Since launching our ambitious series on commodities, we have spent a significant amount of time on energy. That’s with good reason: according to the latest reading of the U.S. Consumer Price Index that has markets jittery and the Federal Reserve dreaming of interest rates, energy prices are up 33 percent, compared to 6.8 percent for all goods. But if energy prices have spiked suddenly, hiding in plain sight of the global inflation story are food prices, which have steadily increased since May 2020, when pandemic-related economic shutdowns started impacting agricultural supply chains.

Source: UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Perch Perspectives

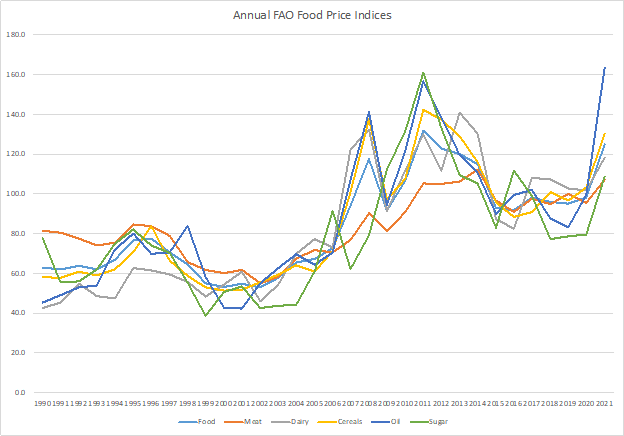

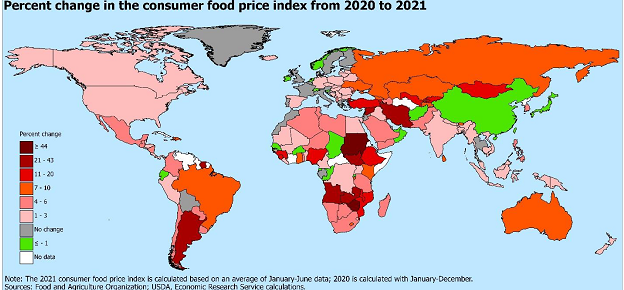

Two things should jump out at you from the chart above. The first is obvious: food prices are extremely elevated across the board. Secondly: The last time food prices were trending this direction was 2008. The sudden spike in global food prices played a significant role in the so-called “Arab Spring,” which began when a Tunisian vegetable salesman self-immolated. The subsequent Egyptian coup, the Syrian Civil War, the rise of the Islamic State, the U.S.-Iran Nuclear Deal – in a certain sense, all these things were caused by the sudden jump in food prices. The chart below is a way of benchmarking where higher food prices could translate (or already is translating) into political instability in the year ahead.

“Food,” of course, is an incredibly broad category, even more so than, say “hydrocarbons.” In the case of the latter, the price movements of crude, natural gas, coal, and other hydrocarbons are related but also highly idiosyncratic based on the commodity in question. The same is true of food. And so rather than attempting to present a grand unified field theory of food prices in 2022 in the limited space we have here, we want to take a deeper dive into a single food commodity, one of the most important and taken for granted in the world: wheat. We’ll address other specific food commodities in future editions.

Global Wheat Prices, USD per Bushel

Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/commodity/wheat

Again, the story here is similar to the UN data on food prices globally. Wheat prices doubled in 2008, and while prices spiked again in 2011 and 2013, the trajectory of global wheat prices was generally downward, so much so that many analysts were predicting “disappointing wheat prices” going into 2020. Instead, global wheat prices have steadily moved upward, and while they are still significantly below their 2008/09 peaks, the question is whether 2022 will see a return to the previous downward trend – or whether the last two years have simply been the overture to a sustained rally in global wheat prices across the globe.

