Income-seeking investors often compare midstream energy infrastructure with utilities. Both own long-lived infrastructure assets dedicated to delivering energy to customers. Both tend to be regarded as yield-generating investments and are subject to considerable regulatory oversight on rate-setting.

But the energy transition is impacting each sector very differently.

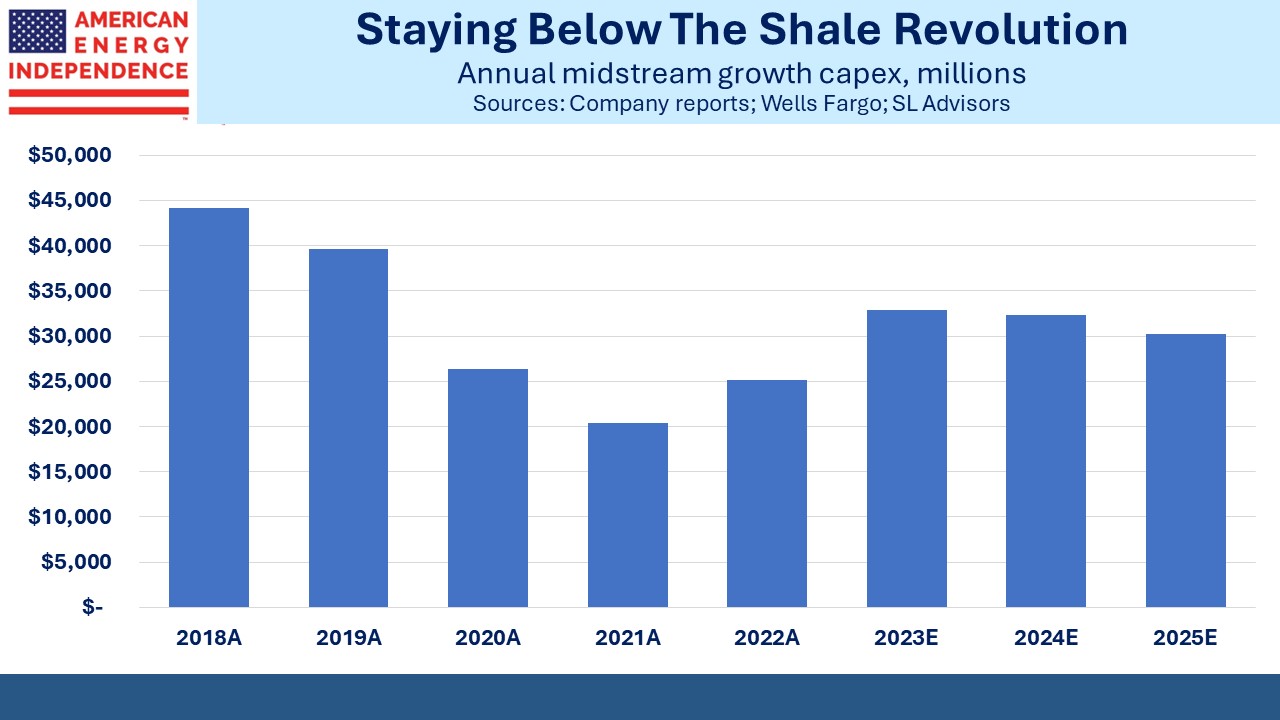

Midstream growth capex peaked during the shale revolution when new pipelines were being built to help exploit new sources of oil and gas released through fracking and horizontal drilling. The subsequent abundance was good for consumers but not investors. Financial discipline returned. The pandemic and the brief but sharp collapse in prices further cemented the energy sector’s focus on financing only those projects that would clearly be profitable.

