Before there were Saudis – there were Texans. In 1948, U.S. oil production and reserves accounted for 64 percent and 34 percent of the global total. Texas was the largest U.S. producer by far, accounting for 45 percent of total U.S. production. The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, aka OPEC, was part modeled after the Texas Railroad Commission, which set quotas for Texas oil production during those heady times. Over the next two decades, however, rising global demand was more than Texas could handle. On the eve of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, The U.S. share of global production declined to 22 percent and the U.S. share of global reserves declined to 7 percent. To meet domestic demand, the US was importing almost one-third of total consumption.

Source: https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=pet&s=mttimus1&f=a

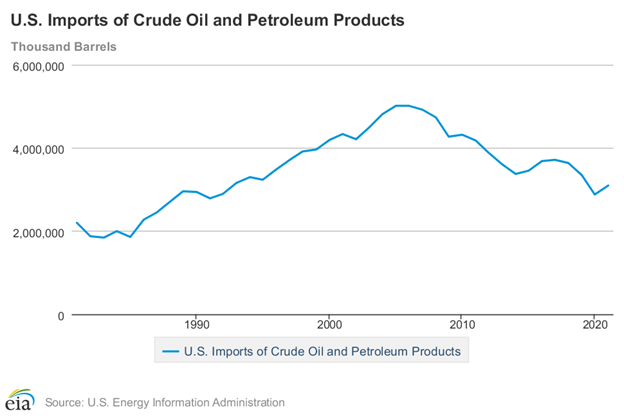

For the next 30 years, U.S. oil imports climbed steadily, peaking in 2005 at just over 13,700 barrels per day. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, energy security became the paramount geopolitical issue for policymakers in Washington. During this brief unipolar moment, the U.S. was not concerned with the rise of China or Russian revanchism, but with where it got its oil. Venezuela, Iran, Iraq – it is not a coincidence that the flotsam of U.S. foreign policy since 1991 is littered with oil-rich states. Beneath the surface, however, something more important was happening. The U.S. government subsidized drilling for non-conventional gas throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Between 1978 and 2007, the U.S. Department of Energy spent $24 billion on fossil fuel research. Billions more were made available via various tax credits for intrepid wildcatters

Source: https://www.eia.gov/maps/images/shale_gas_lower48.pdf

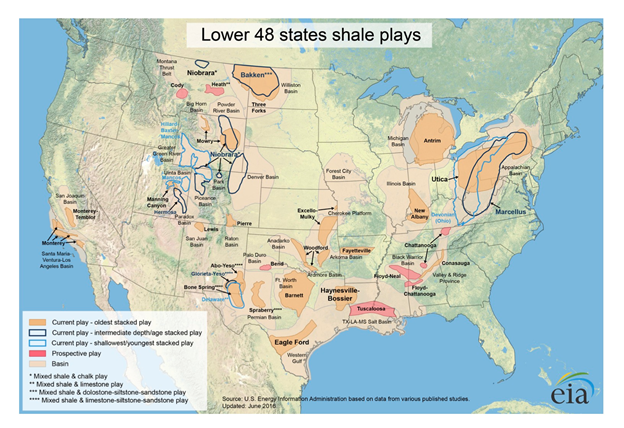

The result, of course, was the Shale Revolution. By combining hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) with horizontal drilling, the U.S. figured out how to increase oil and natural gas production from tight formations and regained its former position as a global energy superpower. The Shale Revolution would not have happened if it were not for the dogged, persistent, and risky attempts by individuals and companies to figure how to capitalize on U.S. natural resources – but all of it would likely have been for naught if not prioritized and subsidized by the U.S. government. And it is that lesson that points toward a similar opportunity hiding in plain sight: U.S. mining of strategic minerals.

Take the poorly named class of minerals known as Rare Earth Elements (REEs) – poorly named because they are not rare at all. Indeed, from the 1960s-1980s, the U.S. was the

global leader in the mining, production, and development of REEs. The thing about REEs is that they are expensive to mine, and especially expensive (perhaps impossible?) to mine in an environmentally sustainable fashion. When the U.S. doubled down on deregulation and supply side Reaganomics in the 1980s to combat stagflation, companies began to look abroad for cheaper labor and regimes less concerned about the environment. China decided to become the global REE superpower. Today, U.S. import reliance for REEs is over 90 percent, with the bulk coming from China, and Estonia and Malaysia serving as alternative import sources. Quietly, the U.S. has ramped up REE production in the last 4 years, going from 0 to 43,000 tons from 2017-2021.

