What if the Fed can’t hike rates? It’s an interesting question and one we delved into in Part 1 – “Fed Won’t Hike Rates As Much As Expected.”

With the January FOMC meeting now behind us, we have much better visibility about the Fed’s intentions.

“With inflation well above 2 percent and a strong labor market, the Committee expects it will soon be appropriate to raise the target range for the federal funds rate.” – FOMC

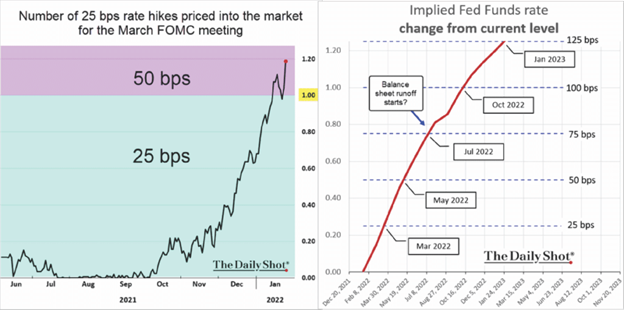

The post-meeting statement from the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) did not provide a specific time frame for increasing the overnight lending rate. However, there are many indications that such could happen as soon as the March meeting. As shown in the charts below courtesy of “The Daily Shot.”

About the Fed’s “Quantitative Easing” program, the FOMC noted its bond-buying program would fall to just $30 billion in February, down from $120 billion a month in 2021. In addition, the Fed will terminate purchases in March consistent with an increase in interest rates.

Interestingly, there was no specific indication of when the Fed might start to reduce its nearly $9 trillion balance sheet. The most significant risk to equities is the contraction of liquidity from “Quantitative Tightening.“ Such is what preceded the market rout in 2018.

However, while the Fed is intent on hiking rates and reducing accommodation, I am reminded of an age-old proverb:

“The road to hell is paved with good intentions.”

While the Fed may intend to hike rates and taper their balance sheet, the real question is, “can they?”

The Fed’s Inflation Trap

There are two primary considerations for the Fed as we progress into 2022. As noted in part-1, the reversal of liquidity is problematic.

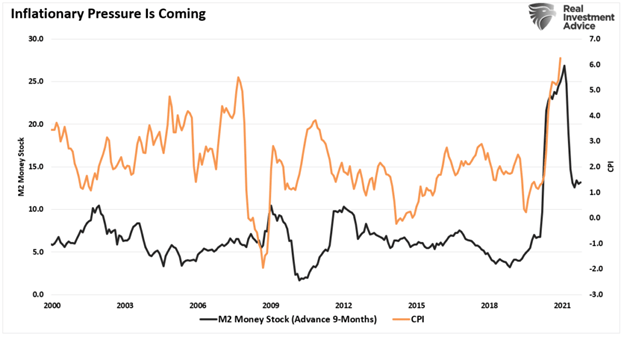

As recently discussed, “deflation” is the overarching threat longer-term. However, in the short term, the flood of liquidity into the system created, as expected, surging inflationary pressures. With the measure of money in the system, known as M2, skyrocketing, the resulting surge in inflation is not surprising.

Furthermore, in a previous Bloomberg interview, Larry Summers stated:

“There is a chance that macroeconomic stimulus on a scale closer to World War II levels will set off inflationary pressures of a kind not seen in a generation. I worry that containing an inflationary outbreak without triggering a recession could be even more difficult now than in the past.”

As we indicated in part-1, inflation surged almost exactly 9-months after the massive infusions of fiscal policy. So while many, including the Fed, suggest inflation is problematic, M2 indicates disinflation remains the most likely outcome.

The current surge in inflationary pressures pushed the Fed to hike rates and reduce its bond-buying program. However, they could be acting precisely at the wrong time. In 1998, Alan Greenspan started aggressively hiking rates to combat an “inflation threat” that never materialized. The resulting consequence was the implosion of the “dot.com” bubble.

However, such is why inflation isn’t the most significant risk limiting the Fed.

The Fed “Instability” Trap

“When it comes to Federal Reserve policy, investors are focused on the wrong question. Investors continue to agonize over when the Fed will trim its $120 billion in monthly asset purchases. A more important question is when will the Fed raise interest rates. More important still: whether the Fed actually can raise rates.” – Joe LaVorgna, Barron’s

That is a critical question. As discussed previously, the Fed is dependent on “stability” to keep the financial “house of cards” from collapsing.

With the entirety of the financial ecosystem heavily dependent on debt, the “instability of stability” is the most significant risk to the Fed.

After more than 12-years of the most unprecedented monetary policy program in U.S. history, the Fed realizes there are significant risks in the financial system. The behavioral biases of individuals remain the most serious risk facing the Fed.

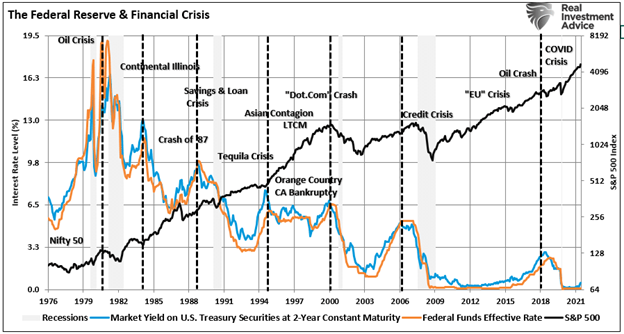

The Fed’s actions have repeatedly led to adverse outcomes throughout history despite the best of intentions.