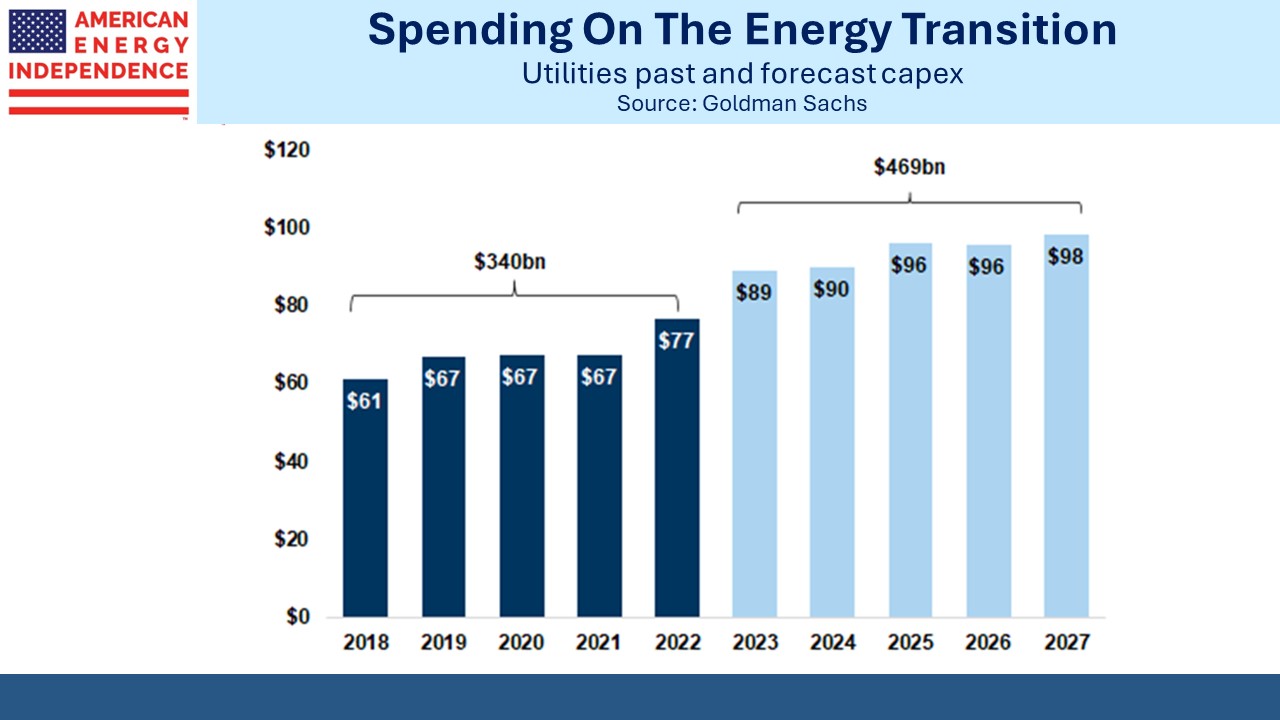

Now utilities are experiencing their own boost in growth capex. They are the sector most responsible for delivering on the promise of electrification using more renewables. This means investing in shorter-lived solar and wind farms along with the high voltage transmission lines to move power to population centers. It means adding more back-up power, either batteries or natural gas, to compensate for the grid unreliability that the increasing share of intermittent power imposes. And sometimes it means phasing out coal-burning power plants before they’ve reached the end of their useful lives.

Elected officials have promised voters that renewables are cheaper than conventional power sources. It’s not uncommon to read that per Kilowatt Hour solar now beats natural gas. This superficial analysis usually omits the cost of back-up power, which ironically is often natural gas.