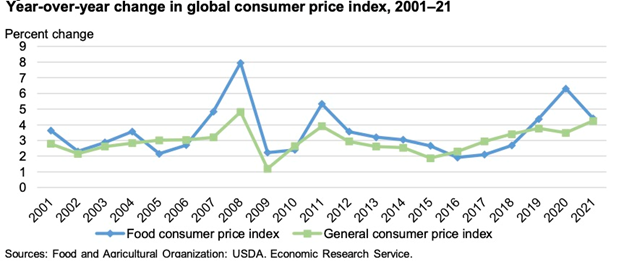

At first blush, there seems to be good news on that score – at least, good news for those of us who eat pizza. Even after reducing its forecast for annual cereal production by 2.1 million tonnes, the FAO still predicts overall production of 2,791 million tonnes – a new world record. Furthermore, though food prices continue to rise, they are rising slower than the general consumer price index in the United States.

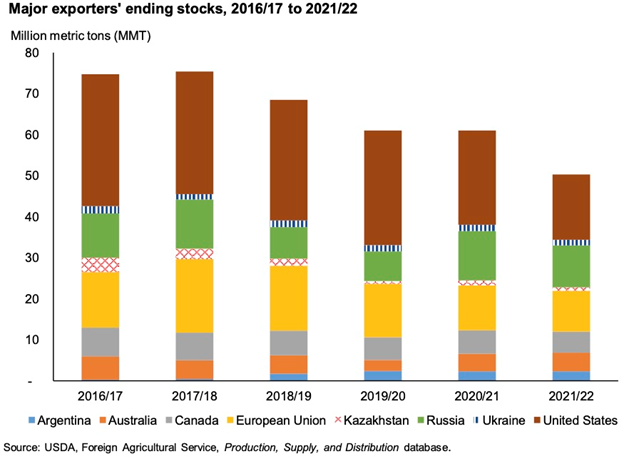

Start to scrutinize the fundamentals of global wheat prices, however, and things start to look a little less sanguine. For one thing, global ending stocks for the major global exporters of wheat are expected to decline considerably compared to 2020/21 – to the lowest ending stocks since 2007/2008. In addition, China – arguably the most importer global consumer of imported grains – has managed to boost its domestic grain production to a record 682.9 million tonnes this year. That’s bad news for global farmers, as it will tame global wheat prices. It also suggests China’s attempts to become more food-secure are bearing fruit (pardon the pun).

Global production has reached new records, to be sure – but so has global consumption. And according to the USDA’s 2021 Wheat Outlook, consumption is projected to outpace growth in supplies and lead to even tighter wheat stocks. One of the byproducts of this situation is an increase in shipping costs for wheat. According to the International Grains Council, for instance, since November 2020, freight rates for wheat exports have increased 40 percent.

The real proof is in how even wheat exporters are prophylactically implementing protectionist trade policies. Russia, for example, began taxing wheat exports in February 2021 to ensure stable prices for its domestic supply. Ukraine and Kazakhstan have also implemented wheat export limits. On the flip side, countries like Turkey, Pakistan, and Morocco have all eliminated or significantly reduced wheat import tariffs. For countries like Turkey and Pakistan, whose currencies continue to tumble to new lows on the dollar and who import large amounts of wheat, it is not hyperbole to suggest that a sharp increase in global wheat prices could be regime-threatening. Hell hath no fury like a hungry mob.

And all that is without mentioning the ongoing drought in South America and the impact that might have on already tightening global wheat supplies, as well as the sharp increase in global fertilizer prices which could lead to decreased yields. (To read our previous work on fertilizer prices, click here.)

The UN’s FAO is concerned but not worried. According to FAO projections, even though stocks will decline in 2021/22, the world will still see “a comfortable supply situation overall.” The FAO bases that optimism on good weather conditions for the winter wheat crop in the northern hemisphere, as well as above-average sowing in Russia and Ukraine. If the pandemic has taught us anything, however, it is that nothing should be taken for granted. If all goes well, wheat prices could stabilize or even decline in the year ahead – but due to the impact of the last two years, there is not a lot of room for error should the weather not cooperate, or a new strain of COVID-19 lead to renewed shutdowns. All of which are reasons to watch wheat prices very closely. Even if they don’t directly affect your bottom line, they are a key bellwether for the global economy and for political stability at the macro level.