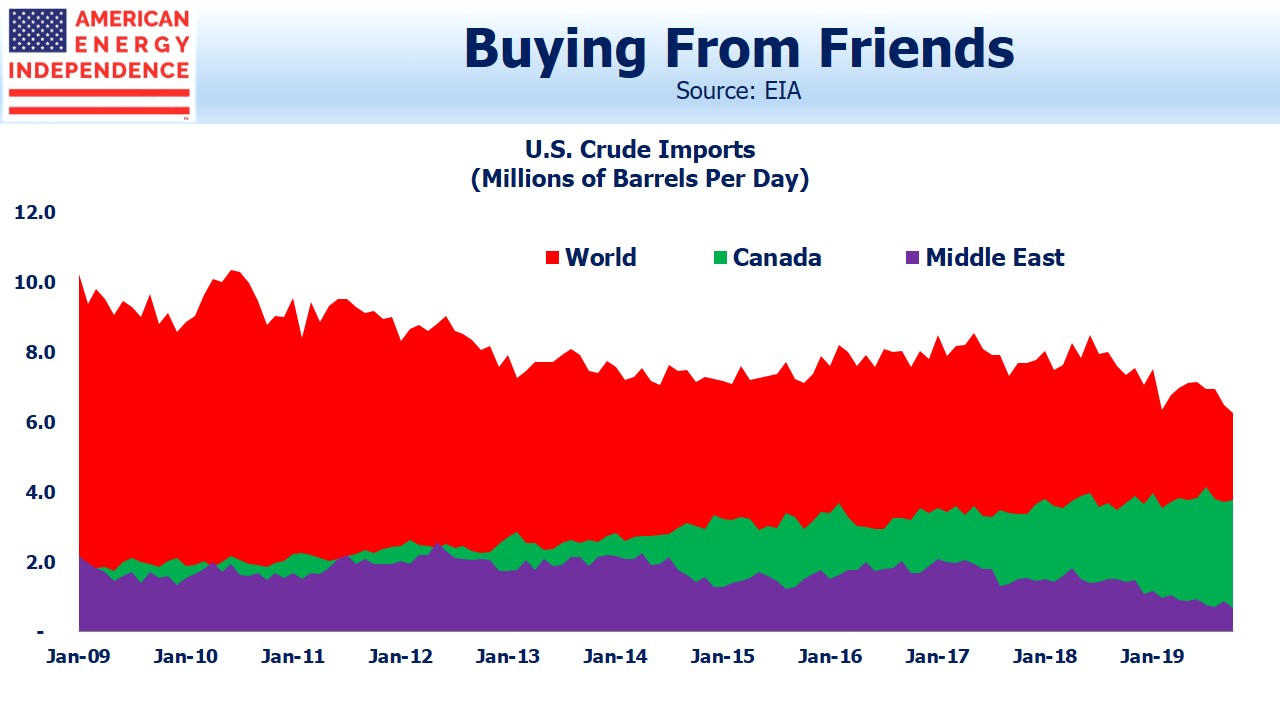

Imports from Venezuela have collapsed to almost zero from 1.2 MMB/D a decade ago. Imports from the Middle East have fallen to 0.7 MMB/D, so it wouldn’t be hard to get by with no Middle East imports at all. Meanwhile, Canada’s continue to grow.

From an energy independence perspective, Canada’s oil imports are hardly at risk. Its oil is produced in Alberta and runs south through pipelines to refineries in the Midwest, and even all the way to the U.S. Gulf coast. Two thirds of Canadian production is the heavy blends suited to U.S. refineries, and we buy 80% of their production. Canada has little choice other than exporting to the U.S. Domestic politics has prevented the construction of additional pipeline capacity from Alberta to Pacific coast ports in British Columbia (see Canada’s Failing Energy Strategy).

So even though there’s two-way trade in crude oil to achieve the blends needed for U.S. refineries, our imports are increasingly coming from friendlier countries.

The net result is that the U.S. is not only net independent in crude based products, but our imports of the blends of crude we prefer are coming from friendly countries. It’s a truly incredible outcome, and midstream energy infrastructure is vital to this success.

For a list of the most important companies in this sector, look at the American Energy Independence Index.

The post Energy Strengthens U.S. Foreign Policy appeared first on SL-Advisors.