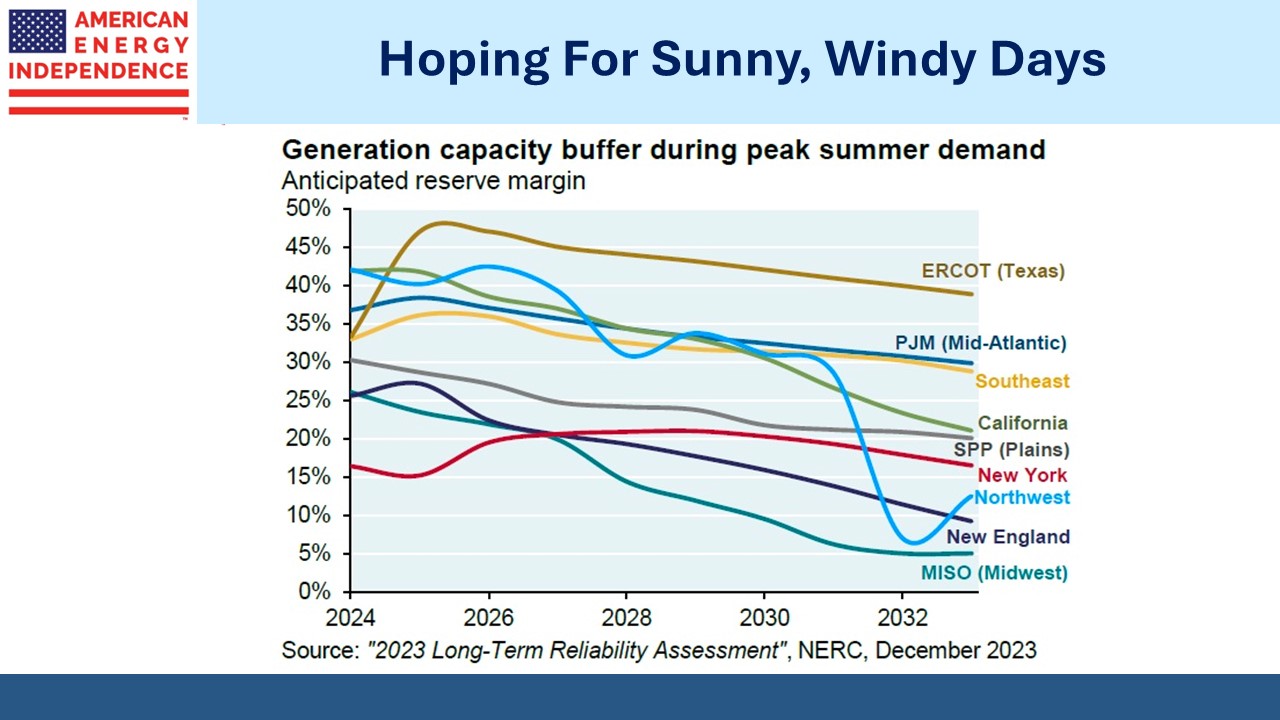

Caught between the higher cost of renewables and political promises of lower costs, grids across the US are gradually reducing their capacity buffer to deal with extreme weather events and substantial loss of power. The MISO system which runs from Minnesota to Louisiana is assessed by the North American Electricity Reliability Association as having the greatest risk of power outages.

Every grid region will experience steadily declining ability to support demand peaks. Power losses because of increased grid reliance on renewables will not sit well with consumers. At times when electricity falls short of the 100% availability that the public expects, the responsibility for explaining why will sit with utilities.

