Last week’s article by Jason Zweig (see Think Before You Fish for Bargains in Chinese Stocks) caught my eye, because it warns against investing in Chinese stocks with the expectation of high GDP growth driving high equity returns. A major reason investors allocate to emerging economies is because they expect that relationship to reward them, although there’s plenty of evidence that it doesn’t work.

Zweig references a 2004 academic paper, (Economic growth and equity returns) which highlighted one important reason: GDP growth can be driven by technological innovation among new, private companies. This does nothing for current investors in public equities. Technological improvements are usually good for consumers but less often for public companies, unless they can exploit their advantage without meaningful competition. The true driver of returns comes from earnings paid out as dividends, and the return on retained earnings that are reinvested back in the business. Chinese public companies have been poor at the latter.

Moreover, the market cap of the MSCI China stock index has grown largely through new equity issuance. So global investors who allocate passively based on market size are induced to increase their China exposure, even though returns on invested capital have been poor.

A 2010 paper from MSCI Barra (Is There a Link Between GDP Growth and Equity Returns?) similarly found no meaningful connection between the two.

Jason Zweig generously concludes that Emerging Markets (EM) investing can still make sense if a country’s market looks cheap. But if GDP growth doesn’t correlate with equity returns, the justification for an EM investment becomes weak. What’s left is a tactical move based on what looks like temporarily weak pricing. That’s not a long-term strategy for most people.

American investors are accustomed to a market with the world’s toughest rules all designed to promote fairness. Protecting investors from bad actors lowers the overall cost of equity, which does boost GDP growth. But it’s easy to assume that America’s standards are global, which they are not. I remember some years ago chatting with a senior regulator from the Reserve Bank of India. I asked him how many insider trading cases are typically prosecuted in a year, to which he replied, “None. There is no insider trading in India.”

Or the hedge fund friend who described how two or three Mumbai-based hedge funds would trade a small local stock amongst themselves, generating volume and a higher price. This would attract, “the New York hedge funds” in search of a rising stock with good liquidity. Having hooked one, the local hedge funds would dump the stock on the naive foreigner (see The Hedge Fund Mirage, page 42).

An emerging market doesn’t mean the participants are unsophisticated — in fact, the comparative absence of rules mandates more highly attuned street smarts than is required in developed markets.

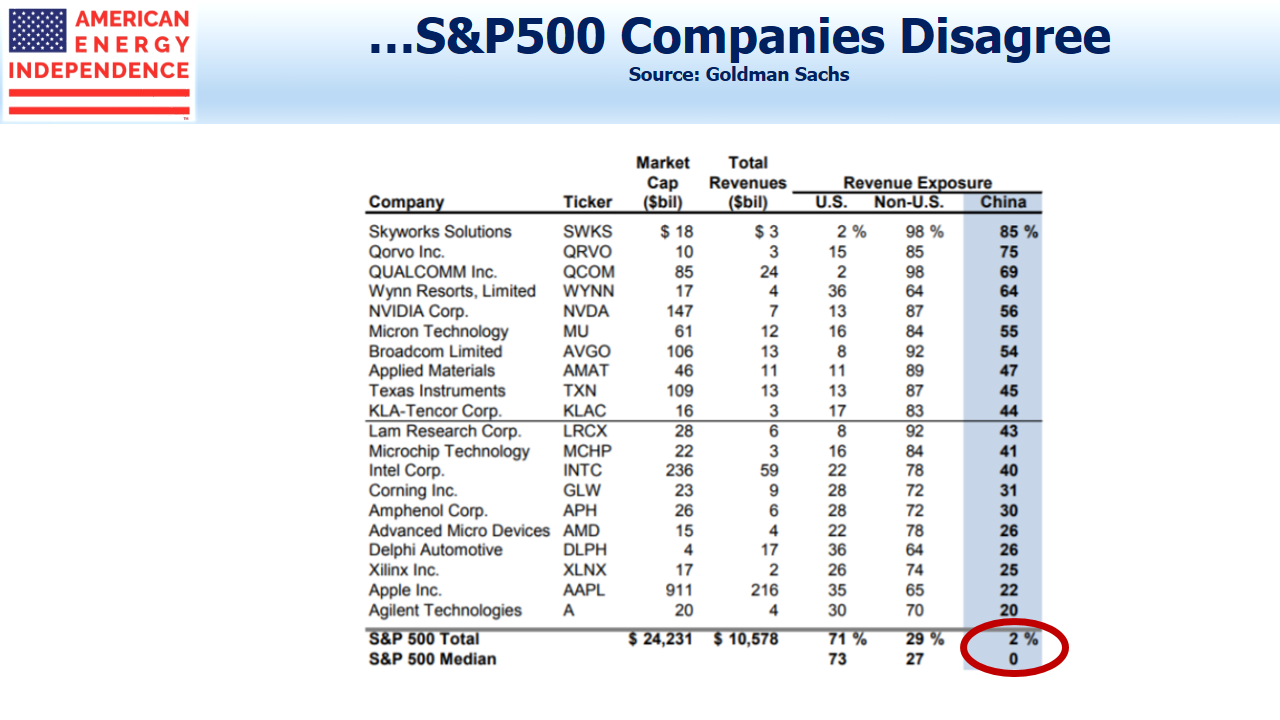

Almost every company in the S&P 500 does business in China and other emerging economies. They are infinitely better suited to allocate their capital where returns are highest. They’re far better equipped to protect their property and future cashflows from nefarious activity. This means that an investment in a broad portfolio of U.S. stocks includes exposure to the growth of emerging economies. And the portion of that portfolio’s overall EM exposure is the aggregate of hundreds of capital allocation decisions by the senior executives of those companies.

Blackrock published a paper last year suggesting that China’s 8% global weighting should drive an investor’s China allocation. But this seems too simplistic. The S&P 500 derives 2% of its revenues from China. 500 management teams from America’s biggest companies have collectively arrived at 2% as the optimal exposure. An investor who deviates from this 2% figure needs a good reason. Size of market is not one of them, because Jason Zweig’s article shows that most of the growth in China’s equity market cap has come from new issuance, not appreciation. Blackrock’s suggestion ignores the conclusion of hundreds of companies doing business there that have settled on 2%. And when they collectively decide to go to 3%, your exposure will change without you having to think too hard about it.

Relying on the S&P 500 to determine your EM exposure must surely be better than simplistically relying on market cap or trying to figure it out yourself. Simple can be better, and in investing it usually is. Invest in America’s global companies. Let them allocate to EM for you. Stay away from EM funds. You’ll sleep better, and the research shows you’ll get better results too.