KEY ASSUMPTIONS

- Income earned in an Exchange Traded Fund (ETF) retains its classification when distributed to investors.

- An investor’s unrealized capital gains in an ETF are not taxed until an investor liquidates his position, or if not liquidated, can be eliminated due to step-up provisions of the federal estate tax.

- Returns of capital are paid out of shareholder equity, which is the equivalent of an ETF’s Net Asset Value (NAV). Returns of capital are not taxed.

- With the exception of qualified dividend income (QDI), which is taxed at a reduced rate, traditional dividends and bond interest distributed by an ETF are taxed at an investor’s ordinary income tax rate.

- Capital Dividends are paid out of an ETF’s NAV and, while not taxable, reduce an investor’s cost basis in an investment.

- Lowering an investor’s cost basis in an ETF increases the capital gain on the shares when the shares are sold.

- The tax rate for long-term capital gains is lower than the tax rate on ordinary income.

2018 SINGLE FILER TAX BRACKETS |

||

|

Income |

Tax |

Capital Gains Rate |

|

$0 – $9,525 |

10% |

0% |

|

$9,526 – $38,600 |

12% |

0% |

|

$38,601 – $38,700 |

12% |

15% |

|

$38,701 – $82,500 |

22% |

15% |

|

$82,501 – $157,500 |

24% |

15% |

|

$157,501 – $200,000 |

32% |

15% |

|

$200,001 – $425,800 |

35% |

15% |

|

$425,801 – $500,000 |

35% |

20% |

|

$500,001+ |

37% |

20% |

SUMMARY

A return of capital is typically considered a less than desirable form of distribution from an ETF because it is drawn from shareholder equity rather a fund’s income. However, if used correctly, paying returns of capital can be a useful strategy to minimize an investor’s taxes on the total return earned by an investment.

People who rely upon their investment portfolios to fund consumption can enhance the tax-efficiency of their spending dollar by consuming returns of capital and indefinitely deferring the recognition of capital gains.

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A RETURN OF CAPITAL AND A TRADITIONAL DIVIDEND

Traditional dividends are distributions to shareholders that an ETF pays out of its income. In contrast, returns of capital are paid out of an ETF’s shareholder equity, or NAV. In simple terms, paying shareholders a return of capital is the equivalent of returning some or all of their investment to them.

The dividends of most real estate investment trusts (REITs) and Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs) contain a component of return of capital due to accounting depreciation, a non-cash charge that reduces taxable income without reducing the amount of cash flow that a REIT or MLP has available for distribution. However, in operating corporations that pay out dividends on a regular schedule, paying returns of capital is typically viewed as undesirable.

Operating companies hate to decrease their dividend payouts because it usually signals problems with the company’s main business. Returns of capital are typically considered an inferior way for operating companies to pay dividends because they are essentially giving shareholders back some of their own money. Using return of capital to make a dividend payment may mean an operating company didn’t earn enough profit to provide enough cash for the dividend payment.

RETURN OF CAPITAL OFFERS TAX BENEFITS

In the case of an ETF, however, a sophisticated fund manager can use return of capital to lower the taxes an investor incurs on the total return generated by the ETF.

With the exception of QDI, which is taxed at a reduced rate, traditional dividends from stocks and interest paid from fixed-income securities are taxed at the investor’s ordinary tax rate. In 2018, ordinary income tax brackets range from 10% to 37%, depending on the individual’s annual income. Short-term capital gains, or profits on investments held less than one year, are also taxed at the investor’s ordinary tax rate.

However, long-term capital gains, the profits on investments held longer than one year, are taxed at lower rates, either 0%, 15%, or 20%, depending on the investor’s taxable income and filing status.

Returns of capital are not taxed at all because they aren’t income or profits from the investment, but rather a return of an investor’s own money.

For instance, if an investor bought 1,000 shares of an ETF called ABC Fund at $100 per share, the initial capital investment would be $100,000. If the investment paid an annual income distribution of $7,000. That income would be taxed at the investor’s ordinary tax rate.