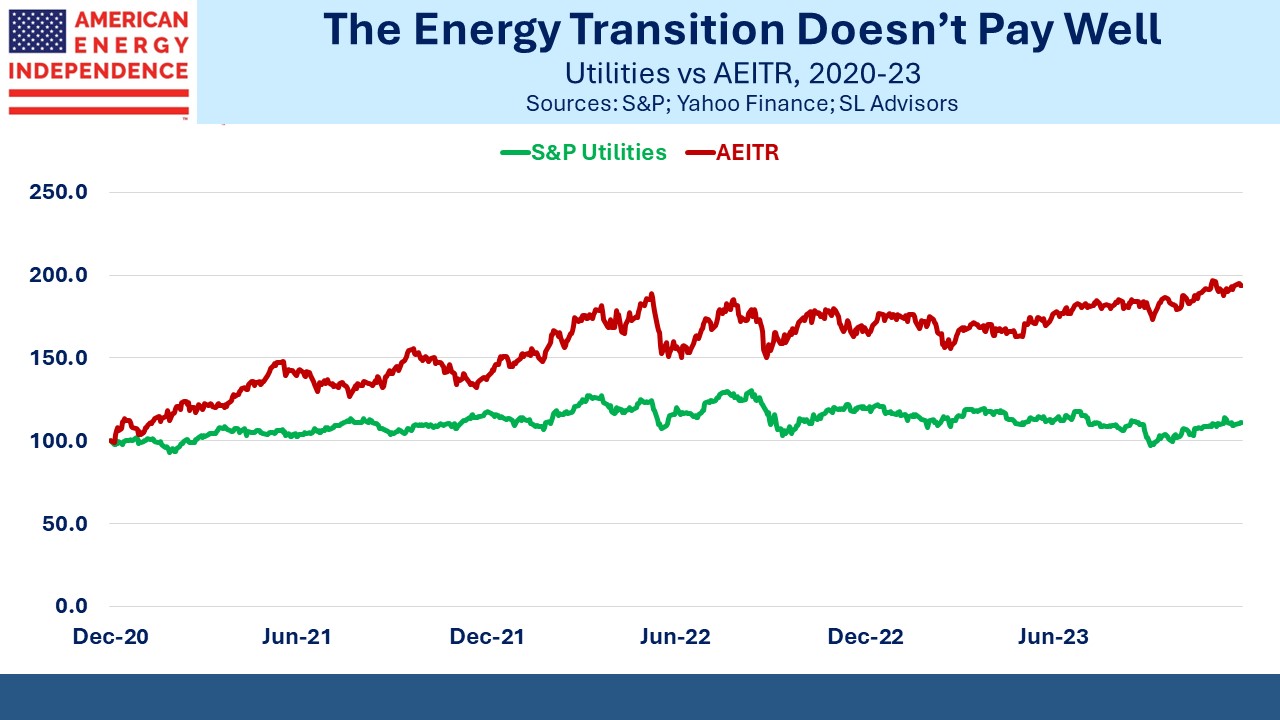

In recent years the market has been reaching the conclusion that investing in the energy transition via utilities isn’t a great bet. They face an increased need to spend to meet unrealistic expectations.

There is much that can go wrong with that unappealing risk/return profile. It’s why the S&P Utilities index has returned only 3.5% pa over the past three years versus the American Energy Independence Index at 24.6% pa.

Whether it’s the S&P Global Clean Energy Index or the losses suffered by offshore wind manufacturers such as Denmark’s Orsted (see Windpower Faces A Tempest), holding equity in companies dedicated to the energy transition has left investors worse off.

