Article I of the U.S. Constitution gives Congress the “…Power to lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises…” Congressional control over tariffs has never been so strong since.

The Reciprocal Trade Agreement Act of 1934 granted President Roosevelt the authority to adjust tariffs and to negotiate bilateral trade agreements without prior congressional approval. Other legislation increased the Administration’s control over trade, including the Trade Act of 1974 which allowed the President to impose a 15% tariff if imports threatened national security. There’s much to recommend a single decision maker heading up such negotiations. It should lead to more predictable, less capricious discourse than one requiring congressional approval. For decades, it’s how the U.S. has conducted trade negotiations, and it’s broadly worked.

In recent months, President Trump has demonstrated the full range of options afforded a president to manage trade. Updates on the progress of negotiations with China have been responsible for much of the recent market volatility.

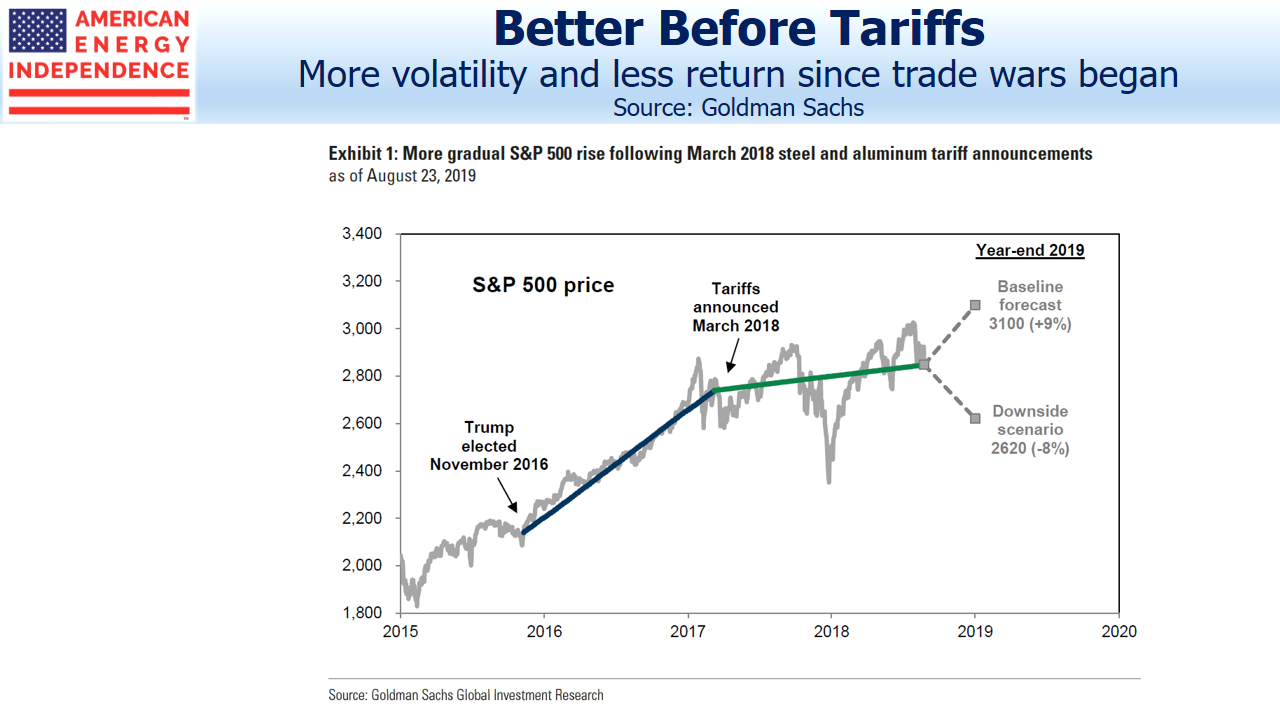

An interesting chart from Goldman Sachs divides the three year performance of the S&P500 into two periods – a steady uptrend that prevailed from Trump’s surprise election until the first imposition of steel tariffs early last year, followed by a modest rise punctuated by higher volatility.

