One of the major benefits and selling points of a structured annuity is the “definition” it provides. The segment portion of the structured annuity spells out exactly what the purchaser will receive at maturity based on how the underlying security performs. Outcomes in general markets are ambiguous at best creating unease among investors. The ability to have any element of an investment concrete is a tremendous benefit. Knowing that if the S&P 500 drops 20% over the period of your segment and whether your segment contains a 15% buffer which will allow for only a 5% loss is significant. Now the issuers ensure that the world fully understands this benefit. What about the detriments?

There are two major detriments that we will focus on today, both which affect longer dated segments more than their short-dated brethren. The first detriment is the lack of dividend paid out on the segment. A structured annuity does not hold the underlying security but rather creates the exposure to that security using options. Options do not capture the dividend. Therefore, performance in options-based products, such as the structured annuity, is based on “price return” as opposed to “total return.”

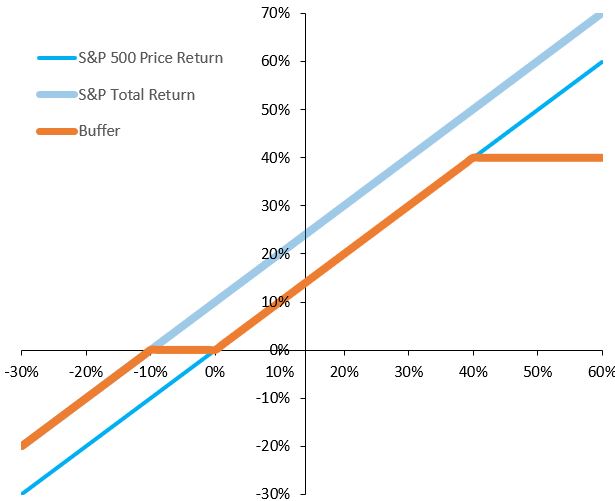

The S&P 500 annual dividend yield is approximately 2%. That means that the total return will outperform the price return by 2%. If one purchases a one year 10% buffer on the S&P 500 they only have 8% protection compared to an investor in SPY (the S&P 500 ETF). Applying that same logic to a five-year 10% buffer on the S&P 500 would result in no better protection then the aforementioned SPY ETF.

A 5 year 10% Buffered Note on the S&P 500 never has an advantage as compared to the total return of the S&P 500

The second major detriment is the limited ability to rebalance and refresh one’s exposure level. For example, let’s say one purchases a one-year 10% buffer with a 12% cap on the S&P 500 on December 31, 2018. If the S&P 500 increases 10% in the first two months of the year, like it did this year, the segment, according to the way most contracts are written, would only gain approximately 1.7%. Yet, odds are now much higher that the S&P 500 will surpass the cap by the end of the term, given only 2% more to go. This makes it exceedingly difficult to readjust one’s buffer and cap without generating significant costs.

Applying this same detriment to a five-year product really exposes the issues at hand. Let’s use a five-year, 10% buffer with a 90% cap on the S&P 500 and assume the S&P 500 is up 20% in year one of the product. Well now, the holder of the structured annuity has 20% of S&P 500 risk prior to the S&P 500 getting to the buffer level. Additionally, the holder does not capture the 20% gain until the five-year mark is complete. The math in the contract generally has minimum of return or cap multiplied by time expired over duration (e.g., 20% * 1/5 in this example which equals 4%).

In summary, the benefits of definition may come with material detriments that are not as clearly illustrated or potentially defined by the issuer. The longer the time frame of the product, the more these detriments affect the overall ability of the investor to appropriately manage their hedges and upside exposure. For example, it is hard to see how a five-year 10% buffered structured annuity on the S&P 500 will ever outperform the SPY.