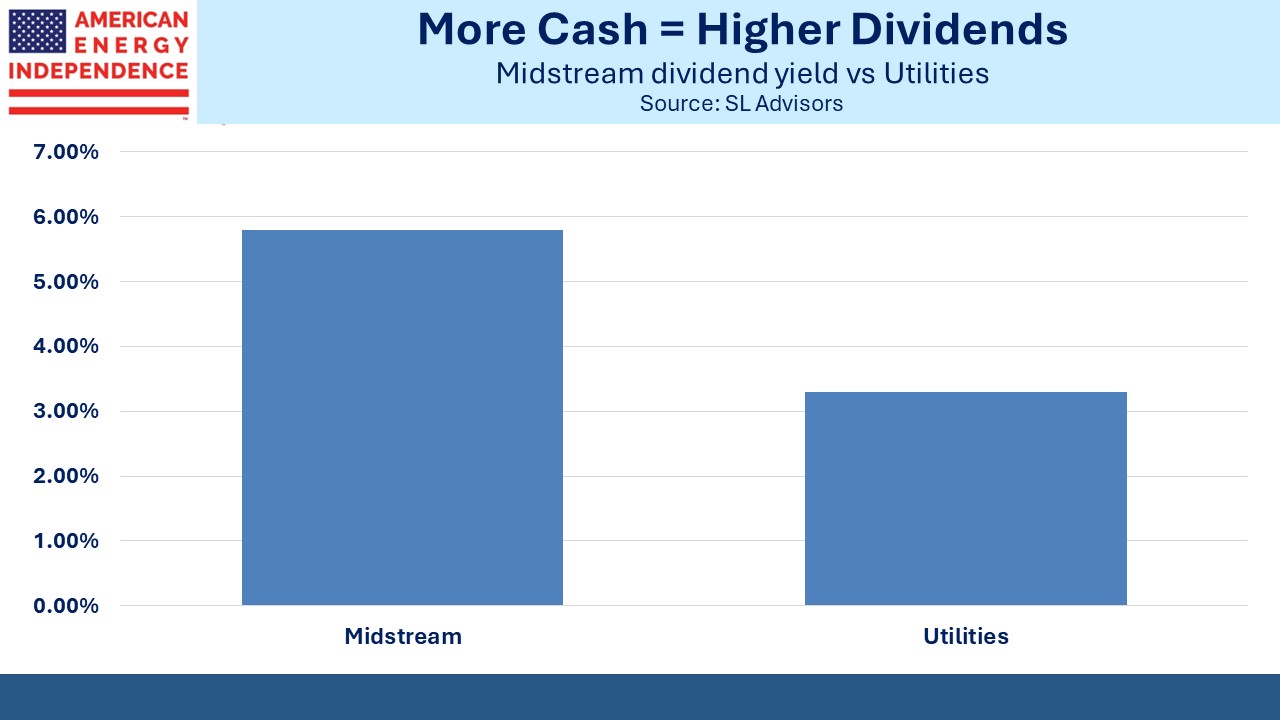

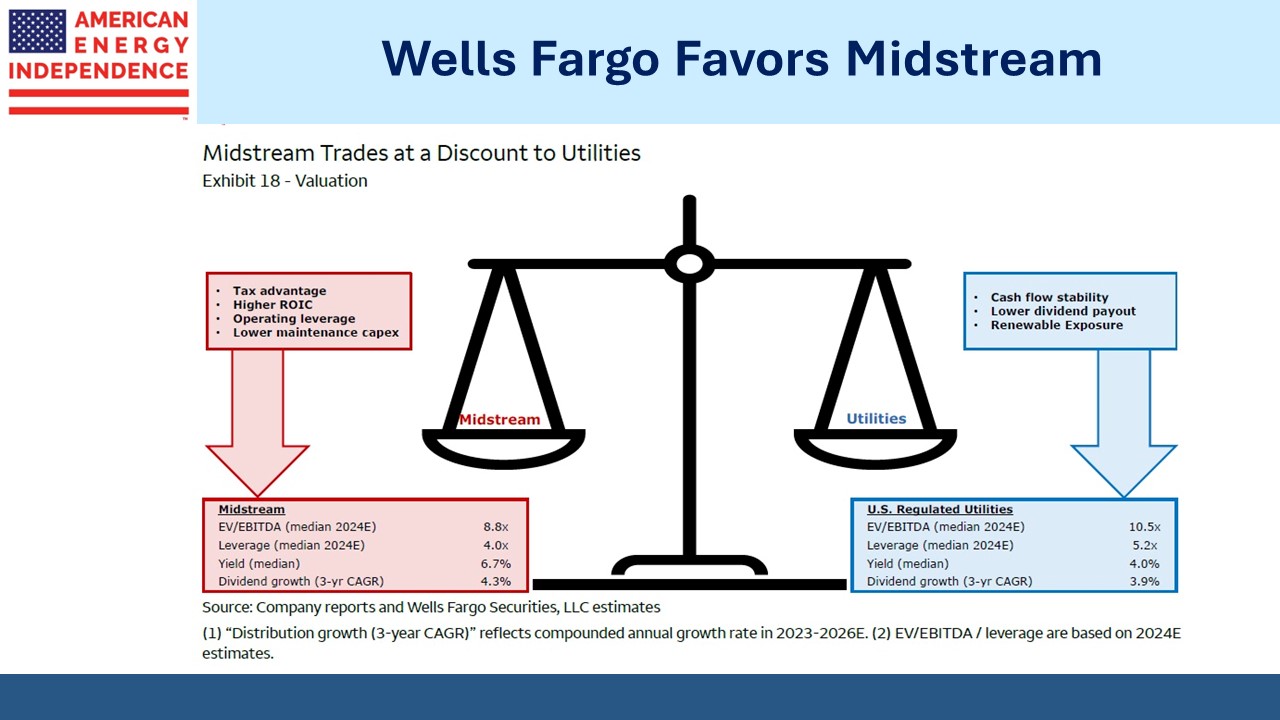

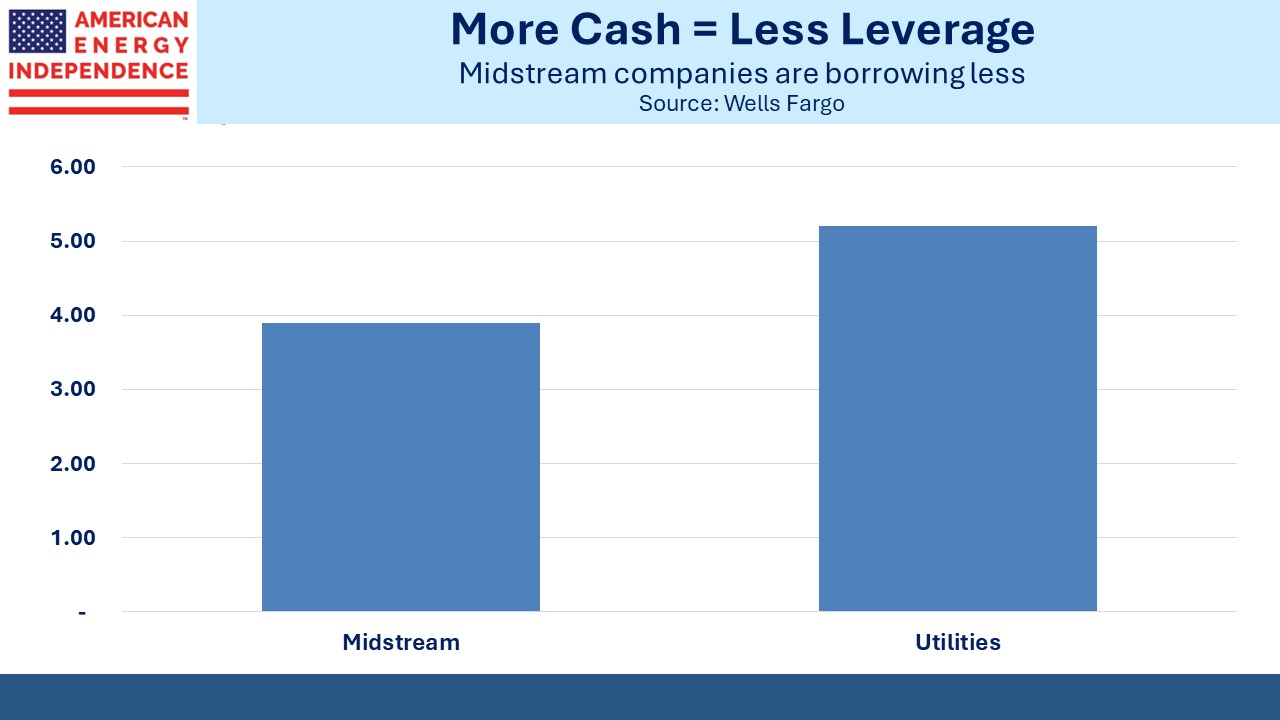

Adding insult to injury, the miserable performance of utility stocks hasn’t made them cheap. Wells Fargo notes the lower EV/EBITDA and leverage of midstream versus utilities along with the higher dividend yield and growth outlook.

Midstream companies have plenty of energy transition opportunities. These include increasing global demand for US LNG along with domestic natural gas back-up for growth in renewables. Then there are substantial tax incentives to develop carbon capture and hydrogen.

But pipeline companies can make decisions to invest in such projects largely based on IRR. They don’t face any political pressure to do so.

By contrast, utilities do face political pressure to deliver the energy transition. Goldman Sachs expects their capex over the next five years to be 38% higher than the past five. Nobody is going to build a new coal-burning power plant (thank goodness) regardless of IRR. But they’ll be dependent on regulators to allow rates that justify prior investment in solar and wind. This is what’s led to the collapse of several offshore wind projects in recent months.

Several years ago, investors feared that oil and gas pipelines would be retired early as the world moved to widespread electrification and renewables. A more realistic outlook has prevailed in recent years that acknowledges the risks facing companies at the forefront of the energy transition.

Shifting the world’s economy to low or no emission energy will be costly. It may be worth it but until politicians are honest about the costs, utilities look to be in a Catch 22.

Last week the Wall Street Journal published an article (see You’ve Formed Your Opinion on EVs. Now Let Me Change It) which concluded with the incorrect statement from Bloomberg NEF that globally, “…EV adoption cut demand for oil by 1.8 million barrels in 2023… thereby avoiding 122 megatons of carbon-dioxide emissions”

This overlooks that China, the world’s biggest EV market, overwhelmingly relies on coal to produce electricity. This is sloppy analysis that’s all too common in the debate about climate change.

The post To Lose On The Energy Transition Buy Utilities appeared first on SL-Advisors.