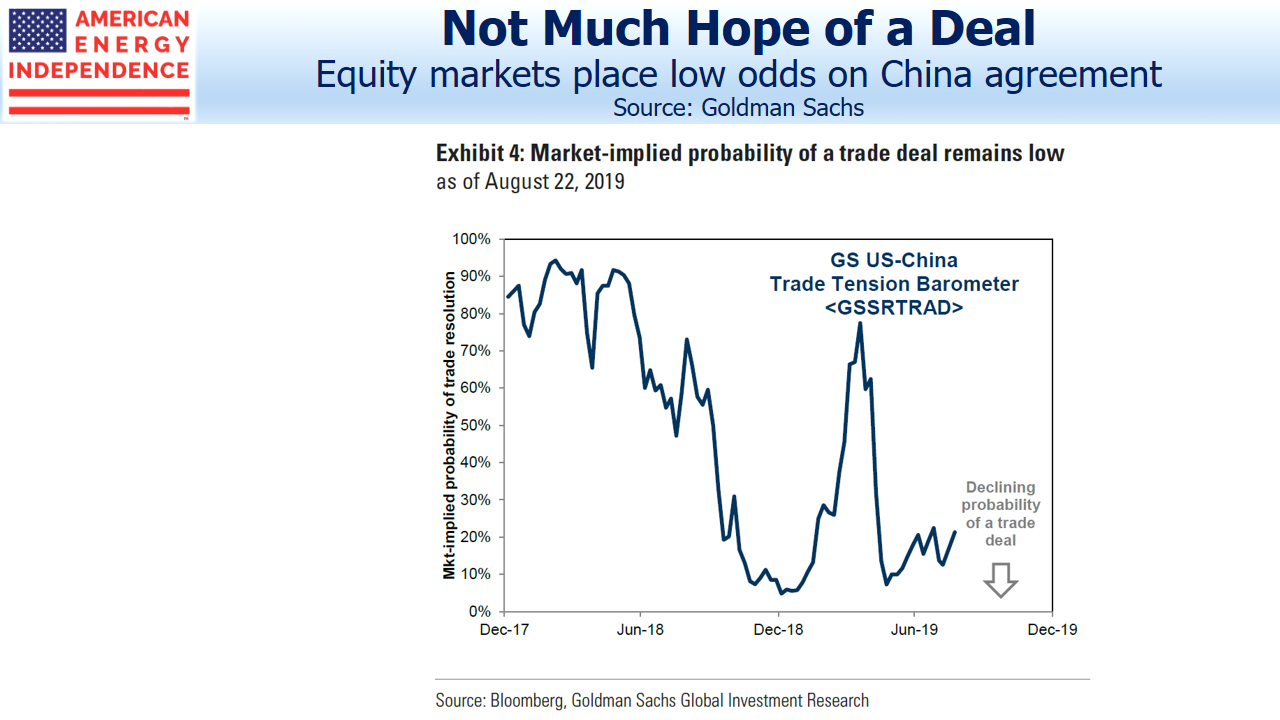

A second Goldman chart infers the market’s estimate of a trade deal by comparing baskets of stocks with sharply different exposure to China. Based on this, market expectations of a trade deal are low, and Goldman duly do not expect one before next year’s election.

Stocks are cheap relative to bonds (see Stocks Offer Bond Investors an Opening). It seems self-evident that Trump’s re-election prospects are better without trade disputes slowing growth, and therefore rational for him to seize a deal. The trade deficit with China is already falling (see Trade Wars: End in Sight), so the opportunity to declare victory and reach agreement is a real one.

Low expectations of an agreement coupled with relatively cheap stocks mean a big rally would follow.

But this analysis isn’t unique, and market participants are looking beyond it. Current pricing of no deal before the election either means Trump won’t seize one, or China will decline to offer a graceful exit from a negotiating strategy that hasn’t yet worked.

This brings us back to the issue of which arm of government should control trade negotiations. There’s much to be said for the current structure. Congress is an unwieldy negotiating partner, and myriad parochial interests could easily derail an almost perfect agreement.

If the low expectations of an agreement turn out to be accurate, calls to restore some of the power originally vested in Congress are likely to grow. Senators from both parties have begun advocating for such a change. If protracted trade uncertainty continues into next year, the odds of legislative action will rise.

Paradoxically, such an outcome could well be bullish if it removed much of the trade uncertainty we’re learning to live with. It’s just hard to assess how much intervening market volatility will be required to provoke lawmakers into action.

The post Hopes for a Trade Deal Slipping appeared first on SL-Advisors.