Rare Earths U.S. Production

Source:https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2022/mcs2022.pdf

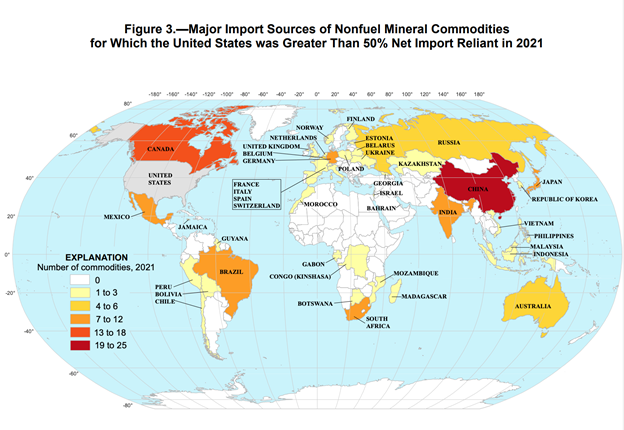

REEs, however, are hardly the only mineral commodity the U.S. has become dependent on imports for. The reason REEs captured the U.S. imagination early on was because back in 2010, China blocked exports of REEs to Japan – in hindsight, a signpost that globalization was at or near its zenith. In 2018, the Trump administration identified 35 critical minerals that posed a threat to U.S. national security, and the Biden administration added an additional 15 critical minerals of their own in a February 2022 update to Trump’s list. Some of the minerals you’ve probably never heard of – like dysprosium, or germanium. Others are as common as it gets – like aluminum and nickel. All are critical to the U.S. economy – and most have been sorely lacking in investment for decades.

Source: https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2022/mcs2022.pdf

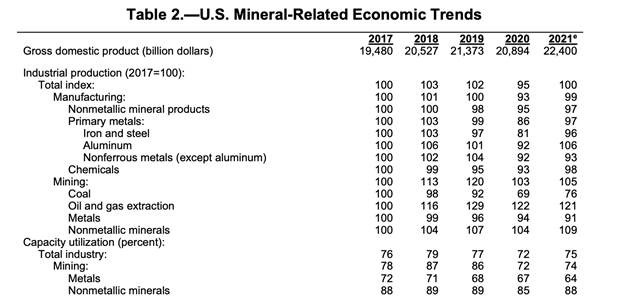

If you look closely at the USGS chart above, you’ll notice that U.S. production of certain things has increased markedly. Oil, natural gas, nonmetallic minerals, and aluminum are all being produced well above the levels they were at in 2017. But there are other areas where the U.S. is seriously lagging. The most glaring and controversial, of course, is coal – and if you missed our look at coal and why it is poised to outperform over the next few years despite all those EV commercials you saw during the Super Bowl, you can click here. But look at the line for metals as well – reflecting a 9 percent decline in the mining of metals. That is because the U.S. continues to import many of these nonfuel mineral commodities from abroad – and from geopolitically risky areas like China and Russia.

Source: https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2022/mcs2022.pdf

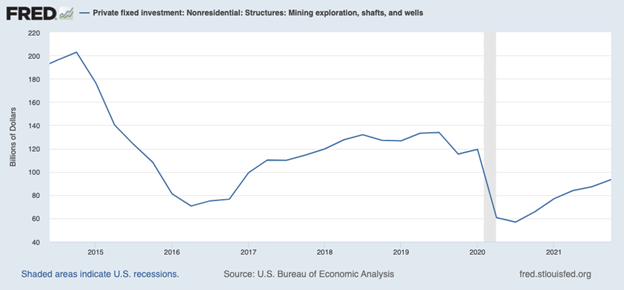

The U.S. cannot produce all the mineral commodities upon which it is dependent on imports – cobalt, for example, is the sole province of the Democratic Republic of Congo, which probably indicates its future as a key mineral of the future will be eclipsed as soon as scientists figure out a workable substitute. But the U.S. is relatively well-endowed with many of the mineral commodities it is importing from abroad, and even the ones the U.S. doesn’t have, it can source from places far less challenging than Russia, China, or even South Africa. The U.S. mining industry, however, has barely been awoken from its slumber. The chart below shows private fixed investment in mining exploration and structures. The data is skewed because it includes oil and natural gas – which you can see fell off a cliff in 2014 when oil prices tanked. But it is also a good proxy for understanding just how early we are in the rebirth of U.S. mining.

As with the semiconductor in the 1950s, which U.S. government and military demand subsidized, and as with shale in the 1980s and 1990s, which U.S. research funds and tax credits subsidized, the U.S. mining industry stands to enjoy the full support of the U.S. federal government. The Biden administration, which is relatively environmentally conscious as U.S. governments go, is bragging to anyone that will listen about the billions it is awarding to companies establishing full end-to-end supply chains for critical minerals. Remarkably, hard rock mining on public lands – which includes things like gold, silver, copper, uranium, and lithium – is still governed by the General Mining Law…wait for it…of 1872. The Biden government announced in February that the Department of the Interior would be working hard to reform those laws to “promote the sustainable and responsible domestic production of critical minerals.” 1872!

In June 2021, the White House released a 100-day review of U.S. supply chains. It is an impressive 250-page document spanning everything from semiconductors to pharmaceuticals – but tucked in the prose is a clarion call for the U.S. mining industry. The top key area the report identifies as where the U.S. government can play a more active role is in “creating 21st century standards for the extraction and processing of critical minerals.” The report calls out lithium, cobalt, nickel, and copper in particular, but also makes clear that the Federal government will do everything in its power to reduce the time, cost, and risks associated with mining in the future. Such a transformation won’t happen overnight, and it will take decades – but think of the U.S. mining industry as where the shale industry was in the 1980s, except this time with geopolitical tailwinds and a commodity super cycle nigh.