However, assume that $7,000 distribution was a combination of $3,500 income from the investment, either dividends or interest, and $3,500 return of capital. The investor would only pay taxes on the $3,500 of income because return of capital isn’t taxed. This would lower the amount of the distribution that is taxable in one way or another by 50%. The total distribution is still the same, but the tax consequences differ. Furthermore, by favoring an investment strategy that can produce capital growth using a structure than minimizes realized capital gains, the investor can defer taxes on capital growth and even, potentially, avoid such taxes completely.

RETURN OF CAPITAL LOWERS THE INVESTMENT’S COST BASIS

Distributions that include a return of capital reduce an investor’s cost basis in the investment.

Returning to the example above, the investor’s cost basis for the purchase of shares of ABC Fund was $100,000 (1,000 shares times $100 per share). The annual distribution from that investment was $7,000, with $3,500 constituting return of capital. The distribution would therefore lower the investor’s cost basis by $3,500, bringing it down to $96,500 ($100,000 minus $3,500).

For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume the investor is the only shareholder of ABC Fund and that during the period covered by the distribution, ABC Fund generated investment income of $3,500 and experienced $3,500 of unrealized capital gains in its investment securities. In other words, let’s assume ABC Fund increased in value by a total of $7,000 during the period.

While funds generally must distribute investment income annually, ABC Fund has some flexibility in choosing how to fund its $7,000 distribution for the period. One approach would be to sell its appreciated securities and distribute $3,500 in investment income and $3,500 in capital gains to investors. With this approach, the entire distribution would be taxable either as income or capital gains. Alternatively, ABC Fund could elect to retain its appreciated securities and instead distribute $3,500 in investment income and a $3,500 return of capital (either from cash on hand or by selling unappreciated securities). With the latter approach, the investor would not pay tax on the $3,500 return of capital but would instead experience a reduction in his cost basis from $100,000 to $96,500.

On a pre-tax basis, the investor’s position is unaffected by how ABC Fund chooses to fund the distribution. The investor began with a $100,000 investment, which grew by $7,000 during the period, and is now receiving a $7,000 distribution. The only difference between the two approaches concerns the tax treatment of the distribution. In the first instance, the entire distribution is taxable either as investment income or capital gains. In the second instance, ABC Fund enables the investor to defer taxes on unrealized capital gains by instead funding that portion of the distribution out of paid-in capital.

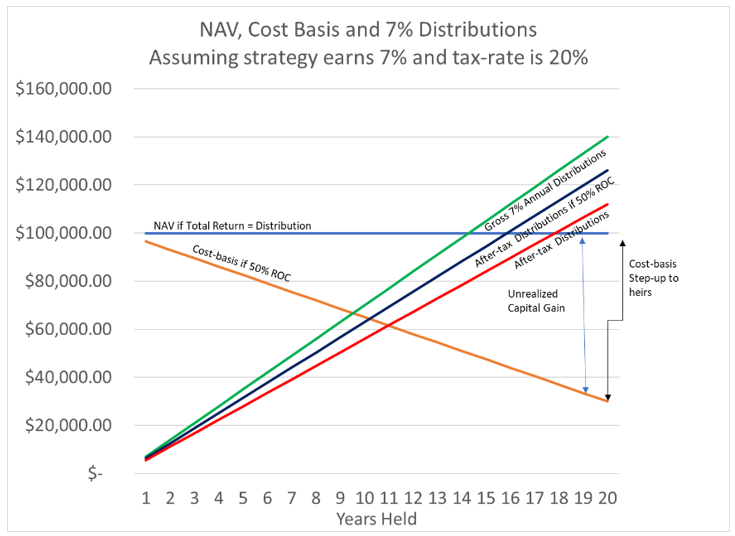

The following graph illustrates the effect by showing a $100,000 initial investment and holds the total return, distribution and tax rate constant to isolate the benefit of deferral.

If distributions are comprised 50% of return of capital, the investor’s cost basis declines steadily over the next 20 years, after-tax distributions increase and the investor can defer the realization of capital gains potentially indefinitely.