- In the early 70’s it was the “Nifty Fifty” stocks,

- Then Mexican and Argentine bonds a few years after that

- “Portfolio Insurance” was the “thing” in the mid -80’s

- Dot.com anything was a great investment in 1999

- Real estate has been a boom/bust cycle roughly every other decade, but 2007 was a doozy

- Today, it’s real estate, FAANNGT, debt, credit, private equity, SPAC’s, IPO’s, “Meme” stocks…or rather…”everthing.”

“If easy money is the bedrock of valuations and the Fed is getting ready to shift the bedrock, investors best pay attention to market forecasts and how the Fed ultimately acts.“ – Michael Lebowitz

With the Fed now reversing monetary accommodation, the question is how long before something breaks.

Trapped At Zero?

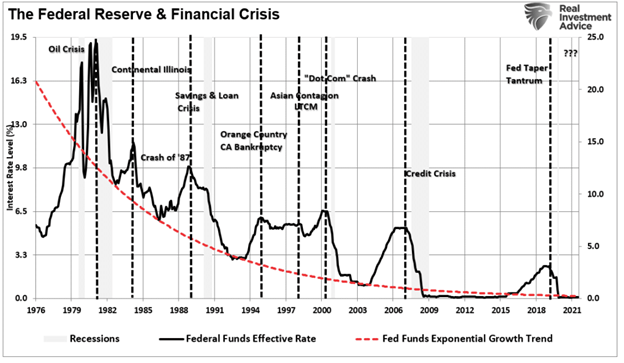

Looking at the long-term history of the overnight lending rate versus its exponential growth trend, it tells an interesting story.

The rise and fall of stock prices have very little to do with the average American and their participation in the domestic economy. Interest rates are an entirely different matter. As discussed in “Rates Do Matter:”

In the short term, the economy and the markets (due to the current momentum) can DEFY the laws of financial gravity as interest rates rise. However, as interest rates increase, they act as a “brake” on economic activity. Such is because higher rates NEGATIVELY impact a highly levered economy:

- Rates increases debt servicing requirements reducing future productive investment.

- Housing slows. People buy payments, not houses.

- Higher borrowing costs lead to lower profit margins.

- The massive derivatives and credit markets get negatively impacted.

- Variable rate interest payments on credit cards and home equity lines of credit increase, reducing consumption.

- Rising defaults on debt service will negatively impact banks which are still not as well capitalized as most believe.

- Many corporate share buyback plans and dividend payments are done through the use of cheap debt.

- Corporate capital expenditures are dependent on low borrowing costs.

- The deficit/GDP ratio will soar as borrowing costs rise sharply.

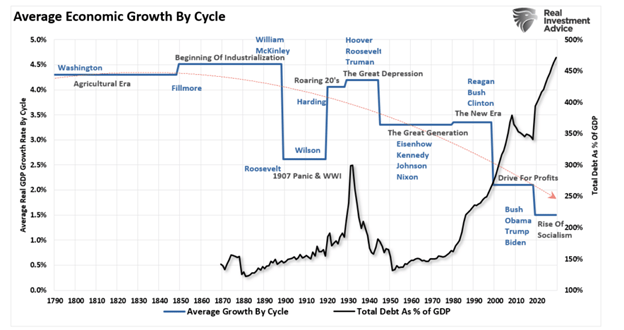

The debt problem exposes the Fed’s risk and why they continue to look for excuses NOT to hike rates. (Like “full employment” even though jobless claims are at record lows.) However, given economic stability was not achieved in the last decade, it is doubtful the withdrawal of monetary accommodation will be “risk-free.”

The evidence is quite clear that surging debt and deficits inhibit organic growth, and the massive debt levels are sensitive to increases in interest rates.

Wash, Rinse, Repeat

As we argued in part one, we believe the Fed’s ability to hike rates from the zero bound is minimal before “financial stability” becomes an issue.

The primary bullish argument for owning stocks over the last decade is that low-interest rates support high valuations.

If that is the case, higher rates will undermine the financial markets.

With exceptionally high market valuations, Fed rate hikes historically led to events that devastated investors. Those events created the Fed’s repetitive cycle of monetary policy.

- Monetary policy drags forward future consumption leaving a void in the future.

- Since monetary policy does not create self-sustaining economic growth, ever-larger amounts of liquidity are needed to maintain the same level of activity.

- The filling of the “gap” between fundamentals and reality leads to economic contraction.

- Job losses rise, wealth effect diminishes, and real wealth reduces.

- The middle class shrinks further.

- Central banks act to provide more liquidity to offset recessionary drag and restart economic growth by dragging forward future consumption.

- Wash, Rinse, Repeat.

Conclusion

“Financial markets’ sensitivity to monetary policy has never been higher. The Fed’s balance sheet doubled since the end of the last financial crisis and is now 40% of gross domestic product. By buying massive amounts of bonds, the Fed lowered rates and used asset prices, like stocks, as the primary tool for monetary policy. That’s through the so-called wealth effect, or the tendency for consumers (two-thirds of GDP) to spend more as their assets grow.” – Joe LaVorgna

Therein lies the problem.

If the Fed tightens, the existing debt pile becomes more expensive to service, and stocks fall, hampering consumer confidence and economic growth.

On the other hand, if the Fed doesn’t tighten, debt across households, companies, and the government will continue to grow, making it more challenging for the Fed to act in the future

The Fed has put itself in a box that will be difficult to get out of, especially if economic growth slows, which is almost a certainty.

As we concluded previously:

Unfortunately, we doubt the Fed has the stomach for “financial instability.” As such, we doubt they will hike rates as much as the market currently expects.