RETURN OF CAPITAL CAN DEFER REALIZATION OF CAPITAL GAINS

One of the benefits of the ETF structure is that it offers the potential to defer the realization of capital gains through the creation/redemption process of ETF shares. When ETF shares are created, they are sold to a special broker-dealer called an authorized participant (AP), who then sells them on the secondary market. Conversely, when ETF shares are redeemed, an AP redeems ETF shares that it has acquired on the secondary market.

Transactions between APs and ETFs generally do not involve cash. When an AP creates new ETF shares, it exchanges a basket of securities, called a creation unit, for shares of the ETF. The creation unit consists of all the securities that are represented by one share of the ETF. For example, in the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust (SPY), one share of the ETF represents one share of each of the 500 companies in the S&P 500 Index. To create shares of SPY, an AP would buy shares of each of the 500 companies and exchange them with the ETF for shares of SPY. The process works in reverse when an AP redeems ETF shares, with the AP receiving the creation unit in exchange for ETF shares.

This is called an in-kind trade, since shares are swapped for shares. Because cash is not exchanged, the Internal Revenue Service doesn’t consider this a taxable transaction. This means that in a redemption, an ETF can “in-kind out” appreciated securities for ETF shares without realizing capital gains on the appreciated securities. In contrast, since mutual funds generally sell and redeem fund shares for cash, they may have to sell appreciated securities for cash in order to fund redemptions, thereby generating capital gains inside the fund that must be distributed to shareholders. The in-kind creation/redemption process is the foundation for the much-noted tax efficiency of ETFs compared to mutual funds.

While the ETF structure offers the potential to minimize realized capital gains inside the fund, investors may still incur capital gains when they sell their fund shares. Consider the example above in which ABC Fund pays out a $7,000 annual distribution with 50% of it consisting of return of capital. If the investor holds ABC Fund’s shares for two years and receives a $7,000 distribution each year for a total of $14,000, $7,000 of that would be taxed as ordinary income and $7,000 would be return of capital and not taxed. This would lower the investor’s cost basis to $93,000 ($100,000 minus $7,000 in return of capital over two years).

If over that period, the shares of ABC Fund earn $7,000 in investment income and experience $7,000 of unrealized capital gains, the investment would still be worth $100,000. Consequently, if the investor decides to sell his shares in ABC Fund at that point, he would incur a capital gain of $7,000 ($100,000 less his adjusted cost basis of $93,000).

By paying out a return of capital rather than selling appreciated securities to fund its annual distribution, ABC Fund avoids realizing short-term capital gains inside the fund on its appreciated securities and allows the investor to defer taxes on his investment appreciation until such time as he sells his shares in ABC Fund. If he holds his shares in ABC Fund for more than a year, he receives long-term capital gains treatment and pays a lower tax rate.

LONG-TERM BENEFITS OF USING RETURN OF CAPITAL

The investor can permanently avoid capital gains taxes on his unrealized gains by not selling the shares and leaving the investment in ABC Fund to his heirs. Under the federal estate tax, when beneficiaries receive property from an estate, the cost basis in the property is “stepped up” to its current value. Thus, if the shares in ABC Fund are worth $100,000 when the investor dies, the cost basis for the beneficiaries becomes $100,000—even if the investor’s adjusted cost basis had been reduced to $93,000. This step up in the cost basis of the shares has the effect of eliminating taxes on the investor’s $7,000 of unrealized capital gains. The beneficiaries only pay taxes on share price appreciation above the new cost basis of $100,000.

CONCLUSION

Returns of capital are considered an inferior way to pay out corporate dividends because they do not come out of company profits and instead represent the return of an investor’s original investment capital back to the investor. In this context, returns of capital may indicate a company is generating insufficient earnings to fund its dividend.

However, in an ETF, a sophisticated fund manager can strategically use return of capital in a distribution to defer and potentially eliminate taxes on unrealized capital gains. Simply stated, money is fungible and investors who need to spend money should consider investment strategies and distribution policies that maximize the tax efficiency of their consumption. ETFs that incorporate return of capital as part of a distribution plan may be beneficial to investors seeking to defer or eliminate taxes on capital appreciation.

Written by Lawrence Carrel